Transportation System

Transportation Modes and Their Characteristics

Photo courtesy of Logistics ManagementOpens in new window

Photo courtesy of Logistics ManagementOpens in new window

A variety of options is available for individuals, firms, or countries that want to move their products from one point to another. Various options for moving products from one place to another are called transportation modes. |

Road, rail, air, water, and pipelines are considered the five basic modes of transportation by most sources. In addition, digital or electronic transport is referred to as the sixth mode of transportation in some texts.

Any one or more these six distinct modes could be selected to deliver products to customers.

In addition, certain combinations are available, including rail and road, road and water, road and air, and rail and water. For example, you may transport your goods in containers from Cape Town to Kimberley by rail, and then transport to Johannesburg.

Such intermodal combinationsOpens in new window offer specialized (or less costly) services not generally available when a single transport mode is used. However, all transport modes may not be applicable or feasible options for all markets and products.

We devote the remainder of this text to discuss at length the various transport modes.

- Road

Road transport—also known as highway, truck, and motor carriage—steadily increased its share of transportation.

Throughout the 1960s, road transport became the dominant form of freight transport in the United States, replacing rail carriage, and it now accounts for 39.8% of total cargo ton-miles, which is more than 68% of actual tonnage.

The key advantages of road transport over transportation modes are its flexibility and versatility. Trucks are flexible because they offer door-to-door services without any loading or unloading between origin and destination. Truck’s versatility is made possible by having the widest range of vehicle types, enabling them to transport products of almost any size and weight over any distance.

Road transport also offers reliable and fast service to the customers. The loss and damage ratios for road transport are slightly higher than for the air shipment, but are too far lower than for the rail carriage.

Road transport generally offers faster service than railroads, especially for small shipments (less than truckload, or LTL).

For large shipments (truckload, TL), they compete directly with each other on journeys longer than 500 miles. However, for shipments larger than 100,000 pounds, rail is the dominant mode. Also, as motor carriers are more efficient in terminal, pickup, and delivery operations, they compete with air carriers, for both TL and LTL shipments that are transported 500 miles or less.

In regard to economic aspects, road transport has relatively small fixed cost, because it operates on publicly maintained networks of high-speed and often toll-free roads. However, the variable cost per kilometer is high because of fuel, tires, maintenance, and, especially, labor costs (a separate driver and cleaner are required for each vehicle).

Road transport is best suited for small shipments and high value products, moving short distances. Legislative control and driver fatigue are some problems of motor carriers’ long journeys.

- Rail

Rail carriage accounts for 37.1% of total freight ton-miles (more than 14% of actual tonnage) in the United States, which places railroads after motor carrier as the second dominant mode of transportation. However, in some countries such as the People’s Republic of China, the countries of the former Yugoslavia, and Austria, rail remains the dominant transportation mode.

Although rail service is available in almost every major city around the world, the railroad network is not as extensive as the road networks in most countries. Thus, rail system lacks the flexibility and versatility of the road transport.

Indeed, rail carriers offer terminal-to-terminal service rather than the door-to-door service provided by motor carriers. Therefore, railroads, like water, pipelines, and air transport, need to be integrated with trucks to provide door-to-door services. Also, rail-roads offer less-frequent services compared to motor carriers.

Rail transportation is relatively slow and quite unreliable, as the loss and damage ratios of rail transport for many shipments are higher than other modes. As a result, the railroad is a slow mover of both raw materials (e.g., coal, lumber, and chemicals) and low-value finished goods (e.g., tinned food, paper, and wood products).

Railroads have high fixed costs and relatively low variable costs. Expensive equipment, multishipment trains, multiproduct switching yards and terminals, and right-of-way maintenance result in high fixed costs.

However, the variable costs are low, especially for long hauls, so rail carriage generally costs less than motor and air transport on a weight basis.

Less than truckload is any quantity of freight weighing less than the amount required for the application of a truckload rate.

- Air

Air carriers transport only around 0.1% of ton-mile traffic in the United States.

Although airfreight offers the shortest time in transit (especially over long distances) of any transport mode, most shippers consider air transport as a premium emergency service because of its higher costs. However, the high cost of air transport may be traded off with inventoryOpens in new window and warehousingOpens in new window reductions or justified in some situations:

- for high-value products,

- for perishables,

- in limited marketing periods, and

- in an emergency.

The portion of total product costs dedicated to transportationOpens in new window is an important issue for most shippers. The high price of airfreight consumes a greater portion of low-valued products’ total costs, so it is not economically justifiable for these items. This could be why air carriers usually handle high-value items.

