Fecal Incontinence

1. Definition and Introduction

|

| Image courtesy of Bel Marra Health Opens in new window Fecal incontinence (FI) is defined as the recurrent, involuntary passage of liquid or solid stool (or as loss of voluntary control of stool elimination). FI is a common condition that results in significant physical and psychological disability. |

Fecal incontinence has also been defined as inadvertent passage of rectal contents, including soiling of underclothing or involuntary passage of gas, mucos, or liquid/solid stool.

Symptoms of FI includes the inability to hold a bowel movement until reaching a toilet as well as passing stool into one’s underwear without being aware of it happening.

Feces is solid waste that is passed as a bowel movement and includes undigested food, bacteria, mucus, and dead cells. Mucus is a clear liquid that coats and protects tissues in the digestive system.

FI is a challenging condition of diverse etiology and devastating psychological impact. It severely impacts on the quality of life of many sufferers and their families, often being given as the reason for admission to a care home. Therefore FI can be upsetting and embarrassing. Many people with FI feel ashamed and try to hide the problem. However, people with FI should not be afraid or embarrassed to talk with their health care provider. FI is often cause by a medical problem and treatment is available.

FI can be both emotionally and socially debilitating; thus the embarrassment associated with it is so great that it often prevents patients from seeking much needed help from their health care providers. Nursing care begins with case finding and continues through conservative management, which has greatly improved over the past 15 years.

2. Epidemiology

FI affects approximately 5% of the general population but its prevalence increases with age. Prevalence refers to the total number of patients with FI (as compared with the total population being studied) at a specific point in time. Nearly 70% of patients with FI have never discussed it with a physician. People of any age can have a bowel control problem, though FI is more common in older adults. Approximately 70% of institutionalized older adults have FI.

Obstetric injury is the primary reason for FI in women. Forty-three percent of women who undergo anal sphincter repair following birth still experience FI 12 weeks after surgery, and 11% report FI for as long as 18 months after surgery. FI is common among women with pelvic floor disorders; 20% of women affected by urinary incontinence have FI.

3. Risk Factors

FI has many causes, including; diarrhea or constipation, muscle damage or weakness, nerve damage or trauma, loss of stretch in the rectum, aging, congenital disorders, hemorrhoids and rectal prolapse, rectocele, inactivity.

Having any of the following can increase the risk:

- disease or injury that damages the nervous system;

- poor overall health from multiple chronic, or long lasting, illnesses,

- a difficult childbirth with injuries to the pelvic floor, the muscles, ligaments and tissues that supports the uterus, vagina, bladder, and rectum.

Apart from these there are many etiologic factors as shown in Table X.

| Etiological factors |

|---|

| Perianorectal trauma – Anal sphincter injury

|

| Abnormal anal sphincter or pelvic floor function – Rectal prolapse – Chronic straining |

| Neurologic disorders – Spinal cord – Brain injuries, strok and cerebrovascular disease – Myelomeningocele – Multiple sclerosis – Neuropathy (as may occur in diabetes, for example) |

| Loose stool consistency or bowel irritation or inflammation – Diarrhea

|

| Obstruction and overflow – Impaction – Neoplasms – Medications with antimotility adverse effects |

| Cognitive or functional disability – Dementia or delirium – Decreased mobility (resulting from stroke, arthritis, lower back problems or weakness) – Restraints – Inability to access the toilet independently for any reason |

| Congenital anorectal malformations – Imperforate anus – Hirschsprung’s disease |

| Idiopathic incontinence |

| Table X | Etiological factors of FI |

4. Diagnosis

Health care providers diagnose FI based on a person’s lifestyle, medical history, physical exam, and medical test results. Digital rectal examination is performed to identify resting tone and sphincter deformities. Anorectal manometry is used to measure resting and squeeze pressures; anorectal ultrasound to visualize the sphincter for injury or other deformities; electromyography (EMG) and pudendal nerve terminal motor latency (PNTML) for detecting neuromuscular damage.

