Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Definition and Introduction

|

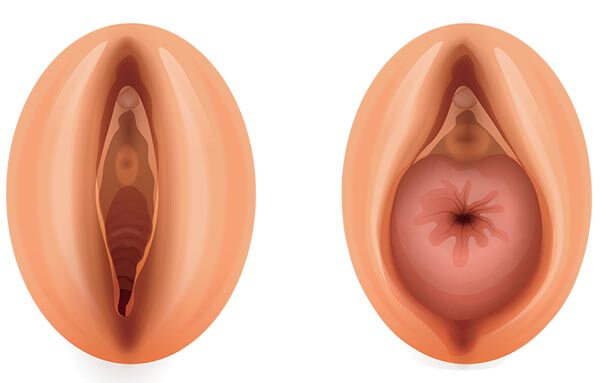

| Image courtesy of Bella Donna Medical Opens in new window Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is a condition that happens when the muscles and tissues supporting the pelvic organs (the uterus, bladder, or rectum) weaken or relax. When they become too relaxed, one or more of the pelvic organs drop down and press against or bulge into the vagina (as clearly shown in the image above). |

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is a common condition with a significant deleterious impact on quality of life. This condition is more commonly seen in the elderly population, affecting 37% of women over the age of 80.

There are several factors involved in the etiopathogenesis. Age related vascular changes impair circulation to tissue and combined with the decreased elasticity of collagen with age, the older woman is at increased risk of POP. Loss of vaginal rugae becomes apparent 2–3 years after the menopause. This occurs secondary to increased collagen breakdown which is considered to be a factor in the etiology of POP.

The lifetime risk of undergoing surgery to treat POP is 11%. Currently 33% of neonates survive until the age of 80 years. It has been predicted this will rise to 50% by 2050. As the life expectancy of women is greater than that of men, the proportion of women in the elderly population will increase even further.

Surgery for POP accounts for approximately 20% of elective major gynaecological surgery and this increases to 59% in elderly women. By 2030, there will be approximately 39.9 million women in this age group, with a ratio of growth almost double that of the general population.

Overall, individuals aged 65 years and older will represent 19% of the population by 2030, compared with 12.4% of the population in 2000. In addition, women more than 80 years of age are the fastest growing segment of society. As both the incidence and prevalence of prolapse surgery increase with age, pelvic organ prolapse (POP) becomes an increasingly bothersome disorder in this patient population.

The management of POP is symptom driven, therefore, if POP does not cause significant bother it rarely needs active intervention. Exception obviously exist, for example, if a prolapse has become ulcerated, management is required to prevent infections and severe sequelae. A procidentia can cause renal dysfunction secondary to kinking off the ureters.

Review by a specialist with the aid of a validated quality of life questionnaire such as the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire — Vaginal Symptoms (ICIQ-VS) is essential. These assessment tools will help assess bother, as well as the frequency and severity of urinary, bowel and sexual symptoms.

Treatment

Surgery remains the definitive treatment of POP. Age itself is not a contraindication to any type of anesthesia. The sensitivity to drugs increases with age whilst metabolism and clearance of drugs decreases with age. The effect of aging on the cardiovascular, respiratory, immune and clotting systems increases the risks of intra- and post-operative morbidity.

The mean overall complication rate for POP surgery is 3.8% with cardiovascular events the most common. Almost 6% of women suffer short-term urinary retention requiring catheterization. Catheterization may increase the likelihood of decreased mobility, venous thromboembolism and urinary tract infection (UTI).

UTIs are a common cause of temporospatial disorientation which occurs in 4.6% of older women post POP surgery. The objective success rate in women over 75 years of age was 87.6%, however highlighting the viability of surgery for POP in the elderly. There was no difference in POP treatment failure rates in women who were 65 years of age or more when compared to women under 65. Administration of low dose vaginal oestrogen after POP surgery via an estradiol-releasing ring is feasible and results in improved markers of tissue quality postoperatively compared to placebo and controls.

