Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Introduction and Clinical Features of PTSD

|

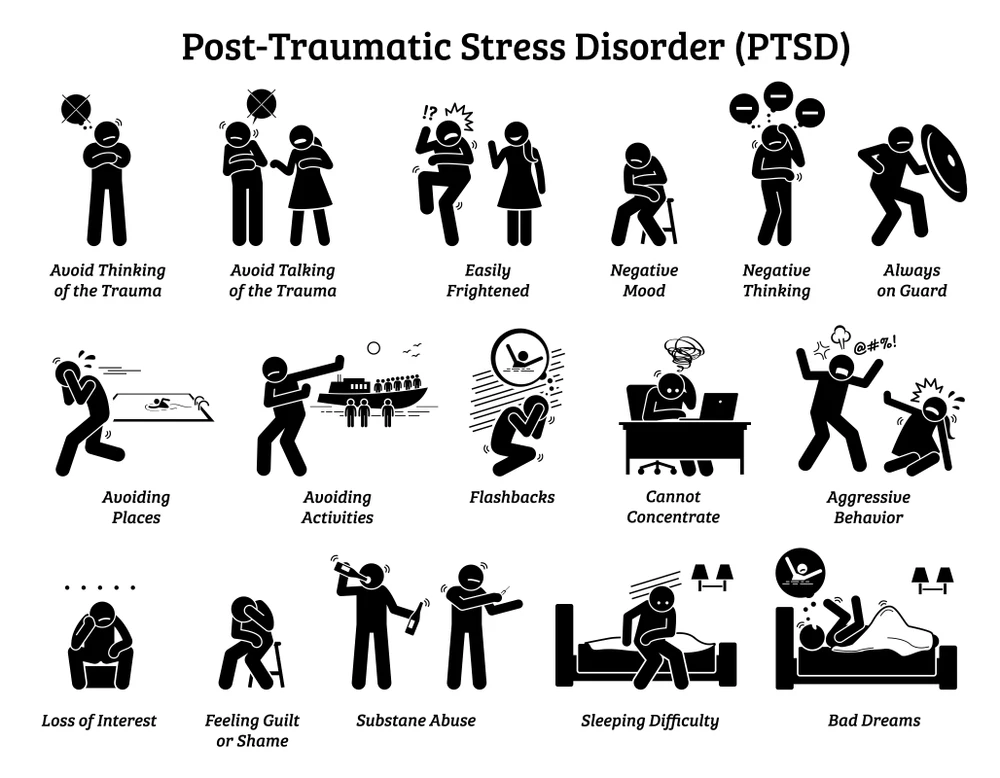

| Image courtesy of The BLACKBERRY Center Opens in new window |

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a trauma and stress-related disorder whose symptoms occur following exposure to a traumatic stressor (i.e., terrifying event)—either experiencing or witnessing it. Symptoms of PTSD may include flashbacks, nightmares, and severe anxiety, as well as uncontrollable thoughts about the event.

As classified in DSM-4, PTSD consists in three (3) types:

- the acute type, of which duration of symptoms is less than three months

- the chronic type, whose symptoms lasts for three months or more, and

- the delayed onset, of which onset of symptoms resurface in a more severe form when a similar event occurs at least six months after the traumatic stressor.

When chronic, PTSD can bring persistent suffering and impaired function—it can disrupt whole life, relationships, health, and enjoyment of everyday activities.

Those at particular risk for PTSD include children and adolescents, women, soldiers, refugees and survivors of genocide, sexual orientation minorities, racial and ethnic minorities, patients with burns, injuries and medical trauma, and victims of rape, violence, accidents, and disasters.

DSM-IV-TR Diagnostic Criteria for PTSD

| Table X1 | Keywords in DSM-IV Diagnostic Criteria for PTSD | |

|---|---|

| Keyword | Meaning |

| Arousal | Cluster of PTSD symptoms that includes concentration problems, anger, exaggerated startle response, sleep disturbance, and overalertness. |

| Avoidance | Cluster of PTSD symptoms that includes behavioral and psychic avoidance, such as avoidance of thoughts, feelings, and reminders of the trauma, emotional numbing, loss of interest in activities, disconnection from others, psychogenic amnesia, and a sense of foreshortened future. |

| Reexperiencing | Cluster of PTSD symptoms that includes experiencing the trauma in the form of nightmares, flashbacks, or intrusive distressing thoughts, or becoming intensely emotionally upset or having physiological arousal on exposure to reminders of the trauma. |

| Trauma (Stressor) | An event, witnessed or experienced, in which there is threat of death, injury, or physical integrity, and during which an individual feels terrified, horrified, or helpless. |

As described in DSM-IV Opens in new window, posttraumatic stress disorder is a set of symptoms that begins after a trauma and persists for at least one (1) month. The symptoms fall into three clusters.