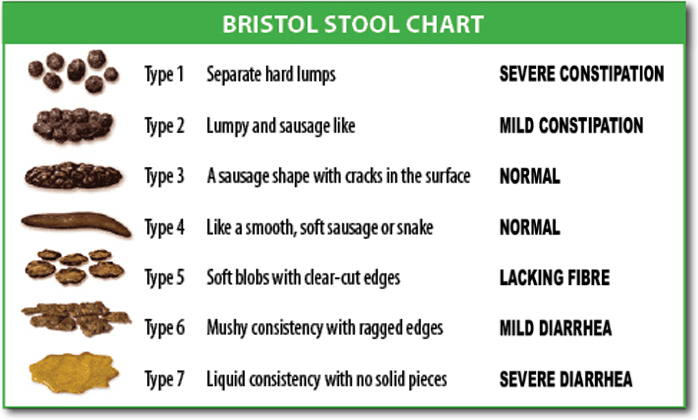

|

The ideal stool consistency is type three or four on the Bristol stool chart. Type one and two stools are hard and can be difficult to pass. Type five, six and seven stools are soft to liquid hard to retain and make it difficult for the person with FI to remain continent. |

5. Treatment

Fecal incontinence is not a disease but a symptom and can be treated. Treatment for FI may include one or more of the following:

- eating, diet, and nutrition,

- medications and bowel training,

- pelvic floor exercises and biofeedback,

- surgery,

- rectal irrigation,and

- colostomy.

- Eating, Diet, and Nutrition

A food diary should list foods eaten, portion size, and when FI occurs. After a few days, the diary may show a link between certain foods and FI. A food diary can also be helpful to a health care provider treating a person with FI.

Dietary modifications are often included as an early treatment strategy for FI, but minimal data exist to guide the recommendations on types of dietary changes. Increasing soluble fiber intake has been shown to improve FI. Overweight and obese women report a high prevalence of monthly FI associated with low dietary fiber intake.

Increasing dietary fiber may be a treatment for FI. If constipation is causing fecal incontinence, dietary may recommend drinking plenty of fluids and eating fiber-rich foods. If diarrhea is contributing to the problem, high-fiber foods can also add bulk to stools and make them less watery.

The bowel is sensitive to the amount of fibre eaten, and also to contained foods. If a diet contains too much fibre the person may develop loose stools, if the diet is lacking in fibre, the person may become constipated. People who eat too much or too litttle fibre may develop FI. Certain foods, such as figs, prunes and plums, contain a natural laxative that can affect bowel habit. Some spices, such as chilli, can also affect the bowel. Excessive consumption of foods and drinks sweetened with sorbitol (an artificial sweetener) can cause loose stools.

A conscious effort to have a bowel movement at a specific time of day, for example, after eating. Establishing when you need to use the toilet can help you gain greater control.

- Medications

If diarrhea is causing FI, medication may help. Health care providers sometimes recommend using bulk laxatives, such as Citrucel and Metamucil, to develop more solid stools that are easier to control.

Antidiarrheal medications such as loperamide or diphenoxylate may be recommended to slow down the bowels and help control the problem. If chronic constipation Opens in new window is causing FI, Laxatives may be used.

Skin should be protected from Fecal enzymes by using either a barrier cream, such as Proshield Plus Skin Protective or Sudocrem, or a barrier film such as Cavilon no sting barrier film.

- Kegel exercises and biofeedback

Kegels or pelvic floor exercises can be problematic in frail older people who often have impaired cognition, but specially trained physiotherapists teach simple exercises that can increase anal muscle strength. People learn how to strengthen pelvic floor muscles, sense when stool is ready to be released and contract the muscles if having a bowel movement at a certain time is inconvenient.

To perform Kegel exercises, contract the muscles that you would normally use to stop the flow of urine and stool. Hold the contraction for three seconds, then relax for three seconds. Repeat this pattern 10 times. As your muscles strengthen, hold the contraction longer, gradually working your way up to three sets of 10 contractions every day.

If the biofeedback session is aimed at strengthening your pelvic muscles, the practitioner will insert a slim sensor into your rectum. (In women, it is sometimes placed in the vagina, or an additional sensor may be used there.) Other electrodes will be placed on your abdomen to help record muscle contractions there.

A computer screen provides feedback about the strength of your contractions and about whether you are using the correct muscles.

If the biofeedback training is aimed at improving your ability to sense stool in the rectum, the practitioner will use anorectal manometry equipment to vary the pressure in your rectum. This is intended to increase the sensitivity of the rectum, which, in turn, helps some patients to recognize the presence of stool before the situation becomes desperate.

- Surgery

Surgery may be an option for FI that fails to improve with other treatments or for FI caused by pelvic floor or anal sphincter muscle injuries.

4.1. Phincteroplasty

The most common FI surgery, reconnects the separated ends of a sphincter muscle torn by childbirth or another injury. Sphincteroplasty is performed at a hospital by a colorectal, gynecological or general surgeon.

4.2. Artificial Anal Sphincter

Artificial anal sphincter involves placing an inflatable cuff around the anus and implanting a small pump beneath the skin that the person activates to inflate or deflate the cuff. This surgery is much less common and is performed at a hospital by a specially trained colorectal surgeon. Nonabsorbable bulking agents can be injected into the wall of the anus to bulk up the tissue around the anus.

