Schizoaffective Disorder

Introduction & Clinical Features

|

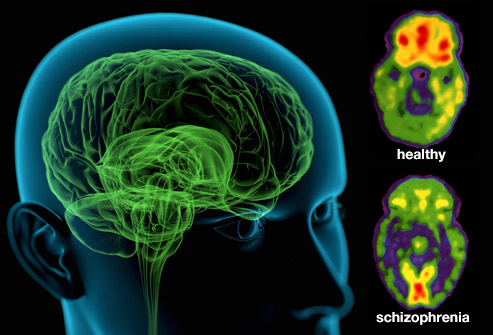

| Image courtesy of WebMD® Opens in new window Schizoaffective disorder has elements of both schizophrenia and a mood (affective) disorder. It is generally considered to be a form of schizophrenia, lying on the schizophrenia spectrum. There are two subtypes of schizoaffective disorder: the depressive subtype is characterized by major depressive episodes, while the bipolar subtype is characterized by manic episodes with or without depressive symptoms. |

Schizoaffective disorder presents with symptoms of a major mood disorder (manic, depressive, or mixed) concurrent with symptoms of schizophrenia. Mood symptoms are prominent throughout the course of the illness, except for minimum two-week period during which there are positive psychotic symptoms (hallucinations or delusions) without prominent mood symptoms. It can be difficult to distinguish schizoaffective disorder from schizophrenia and from bipolar disorder.

Characteristic symptoms of schizoaffective disorder generally fall into four categories: positive symptoms, negative symptoms, symptoms of mania, and depression:

- Positive symptoms are the presence of thoughts, perceptions, and behaviors that are usually absent in people without schizoaffective disorder. These include hallucinations (seeing and hearing things that are not there), delusions (false beliefs), and thought disturbances (e.g., jumping from topic to topic, making up new words, speech that does not make sense).

- Negative symptoms are an absence of behaviors, thoughts, or perceptions that would normally be present in people without schizoaffective disorder. These include blunted affect (lack of expression), apathy, anhedonia (inability to experience pleasure), poverty of speech (not saying much), and inattention. Residual and negative symptoms are usually less severe and less chronic with schizoaffective disorder than those seen in schizophrenia.

- Symptoms of mania involve an excess of behavior, activity, or mood. These may include euphoric or expansive mood, irritability, inflated self-esteem or grandiosity, decreased need for sleep, rapid or pressured speech, racing thoughts, distractibility, increased goal-directed activity (a great deal of time spent pursuing specific goals, at work, school, or sexually), and excessive involvement in pleasurable activities with high potential for negative consequences (e.g., increased substance use, spending sprees, sexual indiscretions, risky business ventures).

- Depressive symptoms involve a deficit of activity and mood. Symptoms include depressed mood, sadness, diminished interest or pleasure (anhedonia), changes in appetite or sleeping patterns, decreased activity level, fatigue, loss of energy, feelings of worthlessness, inappropriate guilt, decreased concentration, inability to make decisions, and preoccupation with thoughts of death.

Schizoaffective disorder usually starts in late adolescence or early adulthood, most often between the ages of 16 and 30. Because it is difficult to differentiate schizoaffective disorder from schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, detailed information on the prevalence and demographics of schizoaffective disorder is lacking. Estimates suggest that there is a higher incidence of schizoaffective disorder in women than in men. The bipolar subtype of schizoaffective disorder is more common in young adults, while the depressive subtype is more common in older adults (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The bipolar lasts a lifetime, although symptoms and functioning can improve with time and treatment. Symptoms severity also varies over time, sometimes requiring hospitalization. The cause of schizoaffective disorder is not known, although current theories suggest that an imbalance of the neurotransmitter dopamine (a chemical messenger) is at the root of both schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder.

Features associated with schizoaffective disorder include poor occupational functioning, a restricted range of social contact, difficulties with self-care, increased risk of suicide, increased risk for later developing episodes of pure mood disorder, schizophrenia, or schizophreniform disorder (similar to schizophrenia). Schizoaffective disorder is also associated with alcohol and other substance-related disorders (resulting from attempts to self-medicate). Anosognosia (i.e., poor insight that one is ill) is also common in schizoaffective disorder, but the deficits in insight may be less severe and pervasive than in schizophrenia.