- First, the individual must reexperience the trauma in one of the following ways: nightmares, flashbacks, or intrusive and distressing thoughts about the event; or intense emotional distress or physiological reactivity when reminded of the event.

- Second, the individual must have three of the following avoidance symptoms: avoidance of thoughts or feelings related to the trauma, avoidance of trauma reminders, psychogenic amnesia, emotional numbing, detachment or estrangement from others, decreased interest in leisure activities, or a sense of foreshortened future.

- Third, the individual must experience two of the following arousal symptoms: difficulty falling or staying asleep, difficulty concentrating, irritability or outbursts of anger, hypervigilance, or an exaggerated startle response.

To meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD, the symptoms must cause significant impairment in daily functioning.

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for PTSD

While many criteria are retained from the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), there are significant changes in the fifth edition (DSM-5) for PTSD, with greater clarity, explanation, and some modified and added criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) (see Table X2).

The avoidance and numbing criterion was divided into two clusters, with emotional numbing no longer required to establish a diagnosis but included as a potential manifestation of the negative alterations of cognition and mood symptom cluster.

Also, while acute and chronic PTSD are no longer distinguished as part of the diagnosis (it is a descriptor) in DSM-5, delayed expression is now specified if full diagnosis criteria are not met until 6 months after the traumatic event.

In addition, with dissociative symptoms is now specified in persons who meet full diagnostic criteria and experience either persistent or recurrent symptoms of depersonalization of derealization (or both). Finally, modified criteria define PTSD for children 6 years and younger and its variants (i.e., with depersonalization, derealization, and/or delayed expression).

| Table X2 | Summary of DSM-5 PTSD Criteria A-H & Subtypes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion | Description | Example | Required | Difference from DSM-IV |

| Criterion A | Experiencing a traumatic event | Direct experiencing, in-person witnessing, learning someone close was exposed to a severe stressor | Direct: violent or accidental. Indirect: extreme exposure. | Criterion A2, reaction of fear, helplessness, or horror dropped. |

| Table X2 Continued | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion | Description | Example | Required | Difference from DSM-IV |

| Criterion B | One or more intrusion symptoms associated with the trauma(s), beginning afterwards. |

| One or more. | No change |

| Criterion C | Avoidance of reminders | Avoidance of stimuli linked to the trauma:

| One or both. | This cluster is separated from Criterion D. |

| Table X2 Continued | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion | Description | Example | Required | Difference from DSM-IV |

| Criterion D | Negative alterations in cognitions and mood beginning or worsening after the trauma |

| Two or more. | This cluster is separated from Criterion C. |

| Table X2 Continued | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion | Description | Example | Required | Difference from DSM-IV |

| Criterion E | Alterations in arousal and reactivity |

| Two or more. | #2 is added. |

| Criterion F | Duration | Duration of the disturbance (Criteria B, C, D, and E) is more than 1 month. | Acute Stress Disorder is < 1 month. | No change |

| Criterion G | Function | The disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other functioning. | Impaired function required in one of these areas. | No change. |

| Criterion H | Exclusion | Not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or another medical condition. | Symptoms not from other medical causes. | This is a new addition. |

| Table X2 Continued | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion | Description | Example | Required | Difference from DSM-IV |

| Subtypes | Specifiers | Preschool: Criteria for children under 6. | 4 symptoms required. | This is new. |

| Dissociative: added if there are dissociative symptoms, either depersonalization or derealization. | Added symptoms. | This is news. | ||

| Delayed expression: emergence of symptoms after a time they were not present or did not meet criteria. | No change from Delayed Onset. | |||

Course of PTSD

The course of PTSD is variable. For the majority of individuals, symptoms begin immediately after the trauma, although some appear to have a delayed reaction. During the first 3 months after the trauma, the individual is said to have acute PTSD, whereas chronic PTSD is defined as symptoms persisting beyond 3 months.

