Prader-Willi Syndrome

Photo source: The Internet

Photo source: The Internet

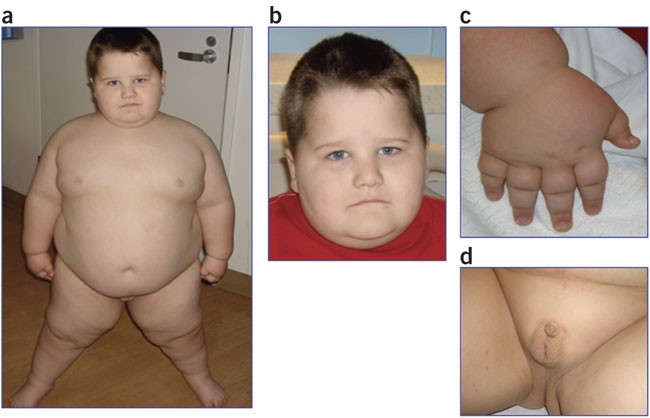

Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) is a genetic neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by hypotonia and failure to thrive in infancy, progressing to developmental delay, short stature, rapid weight gain and obesity due to hyperphagia (excessive appetite), and intellectual disability. |

Prader-Willi syndrome is characterized by developmental abnormalities that include severe hypotonia with poor suckling, and feeding difficulties in early infancy, delay in motor and language progression, some degree of cognitive disability, stubbornness, and manipulative and compulsive behaviors.

PWS affects approximately 1 in 10,000 – 30,000 individuals. The disorder is a result of the absence of paternally expressed genes at the level of the 15q11,2-q13 chromosomal region. Frequently this is because of the paternal deletion of this region (up to 75% of affected subjects).

Maternal uniparental disomy, or imprinting defects, translocations, and microdeletions may also occur. virtually all affected patients may be detected by parent-specific DNA methylation analysis. Interestingly, the loss of a nucleolar organizing RNA gene, SNORD 116, has been shown as related to hyperphagia and obesity in PWS.

| Table X-1. Major and minor clinical manifestations of Prader Willi syndrome | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | Major characteristics | Minor characteristics |

| Birth to 2 y |

|

|

| 2 y – 6y |

|

|

| 12 y-adulthood |

|

|

- HypogonadismOpens in new window may be present at birth in boys with cryptorchidism, scrotal hypoplasia, and small penis, and in girls with poor development of the labia minora and clitoris.

- Incomplete, delayed, or very rarely precocious puberty occurs.

- Low sex steroid hormones and gonadotropins with blunted response to GnRH and (not invariably) infertility are observed.

- Short stature is common, related to growth hormone treatment (Table X-1).

Characteristic facial features with a narrow bitemporal diameter, almond-shaped eyes, palpebral fissures, and down-turned mouth, strabismus, and scoliosis are often present, and there is an increased incidence of sleep disturbances.

Type 2 diabetes mellitusOpens in new window is frequent particularly in obese subjects and occurs at young age (mean age of onset around 20 years). HypertensionOpens in new window occurs in up to 38% in adults but it is uncommon in children. Increased risk of death in adults with PWS is related to the cardiorespiratory complications of obesity such as cardiac or respiratory failure and obstructive and central apnea.

Severe infections, skin or respiratory, are also causes of death. Unsupervised and rapid ingestion of large amounts of food have been related to increased risk of choking and gastric damage. Sleep disturbances and abnormalities in temperature control and heat generation may be part of the hypothalamic syndrome in these patients.

SPECTOpens in new window and PETOpens in new window findings suggest hypoperfusion of several brain regions in PWS (left insula, anterior cingulum, and superior temporal regions), which appear to correlate with behavioral and psychosocial disturbances in these patients.

Nutritionally, subjects with PWS progress from birth through seven different nutritional phases. Initially, the infant is not obese, and has feeding difficulties with failure to thrive.

Beginning at about 2 years of age, the weight increases initiatlly without a significant change in appetite or caloric intake, and afterward (4 to 5 years of age), weight gain is associated with a concomitantly increased interest in food with hoarding or foraging for food, eating of inedibles and from garbage, and stealing of food or money to buy food.

Encountered in PWS are delayed meal termination, lack of satiety, early return of hunger after the previous meal with early meal initiation, and approximately threefold more food ingestion than in controls, all resulting in weight gain during a short period of time. Obesity results from these behaviors and from decreased total caloric expenditure (reduced physical exercise because of obesitiy, hypersomnolence, persistent poor muscle tone, and low lean body mass), which appears to be tightly linked to the genetical profile of PWS.

Obesity in PWS is primarily central in both sexes, and increase in both subcutaneous and visceral fat is observed, although this latter is relatively well controlled by growth hormone treatment.

Ghrelin, an orexigenic stomach-derived hormone, is elevated in hyperphagic older children and adults with PWS but whether or not this increase may be observed even before development of obesity and hyperphagia is controversial.

Early initiation of an energy-restricted diet with a well-balanced macronutrient composition and fiber intake, psychological and behavioral counseling of patient and family, and appropriate exercise regimens are the mainstay of obesity treatment in PWS.

GLP-1 agonists exenatide and liraglutide have been proposed for the treatment of diabetes in PWS but their chronic use may be limited by their delaying effect on gastric emptying. In selected cases bariatric surgery can be considered.

Growth hormone therapy helps to reduce fat mass and to increase muscle mass without altering hyperphagia in both children and adults. Recent guidelines recommend that growth hormone treatment should be considred for pediatric and adult patients with genetically confirmed PWS together with lifestyle interventions after a multidisciplinary expert evaluation that includes biochemical growth hormone dynamic testing.

See also:

- Holm VA, Cassidy SB, Butler MG, et al. Prader-Willi syndrome: consensus diagnostic criteria. Pediatrics 1993;91(2):398 – 402.

- Gunay-Aygun M, Schwartz S, Heeger S, et al. The changing purpose of Prader-Willi syndrome clinical diagnostic criteria and proposed revised criteria. Pediatrics 2001; 108(5):E92.

- Haqq Am, Grambow SC, Muehlbauer M, et al. Ghrelin concentrations in Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) infants and children: changes during development. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;69(6):911 – 20.