A combination of medication and psychosocial interventions is generall used to treat schizoaffective disorder. Medications include antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and antidepressants. The effectiveness of psychosocial interventions has been researched less for schizoaffective disorder than for schizophrenia or mood disorders. However, the evidence suggests that beneficial treatments include cognitive-behavioral therapy, social skills training, vocational rehabilitation, family therapy, and case management.

The bipolar subtype of schizoaffective disorder has a better prognosis than the depressive subtype. Everyone responds to treatment differently. While a brief period of treatment can provide effective relief with a return to normal functioning for one person, another person may require ongoing long-term treatment.

The term psychotic applied in the description, refers to symptoms that indicate an impairment in the patient’s ability to comprehend reality.

This includes delusions—beliefs that have no basis in reality and that are not susceptible to corrective feedback, and hallucinations—sensory perceptions that have no identifiable external source.

Symptoms

- Delusions

Delusions are the primary example of abnormal thought content in schizophrenia.

Delusional beliefs conflict with reality and are tenaciously held, despite evidence to the contrary. Delusions consist in several forms.

- Delusion of control is the belief that one is being manipulated by an external force, often a powerful individual or organization (e.g., the FBI) that has malevolent intent.

- Delusions of grandeur refers to patients’ beliefs that they are especially important and have unique qualities or powers (e.g., the capacity to influence weather conditions).

- In contrast, some patients express the conviction that they are victims of persecution or an organized plot, and these belies referred to as delusions of persecution.

- Thought broadcasting is a more specific form of delusion. It involves the patient’s belief that his or her thoughts are transmitted so that others know them.

- Finally, though withdrawal, is the belief that an external force has stolen one’s thoughts.

- Hallucinations

Hallucinations are among the most subjectively distressing symptoms experienced by schizophrenia patients.

These perceptual distortions vary among patients and can be auditory, visual, olfactory, gustatory, or tactile.

The majority of hallucinations are auditory in nature and typically involve voices. Examples include the patient hearing someone threatening or chastising him or her, a voice repeating the patient’s own thoughts, two or more voices arguing, and voices commenting.

The second most common form of hallucination is visual. Visual hallucinations often entail the perception of distortions in the physical environment, especially in the faces and bodies of other people.

Other perceptual distortions that are commonly reported by schizophrenics include feelng as if parts of the body are distorted in size or shape, feeling as if an object is closer or farther away than it actually is, feeling numbness, tingling, or burning, being hypersensitive to sensory stimuli, and perceiving objects as flat and colorless.

In addition to these distinctive perceptual abnormalities, persons suffering from schizophrenia often report difficulties in focusing their attention or sustaining concentration on a task.

It is important to note that in order for an unsubstantiated belief or sensory experience to qualify as a delusion or hallucination, the individual must experience it within a clear sensorium (e.g., unsubstantiated sensory experiences that occur only upon awaking from sleep or when falling asleep would not qualify as delusions).

Thus, for example, if a patient reports hearing something that sounds like voices when alone, but adds that s/he is certain that this is a misinterpretation of a sound, such as the wind blowing leaves, this would not constitute an auditory hallucination.

In addition to hallucinations and delusions, the DSM lists three other key symptoms of schizophrenia: disorganized speech, disorganized or catatonic behavior, and negative symptoms.

Disorganized Speech

The DSM uses the term disorganized speech to refer to abnormalities in the form or content of the individual’s verbalizations.

It is assumed that these abnormalities reflect underlying distortions in the patient’s thought processes. Thus the term thought disorder is frequently used by researchers and practitioners to refer to the disorganized speech that often occurs in schizophrenia.

Problems in the form of speech are reflected in abnormalities in the organization and coherent expression of ideas to others.

Incoherent speech, one common form of abnormality, is characterized by seemingly unrelated images or fragments of thoughts that are incomprehensible to the listener.

The term loose association refers to the tendency to abruptly shift to a topic that has no apparent association with the previous topic. In general, the overall content of loosely associated speech may be easier to comprehend than incoherent speech.

