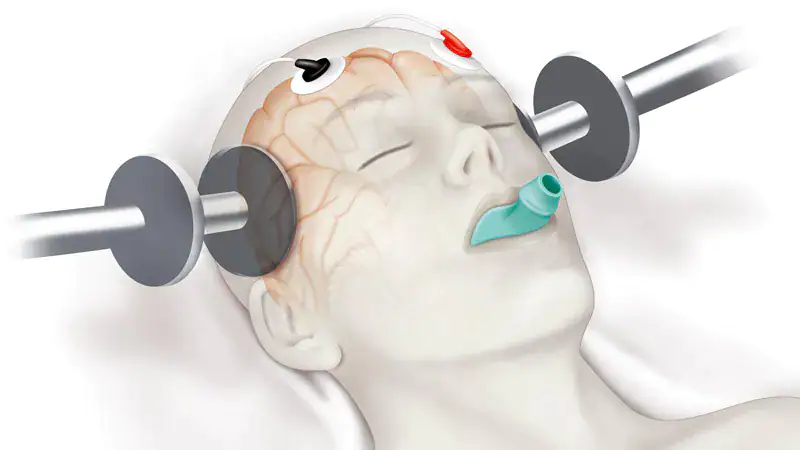

Electroconvulsive Therapy

Graphical diagram courtesy of MedscapeOpens in new window

Graphical diagram courtesy of MedscapeOpens in new window

|

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a psychiatric treatment that involves passing electrical current through the brain to induce an epileptic seizureOpens in new window. It is currently used to treat severe, refractory (treatment resistant) depression. ECT has also been used to treat schizophreniaOpens in new window and bipolar disorderOpens in new window.

Before the development of ECT in the 1930s, treatment for severe mental illness consisted of restraint, seclusion, hydrotherapy (hoto and cold water therapy), sedation (with morphine, bromides, barbiturates, and chloral hydrate), surgical sterilization (hysterectomy or vasectomy), institutionalization, and other types of shock therapy.

In 1917, Austrian physician Julius Wagner-JaureggOpens in new window used malaria to induce fevers (pyrotherapy) to treat paralytic dementiaOpens in new window caused by syphilisOpens in new window (Fink, 1999).

In 1927, Austrian neurophysiologist and psychiatrist Manfred SakelOpens in new window used insulinOpens in new window to induce comas and convulsion to treat patients with schizophreniaOpens in new window or drug addiction.

Ladislas J. MedunaOpens in new window, a Hungarian neurologist and neuropathologist, studied glial cellsOpens in new window (neuroglia, or glia).

Glia are brain cells that maintain brain balance (homeostasis) and are part of brain signal transmission.

During autopsiesOpens in new window, Meduna found that the brains of patients with epilepsy had a higher than normal concentration of glia, while brains of patients with schizophrenia had lower than normal concentrations.

Meduna thought that inducing epileptic seizures in patients with schizophreniaOpens in new window might increase brain glia concentrations and relieve psychosisOpens in new window. Observations seemed to bear this out:

relatively few institutionalized schizophrenic patients had epilepsy, and those who developed seizures (after infection or head trauma) seemed to be relieved of their psychosis (Fink, 1999).

Meduna induced seizures using camphor oilOpens in new window and later using Metrazol (a heart medication). Ugo CerlettiOpens in new window, an Italian neurophysiologist, felt that Metrazol-induced seizures were useful in the treatment of schizophrenia but were too dangerous and difficult to control.

Cerletti had observed pigs being anesthetized with electroshock (inducing seizures) before being butchered. In 1938, Cerletti and Italian psychiatrist Lucio BiniOpens in new window developed a method using a brief electrical shock to induce seizures in humans (Fink, 1999).

Shock treatment became increasingly popular throughout the 1940s and early 1950s. Especially before the development of antidepressantsOpens in new window and antipsychotics in the 1950s, ECT was hailed as a modern and humane alternative to existing treatments for mental illness.

In the 1950s, ECT methods were improved through the use of anesthesia and muscle relaxants. This reduced the incidence of some of the side effects associated with earlier ECT methods such as tooth damage, broken bones, and joint dislocation.