Case Example

Some combat veterans have been so traumatized by their experience of death and destruction that the vividness of horrifying memories becomes an irrepressible tormentor.

One traumatized combat veteran, for example, was having a sandwich and a beer at a local pub with a couple he knew. The couple’s twelve-year-old son walked in, the veteran picked up the lad and was going to give him a friendly kiss on the forehead; but suddenly he flashed back to a twelve-year-old boy in Vietnam who approached him with a live hand grenade.

Instantly his mind was back in Vietnam, and he threw the child over the bar, knocked his friend to the ground and started choking him to death. His friend’s wife began kicking him in the ribs. He grabbed her by the ankles, swung her around and around, flung her over the pool table, grabbed a pool stick, splintered it on the pool table, and charged his friend with the splintered end—all in less than one minute.

His friend raced out the door and across the highway. As the veteran followed in chase, the cold air hit his face. He saw cars driving on the highway and returned to current reality. His only recollection of the event was a hallucination of asking a Vietnamese woman, in Vietnamese, to see her identification pass.

This is a case of acute posttraumatic stress disorder with an extreme hallucinatory flashback. It represents a step back in time to earlier combat reality and behavior. Even his chemistry, physiology, and body movements matched those of the earlier time. He was strictly in a survival mode—which is highly adaptive for future combat. It enables the person to shift to autopilot and instantly respond to an attack, but it is maladaptive for social interaction.

This veteran decided never to drink beer again. Abusive substances serve as “grease in the mechanism” and facilitate a shift to the earlier time.

Symptoms can fluctuate over time between diagnosis of PTSD, subthreshold symptoms, and few or no symptoms. Recovery is affected by a number of factors, including perception of oneself and one’s surroundings, actual social support, life stress, coping style, and personality.

Diagnostic Assessment

Certain conditions or factors are necessary in order to interview people who have been exposed to a traumatic event. This requires skill and consideration for the specific trauma or stressor they have endured in order to foster a relationship, obtain their history, assess for possible posttraumatic stress symptomatology, make a diagnosis, and plan treatment together with the patient.

Building a Therapeutic Alliance

The therapeutic alliance refers to the capacity to form a trusting relationship with the therapist based on the early maternal/child relationship (Zetzel, 1956). Elements of an alliance around diagnosis and therapy includes goals, tasks, and bonds.

For effective therapy the patient and therapist must agree on common goals and on the therapeutic tasks to achieve them. In the course of working together on these, the bond of patient and therapist becomes a positive attachment of trust and confidence.

Objective and empathic attentive listening and inquiry, with open-ended questions about the patient’s psychiatric history including medical history, provides a basis for broadly understanding the origins of the patient’s distress, experience over time, and his or her own explanation for the causes of the illness. The diagnostic process is of practical use in gathering information about the patient’s strengths and vulnerabilities, capacity for self-expression, and the person’s explanatory model for his or her problem or illness.

This process, elicited with empathy for the patient’s distress, facilitates gathering the symptoms s/he has and concluding what the diagnosis is, communicating understanding, and building a therapeutic alliance with the patient.

Another element in establishing a trusting therapeutic alliance in relation to traumatic experiences occurs through empathic interest in the patient’s bodily feelings related to and after the trauma especially whether or not the patient is experiencing current physical pain, and what its location, duration and severity is (Stoddard & Saxe, 2001).

Assessment Considerations in Children

Diagnostic assessment varies for children under 6 years based on the new PTSD diagnostic criteria for that age group. School-age children or adolescents may need to play or talk about their latest video game before being able to share information about what they have endured (per American Psychiatric Association guidelines and others).

Some patients may choose not to speak about their traumatic event initially, requiring more than one session to establish trust and gentle encouragement, before elaborating about it. Shy, fearful, withdrawn, or medicated patients may have difficulty and may need specific direct questions if information about traumatic experiences are to be elicited.

Diagnostic Criteria

The DSM-5 recognizes that in addition to anxiety and fear-based symptomatology, many individuals with PTSD have clinical characteristics which are more anhedonic and dysphoric, consistent with the high comorbidity of PTSD with depression, and also externalizing angry and aggressive or dissociative symptoms.

In DSM-5, there are five clusters for children over 6 years, adolescents, and adults. They are “A-E” with varying numbers of required symptoms, and requirements E, F, and G also.

