Conscious & Unconscious Experiences

What is Consciousness?

The words consciousness, conscious mind and awareness are used very freely in psychiatry but often without a precise meaning.

To be in the state of consciousness is to be in the experiential condition of being aware of the World. As it is often said of the conscious, they are ‘in touch’ with Reality as those lost in a trance or dream are not.

- Consciousness ‘is a state of awareness of the self and the environment’ (Fish, 1967);

- also, consciousness ‘is to be conscious, to know about oneself and the world’ (Scharfetter, 1980);

- and, ‘by consciousness, implies those subjective states of sentience or awareness that end when one goes to sleep at night or falls into a trance, coma, or dies, or otherwise becomes as one would say, unconscious’ (Searle, 1994).

Clinically consciousness denotes:

- first of all actual inner awareness of experience (as contrasted with the externality of events that are the subject of biological inquiry);

- secondly, it denotes a subject-object dichotomy (i.e., a subject intentionally directs itself to objects which it perceives, imagines or thinks);

- thirdly, it denotes the knowledge of a conscious self (self-awareness).

The field of clear consciousness within the total conscious state is termed the field of attention. This covers three closely connected but conceptually distinct phenomena:

- attention as experience of turning oneself towards an object

- the degree of attention, i.e., degree of clarity and distinctness of the conscious content

- the effects of these two phenomena on the further course of psychic life (as e.g., rousing further associations).

What then is Unconsciousness?

Unconscious, according to Jaspers (1959),

- ‘means firstly something that is not an inner existence and does not occur as an experience;

- secondly, something that is not thought of as an object and has gone unregarded;

- thirdly, it is something which has not reached any knowledge of itself.’

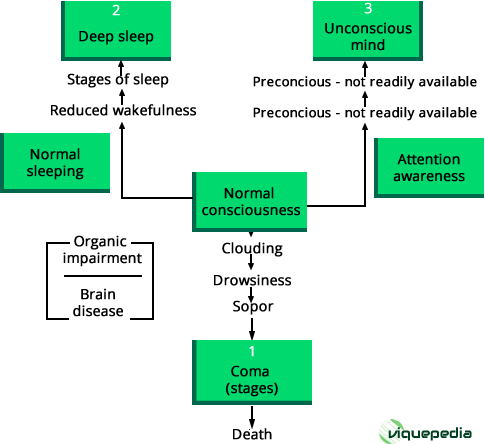

In clinical practice, the term unconscious is used in three quite different ways that have in common only the phenomenological element in that there is no subjective experience (Figure X-1):

- A person suffering from serious brain disease may be unconscious; consciousness in this instance is seen as being on a continuum, with a normal state of consciousness at one end and death at the other.

- Someone who is asleep is unconscious; again, there is continuum from full wakefulness to deep sleep.

- An alert and healthy person is aware of only certain parts of his environment both externally and internally; of the rest, he is unconscious. There is also a continuum here from full vigilance directed towards the immediate object of awareness to total unawareness.

Figure X-1. Three levels of unconsciousness

Figure X-1. Three levels of unconsciousness

The organic state of the brain as, for instance, demonstrated by the electroencephalogram is utterly different in these three situations.

The third meaning of unconsciousness implies that certain mental processes cannot be observed by introspection alone, even when the brain is normal and healthy. Among such processes, for which there is good evidence of their existence, frequency and complexity, there are some that have been, or may yet become, conscious. This is what Freud called the preconscious (Frith, 1979).

Whereas there is a strict limit to the number of items available in the conscious state and that are therefore capable of being memorized (approximately seven, for example a number with seven digits), there is very much more information stored at the preconcious level.

If a stimulus is ambiguous, only one interpretation is possible in consciousness at any one time; however, multiple meanings are available preconsciously. It is very difficult to carry out more than one task at a time consciously, but undertaking parallel tasks is usual at a preconscious level.

Preconscious processes are automatic, whereas conscious ones are flexible and strategic. This function of the preconscious was well known long before Freud, for example Brodie (1854):

But it seems to me that on some occasions a still more remarkable process takes place in the mind, which is even more independent of volition than that of which we are speaking; as if there were in the mind a principle of order which operates without our being at the time conscious of it. It has often happened to me to have been occupied by a particular subject of inquiry; to have accumulated a store of facts connected with it; but to have been able to proceed no further. Then, after an interval of time, without any addition to my stock of knowledge, I have found the obscurity and confusion, in which the subject was originally enveloped, to have cleared away; the facts have all seemed to have settled themselves in their right places, and their mutual relations to have become apparent, although I have not been sensible of having made any distinct effort for the purpose.

Dimensions of Consciousness

Consciousness, then, is the awareness of experience. There may be awareness of objects or self-reflection.

- Awareness of objects includes the capacity to be aware of onself as an object;

- self-reflection refers to the subjective experiencing of self.

The three dimensions of consciousness (contrasted with unconsciousness, as shown in Figure X-1 ) are vigilance, lucidity and self-consciousness.

- Vigilance (wakefulness)-drowsiness (sleep)

Vigilance is taken to mean the faculty of deliberately remaining alert when otherwise one might be drowsy or asleep. This is not a uniform or unvarying state, but it fluctuates.

Factors inside the individual that promote vigilance are interest, anxiety, extreme fear or enjoyment, whereas boredom Opens in new window encourages drowsiness.

The situation in the environment and the way the individual perceives that situation also affect the vigilance-drowsiness axis. Some abnormal states of health increase vigilance, while many diminish it.

As well as the contrast between vigilance and drowsiness, there are qualitative differences in the nature of wakefulness. The vigilant state of mind of a person scanning a radar screen for a possible enemy interceptor is very different from the rapt attention of a music lover listening to a symphony.

- Lucidity-Clouding

Consciousness is inseparable from the object of conscious attention: lucidity can be demonstrated only in clarity of thought on a particular topic.

The sensorium, the total awareness of all internal and external sensations presenting themselves to the organism at this particular moment, may be clear or clouded. Obviously, lucidity is not unrelated to vigilance: unless the person is fully awake, he cannot be clear in consciousness.

Clouding of consciousness denotes the lesser stages of impairment of consciousness on a continuum from full alertness and awareness to coma (Lishman, 1997).

The patient may be drowsy or agitated and is likely to show memory disturbance and disorientation.

In clouding, most intellectual functions are impaired, including attention and concentration, comprehension and recognition, understanding, forming associations, logical judgment, communication by speech and purposeful action.

- Consciousness of self

Alongside full wakefulness and clear awareness is an ability to experience self, and an awareness of self, that is both immediate and complex.

You Might Also Like:

- Adapted from:

- Sims' Symptoms in the Mind: An Introduction to Descriptive Psychopathology By Femi Oyebode

- Crash Course Psychiatry - E-Book By Katie FM Marwick, Steven Birrell