Supply Chain Management

The function of supply chain management is to plan, organize, and optimize the various activities performed along the supply chainOpens in new window. Like other functional areas, supply chain management uses information systems. |

The goal of supply chain management (SCM) systems is to reduce the problems, or friction, along the supply chain. Friction can involve increased time, costs, and inventories as well as decreased customer satisfaction.

SCM systems, therefore, reduce uncertainty and risks by decreasing inventory levelsOpens in new window and cycle time while improving business processesOpens in new window and customer serviceOpens in new window. All of these benefits make the organization more profitable and competitive.

Significantly, SCM systems are a type of interorganizational information system.

In an interorganizational information system (IOS), information flows among two or more organizations. By connecting the information systems of business partners, IOSs enable the partners to perform a number of tasks:

|

The Push Model versus the Pull Model

Many supply chain management systems use the push model. In the push model, also known as make-to-stock, the production process begins with a forecast, which is simply an educated guess as to customer demand.

The forecast must predict which products customers will want as well as the quantity of each product. The company then produces the amount of products in the forecast, typically by using mass production, and sells, or “pushes,” those products to consumers.

Unfortunately, these forecasts are often incorrect. Consider, for example, an automobile manufacturer that wants to produce a new car. Marketing managers conduct extensive research, including customer surveys and analyses of competitors’ cars, and then provide the results to forecasters.

If the forecasters’ predictions are too high — that is, if they predict that a certain number of the new car will be sold, but actual customer demand falls below this amount — then the automaker has excess cars in inventory and will incur large carrying costs. Further, the company will probably have to sell the excess cars at a discount.

From the opposite perspective, if the forecasters’ predictions are too low — that is, they predict that so many new cars will be sold, but the actual customer demand turns out to be more than this number — the automaker probably will have to run extra shifts to meet the demand and thus will incur large overtime costs. Further, the company risks losing business to competitors if the car that customers want is not available. Using the push model in supply chain management can cause problems, as you will see in the next section (heading).

To avoid the uncertainties associated with the push model, many companies now employ the pull model of supply chain management, using web-enabled information flows.

In the pull model, also known as make-to-order, the production process begins with a customer order. Therefore, companies make only what customers want, a process closely aligned with mass customizationOpens in new window.

A prominent example of a company that uses the pull model is Dell ComputerOpens in new window.

Dell’s production process begins with a customer order. This order not only specifies the type of computer the customer wants, but it also alerts each DellOpens in new window supplier as to the parts of the order for which that supplier is responsible. That way, Dell’s suppliers ship only the parts Dell needs to produce the computer. |

Not all companies can use the pull model. Automobiles, for example, are far more complicated and more expensive to manufacture than are computers, so automobile companies require longer lead times to produce new models. Automobile companies do use the pull model, but only for specific automobiles that some customers order.

Problems along the Supply Chain

As you saw earlier, friction can develop within a supply chain. One major consequence of ineffective supply chain is poor customer serviceOpens in new window.

|

The problems along the supply chain arise primarily from two sources:

- uncertainties,

- the need to coordinate multiple activities, internal units, and business partners.

A major source of supply chain uncertainties is the demand forecast. Demand for a product can be influenced by numerous factors such as competition, prices, weather conditions, technological developments, overall economic conditions, and customers’ general confidence.

Another uncertainty is delivery times, which depend on factors ranging from production machine failures to road construction and traffic jams. In addition, quality problems in materials and parts can create production delays, which also generate supply chain problems.