“A” is exposure in one or more of four ways: to actual or threatened death, serious injury or sexual violence directly, witnessing, learning about it occurring to a close family member or friend, or repeated and extreme exposure to aversive details of the events.

“B” is presence of at least one of five intrusion symptoms beginning after the traumatic event, including distressing memories, distressing dreams, dissociative reactions, intense distress at exposure to internal or external cues, or marked physiological reactions to reminders.

“C” are at least one of two persistent avoidance symptoms, including avoidance of or efforts to avoid distressing memories, thoughts, or feelings about or closely associated with the event, or avoidance of or efforts to avoid external reminders that arouse distressing memories, thoughts, or feelings about or closely associated with the traumatic event(s).

“D” are at least two or more of seven negative alterations in cognitions and mood associated with the traumatic event(s), including:

- inability to remember (typically dissociative amnesia not due to head injury or substances);

- persistent negative beliefs or expectations about oneself or the world;

- persistent distorted cognitions about the cause or consequences of the traumatic event(s) leading the individual to blame self or others;

- persistent negative emotions such as fear, horror, anger, guilt, or shame;

- markedly diminished interest in significant activities;

- feelings of estrangement or detachment from others; or

- persistent inability to experience positive emotions; and at least two of six marked alterations in arousal or reactivity associated with the traumatic event(s): irritability or angry outbursts, reckless and self-destructive behavior, hypervigilance, exaggerated startle response, problems concentrating, or sleep disturbances such as difficulty falling or staying asleep or restless sleep.

Therefore, the minimum number of required symptoms is a total of seven symptoms, including at least one from each cluster, in order to make a diagnosis of PTSD.

Arriving at a diagnosis only occurs after eliciting responses regarding the required symptom criteria which is normally elicited directly but can be done over time, or using a symptom and criterion checklist, or by asking a relative or caregiver in the case of a child or elder under the care of a family member or caregiver.

“F” specifies that the duration must be at least one month.

“G” specifies that the disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas (e.g., school) functioning.

“H” specifies that the disturbance is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance including drugs and medications or to another medical illness.

Assessment Instruments

The clinical interview remains the “gold standard” for the assessment of PTSD for several reasons:

- an interview allows for a detailed explanation of the nature of the traumatic stressor or stressors,

- an interactive process allows for the best understanding of confusing symptoms (the ability to distinguish or articulate the difference between intrusive recollections and flashbacks), and

- the clinical interview allows for the progressive elaboration of symptoms in a manner sensitive to the emotional needs of the patient at the time of assessment.

However, several clinician-administered and self-report instruments can be used to obtain diagnostic information in the aftermath of traumatic exposure. The most widely used instruments are listed in Table X3.

| Table X3 | Instrument Used in the Assessment and Diagnosis of PTSD |

|---|

|

Several of these instruments were developed originally for DSM-IV but have since been adapted for and used extensively in clinical and research environments to quantify diagnostic criteria and measure DSM-5 PTSD symptom severity.

The PTSD module of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV) used open-ended questions about traumatic exposure (supplemented with examples) as well as questions about each of the 17 symptoms of PTSD, duration of disturbance, and functional impairment (First et al., 1995).

The PTSD module SCID for DSM-5 has been developed in a similar format asking open-ended questions about each of the 20 symptoms of DSM-5 PTSD and is presently being validated. The most commonly used PTSD measure in research prior to the transition to DSM-5 was the Clinician-Administered PTSD scale (CAPS), which asked the patient about the frequency and severity of each symptom rating each on a scale of 1 to 4 yielding a total score of between zero and 136.

A minimum score of 50 was used as an entry criterion for PTSD research (Blake et al., 1990). The CAPS has been revised to reflect the new diagnostic criteria, and new scoring and threshold scores have been developed allowing a clinician to assess severity (mild, moderate, severe) as well as current (past month and/or past week) as well as lifetime diagnosis (Weathers, et al. 2013).

The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 is a self-report measure that can be completed by patients. It takes approximately 5 to 10 minutes to complete, and results are easily interpreted by clinicians according to a variety of scoring rules (Weathers, et al., 2013). Such a report can be used to assess symptom severity at initial presentation and to track symptoms as treatment progresses.