In pervasive speech, words, ideas, or both are continuously repeated, as if the patient is unable to shift to another idea. Clang association is the utterance of rhyming words that follow each other (e.g., “a right, bright kite”). Patients choose words for their similarity in sound rather than their syntax, often producing a string of rhyming words.

Disorganized or Catatonic Behavior

The overt behavioral symptoms of schizophrenia fall in two general areas: motor functions and interpersonal behavior.

Motor abnormalities, including mannerisms, stereotyped movements and unusual posture, are common among schizophrenia patients.

Other common signs include bizarre facial expressions, such as repeated grimacing or staring, and repeated peculiar gestures that often involve complex behavioral sequences.

As with other symptoms of the psychosis, the manifestation of motor abnormalities varies among individuals. Schizophrenia patients sometime mimic the behavior of others, a phenomenon known as echopraxia, or repeat their own movements, known as stereotyped behaviors.

Although a subgroup of patients demonstrate heightened levels of activity, including motoric excitement (e.g., agitation or failing of the limbs), others suffer from a reduction of movement.

At the latter extreme, some exhibit catatonic immobility and assume unusual postures that may also demonstrate waxy flexibility, a condition in which patients do not resist being placed into strange positions that they then maintain.

Course

For about one third of patients, the illness is chronic and is characterized by episodes of severe symptoms with intermittent periods when the symptoms subside but do not disappear.

For others, there are multiple episodes with periods of substantial symptom remission. About one third of those who receive the diagnosis eventually show a partial or complete recovery after one or two episodes.

Several factors have been linked with a more favorable prognosis for schizophrenia. Early treatment seems to be important in that the shorter the period between the onset of the patient’s symptoms and the first prescribed medication, the better the clinical outcome. Another indicator of better prognosis is a high level of occupational and interpersonal functioning in the primordial period.

Life Functioning and Prognosis

Before the introduction of antipsychotic medications in 1950, the majority of patients spent most of their lives in institutional settings. There was little in the way of programs for rehabilitation. But contemporary, multifaceted treatment approaches have made it possible for most patients to live in community settings.

Of course, during active episodes of the illness, schizophrenia patients are usually seriously functionally impaired. They are typically unable to work or maintain a social network, and often require hospitalization.

Even when in remission, some patients find it challenging to hold a job or to be self-sufficient. This is partially due to residual symptoms, as well as to the interruptions in educational attainment and occupational progress that result from the illness.

However, there are many patients who are able to lead productive lives, hold stable jobs, and raise families. With the development of greater community awareness of mental illness, some of the stigma that kept patients from pursuing work or an education has diminished.

Treatment and Therapy

- Antipsychotic Medication

Introduced in the 1950s, antipsychotic medication has since become the most effective and widely used treatment for schizophrenia. Research indicated that the “typical” antipsychotics, such as haloperidol, decreased the symptoms of schizophrenia, especially positive symptoms, and reduced the risk of relapse. However, they were not as effective in reducing the negative symptoms.

Chlorpromazine (Thorazine) was among the first antipsychotic commonly used to treat schizophrenia. Since the 1950s, many other antipsychotic drugs have been introduced.

Like chlorpromazine, these drugs reduce hallucinations, delusions, and thought disorder, and engender more calm, manageable, and socially appropriate behavior. As mentioned, all currently used antipsychotic drugs block dopamine neurotransmission. Thus it has been assumed that their efficacy is due to their capacity to reduce the overactivation of dopamine pathways in the brain.

Unfortunately, the benefits of standard or typical antipsychotic drugs are often mitigated by side effects. Minor side effects include sensitivity to light, dryness of mouth, and drowsiness. The more severe effects are psychomotor dysfunction, skin discoloration, visual impairment, and tardive dyskinesia (an involuntary movement disorder that can appear after prolonged use of antipsycotics).

Within the past decade, some new, “atypical” antipsychotic drugs have been introduced. It was hoped that these drugs would be effective in treating patients who had not responded to standard antipsychotics.

