McCune–Albright Syndrome

Clinical Definition and Characteristics

The McCune–Albright syndrome, also known as polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, is a rare genetic disease characterized by the clinical triad of

- polyostotic fibrous dysplasia affecting the bones; thus resulting in fractures, deformities, and X-ray abnormalies,

- multiple areas of skin pigmentation which are light brown birthmark or café-au-lait spots, and

- autonomous hyperfunction of one or more endocrine glands, especially gonads and thyroids.

The syndrome was delineated by McCune and Bruch in 1936 and 1937 and by Albright et al in 1937 and 1938, although it was described as early as 1922 by Weil.

At least two of the characteristic features must be present to consider the diagnosis. Other endocrinopathies include

- hyperthyroidism,

- adrenal nodules with Cushing’s syndrome,

- hyperprolactinaemia,

- acromegaly, and

- hyperparathyroidism.

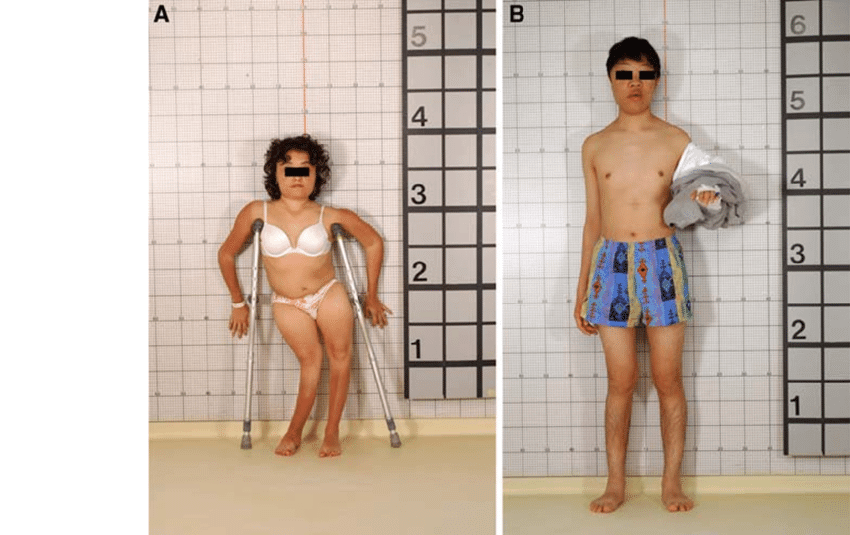

Figure X-1 | Presentation courtesy of ResearchGate Opens in new window

Figure X-1 | Presentation courtesy of ResearchGate Opens in new window

|

| The varied phenotype of two patients with McCune–Albright syndrome. The patient depicted in 'A' has had premature closure of the physes from precocious puberty, and that, together with lower extremity bowing (windswept deformity), has resulted in short stature. The patient in 'B' has acromegaly Opens in new window in addition to precocious puberty, thus the presence of growth hormone “rescued” him from short stature. |

Hypophosphataemic hyperphophaturic rickets may also be present.

Rarely, severely affected patients may present with hepatic and gastrointestinal dysfunction (e.g. hepatobiliary disease, pancreatitis, gastrointestinal polyposis), cardiac arrhythmias, and aortic root dilatation.

Epidemiology

The estimated prevalence of McCune–Albright syndrome ranges between 1/100,000 and 1/1,000,000. Most commonly, it is found in early childhood but severe cases have also been reported in infancy.

Both sexes can be affected, but the syndrome is more common and occurs earlier in girls. Menstrual periods usually begin in early childhood, long before the appearance of breast buds or pubic hair development.

Pathophysiology

The syndrome is caused by a postzygotic somatic mutation in the GNAS-1 gene that is sporadic rather than inherited. The GNAS-1 gene encodes for the Gsα (guanine-nucleotide binding) protein.

The substitution of arginine into histidine or cysteine results in continuous overactivity of the adenylate cyclase system and unregulated productivity from affected tissues. The abnormalities associated with this syndrome are related to this overacitivity.

McCune–Albrght syndrome results in mosaicism Opens in new window, such that the abnormal gene Opens in new window is present in only a fraction of the patient’s cells.