Total transit time (from pickup at the vendor to delivery to the customer) is important to shippers and the customers. From this point of view, well-managed surface carriers can compete favorably with air carriers, especially on short and medium hauls.

Even though air carriers provide rapid time in transit from terminal to terminal, they may spend too much time on the ground (e.g., for pickup, delivery, delays and congestions, and waiting for scheduled aircraft departures).

Loss and damage ratios resulting from transportation by air are considered lower than the other modes. The classic study by Lewis et al. shows that the ratio of claim costs to freight revenue was only about 60% of those for road and rail.

Airline companies generally own neither airways nor airports. Air spaces and air terminals are usually developed and maintained with public funds, so fixed air freight costs (including aircraft purchases, specialized handling systems, and cargo containers) are lower than railOpens in new window, waterOpens in new window, and pipelineOpens in new window.

Air-transport variable expenses are extremely high because of fuel, maintenance, and the labor intensity of both in-flight and ground crew. Variable costs are reduced by the length of journey because takeoffs and landings are the most inefficient phases of aircraft operation.

Moreover, increasing shipment sizes reduces the variable operating cost per ton-mile. Hence, variable costs are influenced by both distance and shipment size.

- Water

Water carriage—as the oldest mode of transportation—accounts for 5% of total freight ton-miles (around 3.3% of actual tonnage) in the United States. Sampson et al. describe the nature and characteristics of water carriage as follows:

| Water carriage by nature is particularly suited for movements of heavy, bulky, low-value-per-unit commodities that can be loaded and unloaded efficiently by mechanical means in situations where speed is not of primary importance, where the commodities shipped are not particularly susceptible to shipping damage or theft, and where accompanying land movements are unnecessary. |

As already mentioned, the majority of commodities transported by water are semiprocessed and raw materials; thus, water transportation competes primarily with rail and pipeline. Water carriage can be broken into the following distinct categories:

- Inland waterways (such as rivers and canals)

- Lakes

- Coastal and intercoastal oceans

- International deep sea

Water transportation service is limited in scope, mainly for two reasons: its limited range of operation and speed. Water service is confined to waterway systems; thus, unless the origin and the destination of movement are located on waterways, it needs to be supplemented by another transportation mode (rail or motor carrier).

In addition, the average speed of water carriage is less than rail transport, and the availability and dependability of its service are greatly influenced by weather.

Containers are used for many domestic and most international water shipments. Moving freight in containers on containerized ships affects the intermodal transferOpens in new window by reducing handling time and shortening total transit time. It also reduces staffing needs and allows shippers to take advantage of volume shipping rates.

Finally, containers reduce loss and damage. For all these reasons, high-value commodities (especially those in foreign shipments) are shipped in containers and containerized ships.

Loss and damage costs for water carriage are lower in comparison with other transportation modes because damage is not much of a concern with low-valued bulk commodities. Also, because large inventories are often maintained by buyers, losses from delays are not serious. For high-valued products, claims are much higher; approximately 4% of ocean-ship revenues. Most damages are caused by rough handling during loading and unloading operations, so substantial packaging is needed to protect goods.

Regardless of the limitations inherent in water transportation, water is the least inexpensive mode for transporting high-bulk, low-value freights. The fixed cost of water carriage is mainly found in terminal facilities and transport equipment.

Although water carriers have to develop and operate their own terminals, rights-of-way and harbors are developed and maintained publicly. This moderates water-transport fixed costs, putting the mode between rail and motor carriages.

Water-transport variable costs, including waterway charges and transport equipment operation costs, are very low. Because of the high fixed cost and low line-haul costs of water carriage, its costs per ton-mile decrease significantly as the distance and shipment size increase.

- Pipeline

Pipeline systems were mainly developed for transporting large volumes of products, often over long distances. Pipelines tend to be product specific, which means they are used for only one particular type of product throughout their design life.

A limited number of products can be transported by pipelines, including natural gas, crude oil, refined petroleum products, chemicals, water, and slurry products.

Although product movement through pipelines is very slow (only 3 to 4 miles per hour), their effective speed is much greater than the other modes because they operate 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

For transit time, pipeline service is the most dependable of all modes because of the following factors:

- Pumping equipment is highly reliable, so losses and damage because of pipeline leaks or breaks are extremely rare.

- Climatic conditions have mineral effects on products moving in pipelines, so weather is not a significant factor.

- Pipelines are not labor intensive, so strikes or employee absences have little effect on their operations.

- Computers are used to monitor and control the flows of products within the pipelines.

Losses and damage costs from transporting by pipeline systems are low because:

- liquid and gases are not subject to damage to the same degree as manufactured products, and

- there are fewer types of danger throughout a pipeline operation.