Other side effects of ECT include risks associated with general anesthesiaOpens in new window, uncontrollable seizuresOpens in new window, peripheral nerve palsyOpens in new window, skin burns, short-term confusion following treatment, and retrograde or anterograde amnesiaOpens in new window (loss of memory of events before or after the ECT treatment).

Mental health practitioners, researchers, and patients disagree about the nature and extent of memory loss associated with ECT. ECT may be administered with electrodes placed on each temple (bilateral) or only on one temple (unilateral).

While bilateral treatment seems to be more effective than unilateral, it is also associated with more severe side effects, including more persistent memory loss. Likewise, ECT utilizing higher energy (greater voltage) seems to be more effective but also causes more impairment than low-energy ECT (Ebmeier, Donaghey, & Steele, 2006). ECT seems to be most effective for depression, especially with psychotic symptoms (delusions and hallucinations).

A course of ECT usually consists of a series of treatments given several times a week over a period of weeks or months. The effects of ECT are short-lived, so patients are likely to require pharmacologic (medication) follow-up treatment (Ebmeier et al., 2006).

There is a great deal of controversy about ECT. Issues include whether it is an effective treatment; disagreement about the nature, severity, and duration of side effects; patients satisfaction and perceptions about ECT; and issues of informed consent.

Opinions seem to be polarized, with some people extolling the benefits and effectiveness of ECT and others decrying side effects and a history of dangerous, abusive practices.

Patient reports about ECT differ from those of clinicians and researchers: mental health practitioners tend to report greater effectiveness and fewer side effects than do patients.

In a review of articles about patient views about ECT benefits and risks, at least one-third of patients reported persistent (long-term) memory loss (Rose, Fleischmann, Wykes, Leese, & Blindman, 2003). Reports of patient satisfaction with ECT vary; some estimates of patient satisfaction range from 30 to 80 percent (Barnes, 2009).

Issues of informed consent arise in situations when ECT is administered to the elderly, developmentally disabled individuals, or others who cannot truly understand the potential risks and benefits of ECT, either by virtue of lack of competence or because they are incarcerated.

Portrayals of ECT in the popular press have reflected attitudes, and helped to shape practices, surrounding ECT (Hirshbein & Sarvananda, 2008). The electric chair, introduced in the United States in the 1880s as a method of capital punishment, had been viewed as a sign of advancing civilization.

In a 1940 article in Science News Letter (Van de Water, 1940), ECT was hailed as a means to cure previously incurable diseases: “this new use of electricity for mental health instead of for death is being enthusiastically welcomed by the medical profession” (Hirshbein & Sarvananda, 2008, p. 3).

Portrayal of ECT in the 1975 film One Flew over the Cuckoo’s NestOpens in new window contributed to the perception of ECT as a tool of suppression and control or as a means to punish or manage unruly patients. This portrayal reflected a social climate in which questions were raised about patient rights, abuse, and psychiatry as a means of social control. In 1982, ECT was banned in Berkelye, California, by a voter-approved ballot initiative measure (which was later overturned).

Established therapies for severe depressionOpens in new window include antidepressant medicationOpens in new window and psychotherapy. Sometimes ECT is given in combination with other treatments (medication and/or psychotherapy). Other treatments being studied for severe depression include transcranial magnetic stimulation and vagus nerve stimulation.

- Dukakis, K., & Tye, L. (2006). Shock: The healing power of electroconvulsive therapy. New York: Penguin.

- Shorter, E., & Healy, D. (2007). Shock therapy: A history of electroconvulsive treatment in mental illness. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Fink, M. (1999). Electroshock: Restoring the mind. Cary, NC: Oxford University Press.

- Hirshbein, L., & Sarvananda, S. (2008). History, power, and electricity: American popular magazine accounts of electroconvulsive therapy, 1940 – 2005. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 44 (1), 1 – 18.

- Rose, D., Fleischmann, P., Wykes, T., Leese, M., & Bindman, J. (2003). Patients’ perspectives on electroconvulsive therapy: Systematic review. British Medical Journal, 326, 1363 – 1368.

- Van de Water, M. (1940, July 20). Electric shock, a new treatment to restore patients with hopeless mental disease. Science News Lettter, 38, 42 – 44.