Regardless of the interview techniques or instruments used to quantify symptoms, it is important to note that the DSM-5 specifies that the diagnosis should better explain the symptoms (e.g., why symptoms represent PTSD, a trauma- and stressor-related disorder), than a depressive, anxiety, or dissociative disorder or a substance use disorder or other general medical condition.

Treatment Considerations

At the conclusion of the diagnostic evaluation, the final step is to discuss with the patient the presence (or absence) of the PTSD diagnosis, the prognosis, and then to engage in a discussion about whether and when to proceed with treatment.

The planning, designing, and carrying out the course of treatment will often differ for patients in special populations, with different trauma experiences, medical histories, family or cultural characteristics, or resources and social supports.

It is important to listen and observe the patient’s response to learning the presence or absence of the diagnosis of PTSD since it can be experienced in varying ways such as being upsetting, confirmatory, alien, supportive, or stigmatizing.

For some patients, anxiety, language difficulty, cultural barriers, a general mistrust of clinicians, or other factors may interfere with their understanding of either this or an alternative diagnosis as potentially helpful to them.

They may require simpler explanation, or explanations responding to their questions, before the meaning of the diagnosis and what may help becomes clear.

Treatment

- Psychotherapies

These include psychodynamic (generally for complicated and chronic PTSD), CBT, eye-movement desensitization and relaxation (EMDR), and others.

CBT treatment interventions—including exposure and cognitive processing treatments—are the most evidence supported and are based on cognitive psychology and the idea that traumatic experience results in fear memories and overgeneralized response to reminders of the traumatic experience.

Behavior therapy focuses on identifying and extinguishing maladaptive behavioral responses to triggers or cues of the fear memory. CBT is thus targeted to neurocircuitry involved in thoughts and behaviors, or areas of the brain or circuits devoted to particular functions such as autonomic responsivity, emotional regulation, and executive functioning (Bisson & Andrew, 2007).

Clinical trials have also demonstrated the efficacy of EMDR in PTSD—although subsequent dismantling studies have suggested that the eye-movement component of this exposure-based cognitive therapy is unnecessary (Benedek et al., 2009).

- Somatic and/or Pharmacotherapy

A range of medications and other somatic approaches to the treatment of PTSD have been evaluated in clinical trials in the last quarter-century.

Importantly, pharmacotherapies for PTSD presently considered “first-line” on the basis of evidence from randomized controlled trials include selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and with regard to associated sleep disturbance and nightmares—alpha-1 antagonists (Capehart, 2017).

Neurostimulation techniques including vagus nerve stimulation, transcranial magnetic stimulation, and deep brain stimulation are currently being explored, as are alternative approaches such animal-assisted therapy, yoga, meditation, and acupuncture—although thus far only the latter has demonstrated efficacy in well-designed clinical trials.

See also:

- American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

- Davidson, J. R. T., & Foa, E. B. (Eds.). (1993). Post-traumatic stress disorder: DSM-IV and beyond. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

- Abram KM, Teplin LA, Charles DR, Longworth SL, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK. Posttraumatic stress disorder and trauma in youth in juvenile detention. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004 Apr;61(4):403-410.

- Armour C. The underlying dimensionality of PTSD in the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: where are we going? Eur J Psychotraumatology. 2015;6:28074.

- Bisson J, Andrew M. Psychological treatments of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;3:CD003388.

- Bremner JD. Does stress damage the brain? Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:797-805.

- Cepehart B. Psychopharmacology of PTSD. Paper presented at MGH Psychiatry Academy, March 20, 2017.

- Davidson JT, BookSW,ColketJT, et al. (1997). Assessment of a new self-rating scale of post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:153-160.

- Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, Cohen JA. Effective treatments for PTSD: Practice guidelines from the international society for traumatic stress studies, 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2008.

- Germain A. Sleep disturbance and the hallmark of PTSD: Where are we now? Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:372-382.

- Houston AA, Webb-Murphy J, Delaney E. (2013). From DSM-IV-R to DSM-5: Changes in posttraumatic stress disorder. COSC Research Facilitation. Retrieved from www.nccosc.navy.mil

- Kaiser AP, Wang J, Davison EH, Park CL, Stellman, JM. Stressful and positive experiences of women who served in Vietnam. J Women Aging. 2017;29(1):26-38. doi:10.1080/08952841.2015.1019812

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson, CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048-1060.

- Palmer BW, Raskind MA. Posttraumatic stress disorder and aging. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016 Mar;24(3):177.