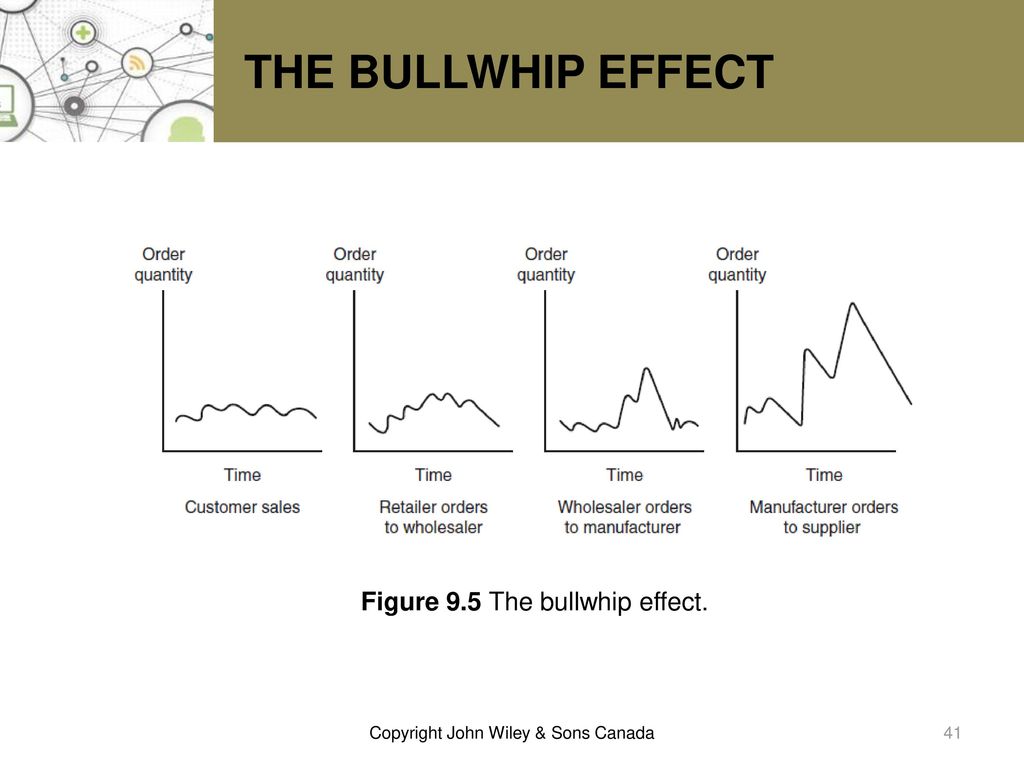

One major challenge that managers face in setting accurate inventory levels throughout the supply chain is known as the bullwhip effect.

The bullwhip effect is erratic shifts in orders up and down the supply chain (see the Figure below).

Source: The Internet

Source: The Internet

|

Basically, the variables that affect customer demand can become magnified when viewed through the eyes of managers at each link in the supply chain. If each distinct entity that makes ordering and inventory decisions places its interests above those of the chain, then stockpiling can occur at as many as seven or eight locations along the chain.

Research has shown that in some cases such hoarding has led to as much as 100-day supply of inventory that is waiting “just in case,” versus the 10- to 20-day supply at hand under normal circumstances.

Solutions to Supply Chain Problems

Supply chain problems can be very costly. Therefore, organizations are motivated to find innovative solutions. During the oil crises of the 1970s, for example, Ryder Systems, a large trucking company, purchases a refinery to control the upstream part of the supply chain and to ensure sufficient gasoline for its trucks. Ryder’s decision to purchase a refinery is an example of vertical integration.

Vertical integration is a business strategy in which a company purchases its upstream suppliers to ensure that its essential supplies are available as soon as they are needed.

Ryder later sold the refinery because it could manage a business it did not understand and because oil became more plentiful.

Ryder’s decision to vertically integrate was not the best method for managing its supply chain. In the remainder of this section, you will look at some other possible solutions to supply chain problems, many of which are supported by IT.

- Using Inventories to Solve Supply Chain Problems.

Undoubtedly, the most common solution to supply chain problems is building inventories as insurance against supply chain uncertainties. As you have learned, costs are associated with holding too much inventory. Thus, companies strive to optimize and control inventories with the support of information technologyOpens in new window.

For example, Loblaw CompaniesOpens in new window Limited implemented a warehouse management system to get all of its 25 distribution centers across Canada operating on one system and to standardize the processes of transferring merchandize from suppliers to distribution centers and from distribution centers to its grocery stores. This resulted in a reduction in inventory and increased inventory turnover, resulting in savings of up to $5 million annually and bringing fresher products to store shelves.

A well-known initiative to optimize and control inventories is the just-in-time (JIT) inventory system, which attempts to minimize inventories. That is, in a manufacturing process, JIT systemsOpens in new window deliver the precise number of parts, called work-in-process inventory, to be assembled into a finished product at precisely the right time.

Although JITOpens in new window offers many benefits, it has certain drawbacks as well. To begin with, suppliers are expected to respond instantaneously to requests. As a result, they have to carry more inventory than they otherwise would.

The inventory has not gone away in JIT; rather, it has just shifted from customer to supplier. This process can improve inventory size overall if the supplier can spread the increased inventory over several customers, but that is not always possible.

In addition, JIT replaces a few large supply shipments with a large number of smaller ones. This means that the process is less efficient in terms of transportation.

- Information Sharing

Another common way to solve supply chain problems, and especially to improve demand forecasts, is sharing information along the supply chain. Information sharing can be facilitated by electronic data interchange and extranets, topics you will learn about in the next webpage.

One notable example of information sharing occurs between large manufacturers and retailers. For example, WalmartOpens in new window provides Procter & GambleOpens in new window with access to daily sales information from every store for every item that P&G Opens in new window makes for WalmartOpens in new window. This access enables P&G to manage the inventory replenishment for Walmart’s stores.

By monitoring inventory levels, P&G knows when inventories fall below the threshold for each product at any Walmart store. These data trigger an immediate shipment. Information sharing between Walmart and P&G is executed automatically. It is part of a vendor-managed inventory strategy.

Vendor-managed inventory (VMI) occurs when the supplier, rather than the retailer, manages the entire inventory process for a particular product or group of products.

Significantly, P&G has similar agreements with other major retailers. The benefit for P&G is accurate and timely information on consumer demand for its products. Thus, P&G can plan production more accurately, minimizing the bullwhip effect.

See also:

- Bechtel C, Jayaram J (1997) Supply chain management: a strategic perspective. Int J Logistics Manag 8 – 1:15 – 34.

- Ballou R (1992) Business logistics management, 3rd edn. Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River BCG (2010) Rethinking operations for a two-speed world, Special Report, Boston Consulting Group.

- Vonderembsea M, Uppalb M, Huange S, Dismukes J (2006) Designing supply chains: towards theory development. Int J Prod Econ 100:223–238

- Vollman T, Berry W, Whybark C, Jacobs R (2005) Manufacturing planning and control systems for supply chain management, 5th edn. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Graphics courtesy of

Graphics courtesy of