The timing of the mutation determines which organ systems are affected and the severity of the presentation, thus explaining the heterogeneity of these syndromes.

Clinical Manifestations

- Skeletal manifestation

Although any bone may be involved, the long bones are most frequently affected, especially the upper end of the femur Opens in new window.

Bowing Opens in new window resembling a hocky stick may be produced, resulting in leg-length discrepancy. Limp, leg pain, or fracture is the presenting complaint in about 70%.

Other bones affected, in descending order of frequency, are the tibia, fibula, pelvis, humerus, radius, and ulna. Bilateral involvement occurs in about half the cases.

Occasionally, a single bone is involved. Incipient bowing of the legs may be seen as early as the first year of life and nearly always appears before the end of the first decade. The process may be asymptomatic or accompanied by pain and fracture.

Fractures may be multiple and recurrent. At least 85% have one fracture, and over 40% have three or more. Occasionally, bones on only one side of the body may be involved. Scintigraphic studies have been reported.

Bone is replaced by a yellowish to red-brown fibrous tissue, its composition varying greatly in different parts of the body. It may be rich or poor in cells.

The stroma may vary from a finely fibrillar one with a loose whorled arrangement to one that is densely collagenous.

Some areas appear edematous, with numerous small cystic spaces. Foci of hemorrhage and multinucleated giant cells may be observed.

The trabeculae Opens in new window are irregular in form, and occasionally a few fragments of cartilage are present. Facial asymmetry occurs in about 25% and be accompanied by protrusion of an eye with associated visual disturbances in some instances.

The bony lesions of the skull and facial skeleton, in contrast to the cystic lesions of long bones, are hyperostotic. The skull base becomes thickened and dense, bulging upward into the cranial cavity.

The calvaria may also become thickened, with marked occipital and frontal bulging. Bossing Opens in new window may be asymmetric, with unilateral, and occasionally bilateral, obliteration of the sinuses and nasal passages.

Overgrowth of bone around foramina may result in deafness and blindness. Furin et al repored an intracranial frontoethmoid mucocele.

The jaws may be enlarged, expanded, and distorted. Radiographic examination may show a dense mass, especially in the maxilla, extending into and obliterating the sinuses and expanding the buccal plate in the tuberosity areas, or there may be a radiolucent area, more common in the mandible, similar to that seen in long bones.

Often there is loss of trabeculae and “ground-glass” appearance on radiographic examination.

- Cutaneous manifestation

Skin pigmentation in McCune–Albright syndrome is the café-au-lait type Opens in new window; and is the most common clinical sign. Well-defined, generally unilateral, irregular macular spots are scattered over the forehead, nuchal area Opens in new window, and buttocks.

Only rarely is the face, lips, or mucosa affected. They are usually present in infancy and become more prominent with advancing age. Their borders are irregular (‘coast of Maine’) and their color ranges from light to dark brown.

Pigmented areas do not have a segmented distribution, do not cross the midline, and there appears to be a correlation between the amount of pigmentation and the degree of bone involvement.

It has been stated that pigmentation is more frequent on the side of unilateral bone involvement, although this has been denied.

The pigmentation appears from the fourth month to the second year of life. In a few patients, it has become evident a few weeks postnatally. In one patient, symptoms resembling epidermal nevus syndrome were found.

- Endocrine manifestations

Endocrine abnormalities in this syndrome are characterized by autonomous hyperfunction.

In affected patients, any given endocrine gland may function normally. At autopsy, characteristic endocrine nodular hyperplasia may be found that did not give rise to clinical signs of hyperfunction during life.

In fact, endocrine organs, in spite of autonomy, may function so nearly normally that their independence is not recognized until appropriate tests have been performed.

Precocious puberty Opens in new window (of sexual precosity) is the most common endocrine manifestation, especially in females. It generally manifest earlier in girls than in boys and is heralded by irregular vaginal bleeding due to excess oestrogen production from ovarian follicular cysts.

Menarche Opens in new window is reached between 1 and 5 years of age in 50% and between 6 and 10 years in another 33% of patients. However, vaginal bleeding may occur within the first few months of even the first few days of life. Again, it is usually irregular, lasts from 2 to 4 days, and may, on occasion, be profuse.