Surgical repair of POP depends on the compartment which is affected. The exact operation which is performed is determined by a number of factors including patient preference, sexual activity, isolated vault prolapse, multiple previous surgeries, concomitant intra-abdominal pathology, co-existing lower urinary tract symptoms, and planned staged procedure.

The commonest route used to repair POP is transvaginal. Other routes include transanal/perineal, abdominal, laparoscopic and robotic. There are no high quality clinical trials to guide the operating surgeon regarding the best operation.

In patients with recurrent prolapse, one may consider repeat surgery with native tissue, repeat surgery with mesh augmentation or colpocleisis. Both the latter require a fully informed detailed consultation with the patient in view of the increased risks or cessation of sexual activity, respectively.

POP repair with mesh augmentation compared to using native tissue only has been shown to reduce the recurrence of POP by up to 30% but has a significantly higher serious complication rate. (Cochrane) Complications include prominence, exposure or extrusion of the mesh, alongside the formation of fistulous tracts. This can lead to vaginal bleeding, vaginal discomfort, dyspareunia, lower urinary tract or even bowel symptoms. Colpocleisis is the surgical closure of the vagina up to the introitus. This relieves symptoms of prolapse but precludes sexual intercourse.

Patients suffering from stress incontinence together with POP may consider the benefits of concomitant insertion of a mid-urethal sling such as the tension free vaginal tape (TVT) at the same time as the POP repair. There has been a large body of evidence supporting this practice. For some women, reduction of the prolapse may expose underlying ‘occult’ stress incontinence. Pre-operative urodynamics may highlight this and as long as the patient is fully counseled, they may wish to be managed with either an interval or concomitant procedure.

- Pelvic organ prolapse is more common in elderly patients.

- The commonest symptom is vaginal bulge (bulge sensation or the sensation of something coming down through the vaginal introitus).

- Diagnosis can be confirmed with vaginal examination to identify the presence, compartments affected, extent and potential complications of POP.

- Different treatment options are available, including observation, lifestyle management, physiotherapy and use of pessaries, as well as surgical options.

- Management should be tailored on an individual basis, based on symptoms, desire for treatment and comorbidity.

- Pessaries and colpocleisis are the treatment options used more often in elderly patients than in the general population.

Focal Points

- Adapted from: Pelvic Floor Dysfunction and Pelvic Surgery in the Elderly: An Integrated ... Authored By David A. Gordon, Mark R. Katlic. References as cited include:

- Morley GW. Treatment of uterine and vaginal prolapse. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1996; 39(4):959–69.

- Gosain A, DiPietro LA. Aging and wound healing. World J Surg. 2004;28(3):321–6.

- Sturdee DW, Panay N. Recommendations for the management of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy. Climacteric, 2010; 13:509–22.

- Philips CH, Anthony F, Benyon C, et al. Collagen metabolism in the uterosacral ligaments and vaginal skin of women with uterine prolapse. BJOG. 2006;113:39–46.

- Moalli PA, Talarico LC, Sung VW, et al. Impact of menopause on collagen subtypes in the arcus tendineous fasciae pelvis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:620–7.

- Tinelli A, Malvasi A, Rahimi S, et al. Age-related pelvic floor modifications and prolapse risk factors in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2010;17:204–12.

- Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, et al. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89(4):501–6.

- Mathers CD, Murray CJL., Lopez AD, et al. Global patterns of healthy life expectancy for older women. J Women Aging. 2002;14(1–2):99–117.

- Silva EA, Kleeman S, Segal J, et al. Effects of a full bladder and patient positioning on pelvic organ prolapse assessment. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(1):37–41.

- Visco AG, Wei JT, McClure LA, et al. Effects of examination technique modifications on pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POP-Q) results. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2003;14(2):136–40.

- Barber MD, Lambers A, Visco AG, et al. Effects of patient position on clinical evaluation of pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(1):18–22.

- Miedel A, Tegerstedt G, Maehle-Schmidt M, et al. Nonobsteric risk factors for symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(5):1089–97.

- Lang JH, Zhu L, Sun ZJ, et al. Estrogen levels and estrogen receptors in patients with stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;80(1):35–9.