One example is Clozapine, released in 1990, which seems to reduce negative symptoms more effectively than typical antipsychotic drugs.

Clozapine not only offers hope for patients who are nonresponsive to other medications, but it also has fewer side effects than typical antipsychotics. However, clozapine can produce one rare, but potentially fatal, side effect, granulocytosis, a blood disorder.

Consequently, patients who are on this medication must be monitored on a regular basis. It is fortunate that several other new antipsychotic medications have recently become available, and some of these appear to have no serious side effects.

It is important to begin pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia as soon as possible after the symptoms are recognized. The longer patients go without treatment of illness episodes, the worse the long-term prognosis.

Medication also has the benefit of lowering the rate of mortality, particularly suicide, among schizophrenia patients. Patients who are treated with antipsychotic medication generally require maintenance of the medication to obtain continued relief from symptoms. Medical withdrawal often results in relapse.

Many schizophrenia patients also suffer from depression and, as noted, are at elevated risk for suicide. The reason(s) for the high rate of co-occurrence of depression with schizophrenia is not known.

Given the debilitating and potentially chronic nature of schizophrenia, however, it is likely that some patients experience depressive symptoms in response to their condition.

For others, depressive symptoms may be medication side effects or a manifestation of a biologically based vulnerability to depression.

- Psychological Treatment

Clinicians have used various forms of psychological therapy in an effort to treat schizophrenia patients.

Early attempts to provide therapy for schizophrenia patients relied on insight-oriented or psychodynamic techniques.

The chief goal was to foster introspection and self-understanding in patients. Research findings provided no support for the efficacy of these therapies in the treatment of schizophrenia.

It has been shown, however, that supportive therapy can be a useful adjunct to medication in the treatment of patients.

Similarly, psychoeducational approaches that emphasize providing information about symptom management have proven effective in reducing relapse.

Among the most beneficial forms of psychological treatment is behavioral therapy.

Some psychiatric hospitals have established programs in which patients earn credits or “tokens” for appropriate behavior and then redeem these items for privileges or tangible rewards.

These programs can increase punctuality, hygiene, and other socially acceptable behaviors in patients. In recent years, family therapy has become a standard component of the treatment of schizophrenia.

These family therapy sessions are psychoeducational in nature and are intended to provide the family with support, information about schizophrenia, and constructive guidance in dealing with the illness in a family member. In this way, family members become a part of the treatment process and learn new ways to help their loved cope with schizophrenia.

Another critical component of effective treatment is the provision of rehabilitative services. These services take the form of structured residential settings, independent life-skills training, and vocational programs. Such programs often play a major role in helping patients recover from their illness.

Summary

At present, it is firmly established that schizophrenia is caused by an abnormality of brain function that in most cases has its origin in early brain insults, inherited vulnerabilities, or both.

But the identification of the causal agents and the specific neural substrates responsible for schizophrenia must await the findings of future research.

There is reason to be optimistic about future research progress. New technologies are available for examining brain structure and function.

In addition, dramatic advances in neuroscience have expanded our understanding of the brain and the impact of brain abnormalities on behavior.

It is hoped that advances will also be made in the in the treatment of schizophrenia. New drugs are being developed at a rapid pace, and more effective medications are likely to result.

At the same time, advocacy efforts on the part of patients and their families have resulted in improvements in services. But a further expansion of services is greatly needed to provide patients with the structured living situations and work environments they need to make the transition into independent community living.

- Breier, A. (Ed.). (1996). The new pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press.

- Keefe, R. S., & Harvey, P. (1994). Understanding schizophrenia: A guide to the new research on causes and treatment. New York: Free Press.

- Miller, G. A. (Ed.). (1995). The behavioral high-risk paradigm in psychopathology. New York: Springer.

- Shriqui, C. L., & Nasrallah, H. A. (Eds.). (1995). Contemporary issues in the treatment of schizophrenia. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press.

- Torrey, E. F. (1994). Schizophrenia and manic-depressive disorder: The biological roots of mental illness as revealed by the landmark study of identical twins. New York: Basic Books.

- Walker, E. F. (1991). Schizophrenia: A life-course developmental perspective. New York: Academic Press.