Breast development and pubic and axillary hair appear after menarche, usually from the fifth to the tenth year, but may be manifest as early as birth.

Hypertrophy Opens in new window of the internal and external genitalia occurs. It is remarkable that affected women can be fertile.

In males with sexual precocity Opens in new window, enlargement of the penis and testes is accompanied by growth of pubic hair, suggesting hyperfunction Opens in new window (or overactivity) of both spermatic tubules and Leydig cells Opens in new window.

Precocious puberty in males may be accompanied by gynecomastia Opens in new window. Acromegaly Opens in new window or gigantism Opens in new window has also been described.

Hyperthyroidism Opens in new window is present in about 20%, occurring at an early age. The sex distribution is approximately equal. Thyrotoxic manifestations such as irritability, poor weight gain, and growth failure have been described during infancy, as early as 3 months in one instance.

With untreated sexual precocity or hyperthyroidism, skeletal maturation is often rapid and premature closure of the epiphyses may result, producing short stature in adulthood.

Various other endocrine disorders have also been documented, including Cushing’s syndrome Opens in new window, hypersomatotropinism, hyperprolactinemia, hyperparathyroidism, throid storms after surgery, and hypophosphatemic vitamin D–resistant rickets or osteomalacia without hypercalcemia or elevated parathyroid hormone levels.

Other clinical complications

- Central nervous system

Although the overwhelming majority of patients have normal intelligence, mental deficiency has been reported in a few instances. It may be secondary to factors such as prematurity, hypercorticalism, or grossly malformed skull.

The significance of mental retardation Opens in new window in others remain unclear. In the original description of Albright et al, an accessory mammillary body was found at autopsy. However, no other patient has exhibited this finding.

- Neoplasms

Malignancies are rarely described. The most unusual malignancy recorded to date has been carcinoma of the breast Opens in new window in an 11-year old girl. Endometrial carcinoma and maxillary osteosarcoma have also been recorded. Instances of sarcoma Opens in new window arising in areas of fibrous dysplasia have been secondary to radiation therapy.

Other neoplasms have been observed in patients with isolated polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, but could conceivably occur as components of McCune–Albright syndrome.

Multiple intramuscular myxomas have been noted in a number of such patients. This is known as mazabraud syndrome Opens in new window and may be associated with osteogenic sarcoma.

Reticuloendothelial hyperplasia with lymphoid and myeloid metaplasia has been described. Leukemia, osteoma of the skin, osteosarcoma, and meningioma have also been noted.

Differential Diagnosis

Fibrous dysplasia may occur without McCune–Albright syndrome. The overwhelming majority of cases are monostotic; polyostotic involvement occurs much less frequently and, of these, only 3% have McCune–Albright syndrome.

Radiographically, bone lesions should be distinguished from those of hyperparathyroidism, histiocytosis X, multiple myeloma, Paget disease of bone, neurofibromatosis, and giant cell tumor.

Skin pigmentation is also seen in neurofibromatosis Opens in new window. “Coast of California” contour is typical of neurofibromatosis and a markedly irregular outline (“Coast of Maine”) usually occurs with McCune–Albright syndrome; exceptions have been noted.

Giant pigment granules, characteristically seen in malpighian cells or melanocytes in neurofibromatosis, are very rare in McCune-Albright syndrome. Precocious puberty occurs in the adrenogenital syndrome, with ovarian granulose cell tumor, and occasionally in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.

Therapeutics

McCune–Albright syndrome is a multisystem disease, and its treatment depends on clinical presentation. Precocious puberty is gonadotrophin independent and does not respond to GnRH agonists.

Aromatase inhibitors are the drugs most commonly used, since the man purpose is to block oestrogen effects. Letrozole, a third-generation aromatase inhibitor, has been shown to be effective.

The oestrogen-receptor modulator tamoxifen has shown promising results, and a recent study revealed moderate effectiveness of the oestrogen receptor antagonist fulvestrant in girls presenting with the syndrome.

Additional treatment options include cyproterone acetate and medroxyprogesterone acetate, whilst male patients are typically treated with a combination of spironalctone and aromatase inhibitors.