Pipelines have the highest fixed cost and the lowest variable cost among transportation modes. High fixed costs result from right-of-way, construction, and requirements for control station and pumping capacity.

To spread these high capital costs, and to be competitive with other modes, pipelines must operate at high volumes. The variable costs are extremely low and mainly include the power for moving products, because, as noted, pipelines are not labor intensive.

- Digital

Digital or electronic transport is the fastest mode of transportation. Besides its high speed, digital transport is cost efficient and benefits from its high accessibility and flexibility. However, only a limited range of products can be shipped by this mode, including electric energy, data, and products such as texts, pictures, music, movies, and software, all of which are composed of data.

Most logistics references do not cite digital transport as a transportation mode because of its limited product options. However, someday, technology may allow us to convert matter to energy, transport it to desired destination, and convert it back to matter again.

Any one or more of the six above-mentioned transportation modes can be a viable option for a company or individual who wants to move products from one point to another.

Shippers take several factors into account in selecting the proper transportation modes. The company and its customers’ needs, the characteristics of the transportation modes, and the nature of traffic are the main factors that should be considered in the modal choice.

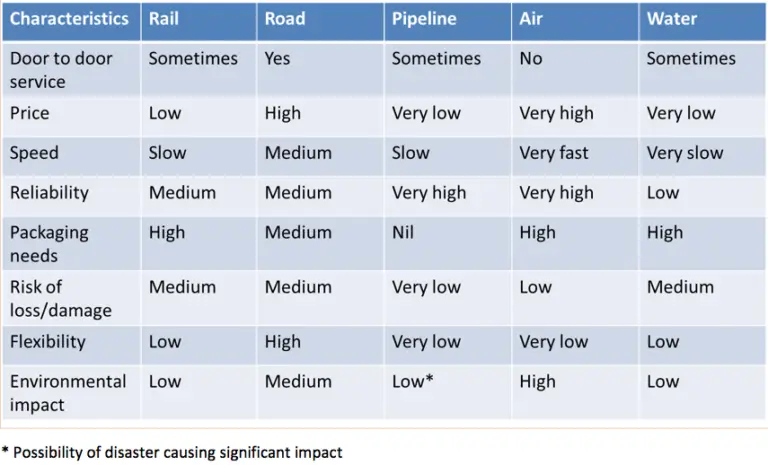

Figure X-1 excludes digital transportation mode but summarizes the general and service characteristics of the five common transportation modes, based on the work of Gourdin K.

Figure X-1. Basic modes of transportation. Adapted from Gourdin K, Global Logistics Management 2006

Figure X-1. Basic modes of transportation. Adapted from Gourdin K, Global Logistics Management 2006

|

See also:

- J.C. Johnson, D.F. Wood, D.L. Wardlow, P.R. Murphy, Contemporary Logistics, seventh ed., Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 1999, pp. 1 – 21.

- A. Rushton, P. Crouche, P. Baker, The Handbook of Logistics and Distribution Management, third ed., Kogan Page, London, 2006.

- S.C. Ailawadi, R. Singh, Logistics Management, Prentice Hall of India, New Delhi, 2005.

- R.H. Ballou, Business Logistics/Supply Chain Management: Planning, Organizing, and Controlling the Supply Chain, fifth ed., Pearson-Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2004.

- J.R. Stock, D.M. Lambert, Strategic Logistics Management, fourth ed., Irwin McGraw-Hill, New York, 2001.

- G. Ghiani, G. Laporte, R. Musmanno, Introduction to Logistics Systems Planning and Control, John Wiley & Sons, NJ, 2004, pp. 6 – 20.

- M. Hugos, Essentials of Supply Chain Management, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken NJ, 2003, pp. 1 – 15.

- H.T. Lewis, J.W. Culliton, J.D. Steel, The Role of Air Freight in Physical Distribution, Division of Research, Graduate School of Business Administration, Harvard University, Boston, MA, 1956, p. 82.

- D. Riopel, A. Langevin, J.F. Campbell, The network of logistics decisions, in: A. Langevin, D. Riopel (Eds.), Logistics Systems: Design and Optimization, Springer, New York, 2005, pp. 12–17.

- M. Browne, J. Allen, Logistics of food transport, in: R. Heap, M. Kierstan, G. Ford (Eds.) Food Transportation, Blackie Academic & Professional, London, 1998, pp. 22–25.

- J. Drury, Towards More Efficient Order Picking, IMM Monograph No. 1, The Institute of Materials Management, Cranfield, 1988.