Why-reasons in Reverse Logistics

The Reasons for Products Going Back in the Supply Chain

Graphics courtesy of Yusen LogisticsOpens in new window

Graphics courtesy of Yusen LogisticsOpens in new window

Roughly speaking, productsOpens in new window are returned or discarded because either they do not function (anymore) properly or because they or their function are no longer needed. |

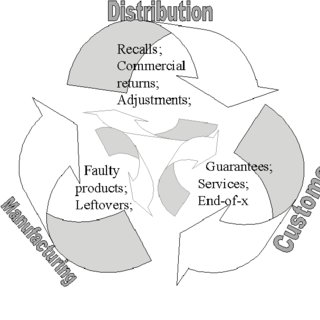

Let us next elaborate these return or discard reasons in more detail. We can list them according to the usual supply chain hierarchy: starting with manufacturing and going to distribution until the products reach the customer. Therefore, we differentiate between manufacturing returns, distribution returns, and customer returns.

- Manufacturing Returns

We define manufacturing returns as all those cases where components or products have to be recovered in the production phase.

This occurs for a variety of reasons. Raw materials may be left over, intermediate or final products may fail quality checks and have to be reworked, products may be left over during production, or by-products may result from production.

Raw material surplus and production leftovers represent the ‘product not needed’ category, while quality-control returns fit in the ‘faulty’ category. In sum, manufacturing returns include:

|

- Distribution Returns

Distribution returns refers to all those returns that are initiated during the distribution phase. It refers to product recalls, commercial returns, stock adjustments, and functional returns.

- Product recalls are products recollected because of safety or health problems with the products, and the manufacturer or a supplier usually initiates them.

- B2B commercial returns are all those returns where a retailer has a contractual option to return products to the supplier.

This can refer to wrong/damaged deliveries, to products with a too-short remaining shelf life, or to unsold products that retailers or distributors return to the wholesaler or manufacturer. The latter include outdated products, such as those products whose shelf life has been too long (e.g. pharmaceuticals and food) and may no longer be sold.

- Stock adjustments take place when an actor in the chain redistributes stocks, for instance between warehouses or shops, e.g. in the case of seasonal products (De Koster et al., 2002).

- Finally, functional returns concern all the products whose inherent function keeps them going backward and forward in the chain.

An obvious example is the one of pallets as distribution carriers: their function is to carry other products and they can serve this purpose several times. Other examples are crates, containers, and packaging. Summarizing, distribution returns include:

|

- Customer Returns

The third group consists of customer returns, i.e. those returns initiated once the product has at least reached the final customer. Again there are a variety of reasons to return the products:

|

The reasons have been listed more or less according to the life cycle of a product.

Reimbursement guarantees give customers the opportunity to change their minds about purchasing (commonly shortly after having received/acquired the product) when their needs or expectations are not met.

The list of underlying causes is long, for example with respect to clothes, where dissatisfaction may be due to size, color, fabric properties, and so forth. Independent of the underlying causes, when a customer returns a new product benefitting from a money-back guarantee or an equivalent, we are in the presence of B2C commercial returns.

The next two reasons, warranty and service returns, refer mostly to an incorrect functioning of the product during use, or to a service that is associated with the product and from which the customer can benefit.

Initially, customers benefiting from a warranty can return products that do not (seem to) meet the promised quality standards. Sometimes these returns can be repaired or a customer gets a new product or his or her money back, upon which the returned product needs recovery.

After the warranty period has expired, customers can still benefit from maintenance or repair services, but they no longer have a right to get a substitute product for free. Products can be repaired at the customer’s site or be sent back for repair. In the former case, there are many returns in the form of spare parts in the service supply chain, since in advance it is hard to know precisely which parts will be needed for the repair.

End-of-use returns refer to those situations where the user has a return opportunity at a certain life stage of the product. This refers to leasing cases and returnable containers like bottles, but also to returns to second-hand markets like bibliofind, a division of amazon.com for used books.

Finally, end-of-life returns refer to those returns where the product is at the end of its economic or physical life as it is. They are either returned to the OEM because of legal product take-back obligations or other companies like brokers take them for material and value-added recovery (see the How sectionOpens in new window).

Figure X-2. Return reasons for reverse logistics | Credit: ResearchGateOpens in new window

Figure X-2. Return reasons for reverse logistics | Credit: ResearchGateOpens in new window

|

Figure X-2 summarizes the return reasons for Reverse Logistics in the three stages of a supply chain: manufacturing, distribution, and customer.

The Series:

- What Is Reverse Logistics?Opens in new window

- Forces Driving Companies to Engage in Reverse Logistics (Why-drivers)Opens in new window

- Reasons for Products Being Returned in the Supply Chain(Why-reasons)Opens in new window

- Reverse Logistics Processes: How are Returns Processed?Opens in new window

- Types & Characteristics of Returned Products: What Is Being Returned? Opens in new window

- Who Are Executing Reverse Logistics Activities? Opens in new window

- Barry, J., Girard, G., Perras, C. (1993): Logistics shifts into reverse. In: Journal of European Business 5, Sept./Oct. 1993, pp. 34 – 38.

- Ayres, R. U., Ferrer, G., Leynseele, T. van (1997): Eco-efficiency, asset recovery and remanufacturing. In: European Management Journal 15, pp. 557 – 574.

- Carter, C.R., Ellram, L. M. (1998): Reverse logistics: A review of the literature and framework for future investigation. In: Journal of business logistics 19, No. 1, pp. 85 – 102.

- Elkington, J., Knight, P., Hailes, J. (1991): The green business guide. Victor Gollancz, London.

- Fleischmann, M. (2001): Quantitative models for reverse logistics. Springer, Berlin et al.

- Harrington, L. (1994): The art of reverse logistics. In: Inbound logistics 14, pp. 29 – 36.