There is no established treatment for fibrous dysplasia. Bisphosphonates are frequently used, mostly for pain relief and/or pathologic fracture prevention, but they have no effect on the evolution of bone disease.

Surgical intervention is indicated for the treatment of fractures or severe painful malformations. Radiation therapy should be avoided because it is associated with high risk for malignant transformation.

If Cushing’s syndrome does not resove spontaneously, bilateral adrenalectomy is the treatment of choice.

Growth-hormone excess is treated with pharmacotherapeutic agents such as long-acting somatostatin analogues or pegvisomant. Dopamine agonists may be necessary if prolactin is also secreted from the tumor.

See also:

- Abs R et al: Acromegaly, multinodular goiter and silent polyostotic fibrous dysplasia. A variant of McCune-Albright syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest 13:671-675, 1990.

- Albright F et al.: Syndrome characterized by osteitis fibrosa disseminate; areas of pigmentation and endocrine dysfunction with precocious puberty in females. N Engl J Med 216:727-736, 1937.

- Albright F et al: Syndrome characterized by osteitis fibrosa disseminate, areas of pigmentation and a gonadal dysfunction. Endocrinology 22:411-421, 1938.

- Alvarez-Arratia MC et al: A probable monogenic form of polyostotic fibrous dysplasia. Clin Genet 24:132-139, 1983.

- Bianco P et al: Mutations of the GNAS1 gene, stromal cell dysfunction, and osteomalacic changes in non-McCune-Albright fibrous dysplasia of bone. J Bone Miner Res 15:120-128, 2000.

- Bercaw-Pratt JL, Moorjani TP, Santos XM, et al. Diagnosis and management of precocious puberty in atypical presentations of McCune-Albright syndrome: A case series review. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2012; 25: e9-13.

- Collins MT, Singer FR, and Eugster E. McCune-Albright syndrome and the extraskeletal manifestations of fibrous dysplasia. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2012; 7: S4.

- Collins MT. Spectrum and natural history of fibrous dysplasia of bone. J Bone Miner Res 2006; 21:99-104.

- De Sanctis C, Lala R, Matarazzo P, et al. McCune-Albright syndrome: A longitudinal clinical study of 32 patients. J Pediatr Endocrinal Metab 1999; 12: 817-26.

- Diaz A, Dancon M, and Crawford J. McCune-Albright syndrome and disorders due to activating mutations of GNAS1. J Pediatr Endocrinal Metab 2007;20: 853-80.

- Dumitrescu CE and Collins MT. McCune-Albright syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2008;3:12.

- Eugster EA, Rubin SD, Reiter EO, et al. Tamoxifen treatment for precocious puberty in McCune-Albright syndrome: A multicentre trial. J Paedatr 2003;143: 60-6.

- Danon M, Crawford JD: The McCune-Albright syndrome. Ergeb Inn Med Kinderheilkd 55:82-115, 1987.

- De Sanctis M et al: McCune-Albright syndrome: A longitudinal clinical study of 32 patients. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 12:817-826, 1999.

- Pfeffer S et al: McCune-Albright syndrome: The patterns of scintigraphic abnormalities. J Nucl Med 31:1474-1478. 1990.

- Happle R: The McCune-Albrght syndrome: A lethal gene surviving by mosaicism. Clin Genet 29:321-324, 1986.

- Feullan P, Calis K, Hill S, et al. Letrozole treatment of precocious puberty in girls with the McCune-Albright Syndrome: A pilot study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007; 92:2100-6.

- Gaujoux S, Salenave S, Ronot M, et al. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic neoplasms in patients with McCune-Albright syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014; 99:E97-101.

- Ippolito E, Bray EW, Corsi A, et al. Natural history and treatment of fibrous dysplasia of bone: A multicenter clinicopathologic study promoted by the European Pediatric Orthopaedic Society. J Pediatr Orthop B 2003, 12:155-77.

- Sims EK, Garnett S, Guzman F, et al. Fulvestrant treatment of precocious puberty in girls with McCune-Albright syndrome. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol 2012; 2012: 26.