The bulkier tissues make the opening of the anus narrower so the sphincters are able to close better. The procedure is performed in a health care provider’s office; anesthesia is not needed. Some patient can return to normal physical activities 1 week after the procedure.

4.3. Bowel Diversion

Bowel diversion is an operation that reroutes the normal movement of stool out of the body when part of the bowel is removed. The operation diverts the lower part of the small intestine or colon to an opening in the wall of the abdomen, the area between the chest and hips. An external pouch is attached to the opening to collect stool. The procedure is performed by a surgeon in a hospital and anesthesia is used.

- Rectal irrigation

This can be very benefical for some patients.

- Colostomy

Colostomy is generally considered only after other treatments have been tried.

6. Fecal Containment Devices

Containment products, such as incontinence pads and pants, are widely used to collect feces and provide a degree of protection, but should only be considered once all other treatment options have been explored.

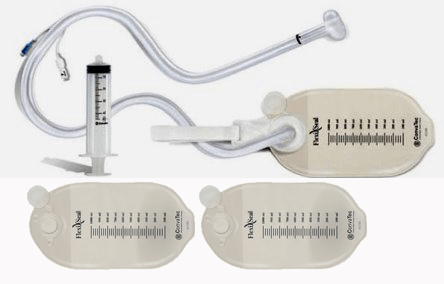

Incontinence pads are not ideal when a person is FI with profuse diarrhea or loose stools. In these cases, fecal containment device may be appropriate, such as Dignicare (Bard) or Flexi-Seal (Convatec).

|

FCD is an external drainage pouch that fits over the anus to collect stool. |

Fecal containment device (FCD) prevents contact of perineal skin with fecal matter, reducing the risk for incontinence-associated dermatitis, pressure ulcer formation, fecal contamination of wounds and reduction in frequency of diaper, clothing, and linen changes.

FCD and a bowel waste management system (BMS), which consists of an indwelling rectal catheter through which liquid or semi-liquid stool passes and is drained into an external drainage pouch. Patients are recommended to engage in monitoring fluid and electrolyte status.

FCD, nurses responsibilities involved in the placement and maintenance of an FCD, including application (and removal) of the FCD based on the treating clinician’s orders and manufacturer’s instructions, the treating clinician’s orders for the FCD, including pre-procedure analgesia. Any allegies; uses alternate materials during the procedure if allergies (e.g., latex) are noted.

See also:

- Adapted from: Fecal Incontinence: Causes, Management and Outcome. Authored By Anthony G. Catto-Smith

- Jarrett ME, Mowatt G, Glazener CM, et al. Systematic review of sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence and constipation. Br J Surg 2004;91:1559.

- Rao SS, American College of Gastroenterology Practice Parameters Committee. Diagnosis and management of fecal incontinence. American College of Gastroenterology Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterology 2004;99:1585.

- Barnett JL, Hasler WL, Camilleri M. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on anorectal testing techniques. American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology 2009; 116:732.

- Caple C, Cabrera G, Strayer DA, Incontinence, Fecal, in Women, Editor Diane Pravikoff, Cinahl Information Systems, May 6, 2011.

- Harvie HS, Arya LA, Saks EK, et al. Utility preference score measurement in women with fecal incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;204:721–726.

- Markland AD, Richter HE, Burgio KL, et al. Fecal incontinence in obese women with urinary incontinence: prevalence and role of dietary fiber intake. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;200:5661-5666.

- Woodward S, Management options for Fecal incontinence. Nursing & Residential Care 2012;14: 5.

- Bliss DZ and Norton C, Conservative Management of Fecal Incontinence. AJN 2010;110:9.

- Madoff RD, Williams JG, Caushaj PF. Fecal incontinence. N Engl J Med 1999;326:1002-07.

- Wong WD, Congliosi SM, Spencer MP, et al. The safety and efficacy of the artificial bowel sphincter for fecal incontinence: results from a multicenter cohort study. Dis Colon Rectum 2002;45:1139–53.

- Whitehead WE, Borrud L, Goode PS, et al. Fecal incontinence in U.S. adults:epidemiology and risk factors. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(2):512–17.

- Nazarko L, Fecal incontinence: diagnosis, treatment and management. Nursing & Residential Care. 2011;13(6):270–5.

- Keating JP, Stewart PJ, Eyers AA, et al. Are special investigations of value in the management of patients with fecal incontinence? Dis Colon Rectum 2012; 40:896.

- Slavin JL. Position of the American Dietetic Association: health implications of dietary fiber. Journal of the American Dietetic Associaton. 2008;108(31):1716–1731.