Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

What Is Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy?

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is actually a number of related therapies that focus on cognition as the mediator of psychological distress and dysfunction.

As the name implies, CBT draws on and combines the theoretical and practical approaches of behavior therapy, dating to the 1950s, and cognitive therapy, dating to the 1960s work of Beck and Ellis (Ledley, Marx, & Heimberg, 2005).

Behavior therapy, as developed in the United States from the work of Skinner, redefined various mental illnesses as behavioral problems, hypothesized to have arisen from faulty learning.

The greatest progress achieved in behavior therapy came in reducing anxiety disorders and childhood disorders, such as aggressive and oppositional behavior, and in improving the quality of life for people with mental disabilities.

Whereas behavior therapy is based on various theories of learning, cognitive therapy is based on the assumption that emotional and behavioral disturbances do not arise directly in response to an experience but from the activation of maladaptive beliefs in response to an experience.

Treatment from a cognitive perspective then is directed at identifying and changing maladaptive cognitions, attributions, and beliefs that in turn affect emotional, physiological, and behavioral responses (Ledley, Marx, & Heimberg, 2005).

Before moving ahead to outline the basic concepts and applications of CBT, we present a case study that will be used throughout this literature to illustrate various aspects of CBT.

| CASE STUDY |

|---|

|

John, a 38-year-old European American man, sought therapy at his wife’s urging. He explained that he has worked for 15 years in the office supply business and recently received a significant promotion to a managerial position. Since receiving the promotion, he has become “extremely worried” that he will fail in his new role. His anxiety is interfering at work where he thinks that he “can’t do anything right.” He is particularly worried about his performance on various reports that he is responsible for completing. In spite of his efforts to get it right, minor corrections by his supervisor have been necessary on two occasions. He worries that he will lose his job and become unable to support to his family if this continues. At home, John’s anxiety is interfering in his relationship with his wife, who has told him that she is irritated by his absence while he works long hours. She has also complained that when he is home, he is “off in his own world fretting.” John wishes his wife would be less critical about his need to work longer hours and spend a lot of time thinking about work. He also worries, however, that he may be “a lousy husband and father”—just like he always feared. He describes a history of anxiety, particularly about work matters, with the current level of anxiety higher than at any previous time. Exploration of early history reveals that John was raised in an intact family in the rural Midwest. He describes his mother as “loving, but always trying to please my father.” He describes his father as “mean-spirited and never satisfied with anything, no matter how much I tried.” John would like to be less worried and feel better about his relationship with his wife. |

Basic Concepts of CBT

Three elements of cognition are important when assessing and treating various emotional and behavioral disorders, the first being the actual content of thoughts. We are most aware of the content of automatic thoughts; these are thoughts that come into our minds immediately as life unfolds.

More hidden from our awareness are thoughts that are referred to as rules or assumptions; these are thoughts through which we interpret our experiences. For example, John may automatically think, “I can’t handle this situation” on receiving critical feedback at work. If he were able to identify a rule related to the situation, it might be “I must be perfect at everything I do.” |

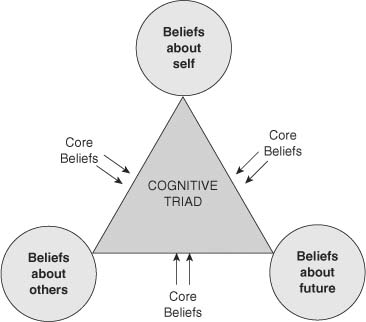

Specifically, clients’ perceptions of themselves, the world, and the future are key variables among emotional and behavioral disorders (Reinecke & Freeman, 2003).

Like John, those with anxiety may view themselves as incapable, the world as threatening, and the future as holding great risk of danger. Also considered important for cognitive therapy are meta-cognitions, or thoughts about cognitive processesOpens in new window. For example, John believes that he has a “need to spend a lot of time thinking about work,” potentially indicating a belief that it is helpful to worry about the potential threat of losing his job.

The second area of cognitive focus involves core beliefs.

Core beliefs are global, durable beliefs about the self and the world that are formed through early life experiences. They are maintained through a process of attending to information that supports the belief while disregarding information that is contrary to it (Beck, 1995).

As a child, John experienced intense criticism from his father and seems to have formed a core belief such as “I am totally inadequate.”

As an adult, he seems to ignore his history of career successes and instead focuses on the few moments in his day in which he has made a mistake or was unsure of himself. At home, he focuses on his wife’s current irritation and discounts a 14-year history of marriage that has been “mostly good for both of us.”

The third element of cognition involves maladaptive and ingrained styles of processing information, or cognitive distortions.

There are many types of distortions (Beck, 1995; MacLaren & Freeman, 2007), a few of which follow, with examples that might be seen in John, who perceives himself as inadequate.

|

Many emotional and behavioral disorders have been characterized by specific cognitive content, schema, and information processing styles (Reinecke & Freeman, 2003).

As already mentioned, those with anxiety disorders perceive themselves as inadequate and the world as dangerous and threatening. Regarding information processing, those with anxiety pay greater attention to anxiety-provoking stimuli than they do to neutral stimuli.

In panic disorder, the attentional bias is toward bodily sensation, with sufferers more acutely aware of their heart rates than other people. People with social phobia, on the other hand, attend to and make negative evaluations of their own social behavior.

DepressionOpens in new window also has been specified in terms of cognitive content and processing styles. Those who are depressed have a negative view of the self, the world, and the future (Beck, 1995).

For example, someone who is depressed may think, “I never do anything right; people are never there for me; and moreover, things will never get better.” Core beliefs are most often related to perceptions of self-defect, and attention is directed to experiences that focus on loss and failure (Reinecke & Freeman, 2003).

Practitioners of CBT employ understanding of the elements of cognition and their relation to specific disorders, as described previously, in a therapeutic relationship with well-specified roles for both the practitioner and the client.

The hallmark of the therapeutic relationship in CBT is collaboration, and roles of both the client and the practitioner are active. The role of the practitioner most closely resembles that of a supportive teacher or guide who holds expertise in cognitive and behavioral therapeutic methods, as well as possesses interpersonal skills (Ledley, Marx, & Heimberg, 2005).

The practitioner helps the client learn to identify, examine, and alter maladaptive thoughts and beliefs and increase coping skills. Although the practitioner lends methodological expertise, the client is the source of information and expertise about his or her own idiosyncratic beliefs that are significant to the client’s wellbeing.

Successful replacement of maladaptive cognitions depends on collaboration between client and practitioner, for the client can provide the most lasting and effective cognitive replacements.

Applications of CBT

The most prominent models of CBT are Beck’s cognitive therapy (Beck, 1995), Meichenbaum’s cognitive behavior therapy (Meichenbaum, 1994) and Ellis’s rational emotive behavior therapy (Ellis, 1996).

Although there are differences among them related to, for instance, the therapist’s level of direction and confrontation, all of the models share basic elements. All rely on identifying the content of cognitionsOpens in new window, including assumptions, beliefs, experiences, self-talk, or attributions.

Through various techniques, the cognitions are then examined to determine their current effects on the client’s emotions and behavior. Some models also include exploration of the development of the cognitions to promote self-understanding. This is followed with use of techniques that encourage the client to adopt alternative and more adaptive cognitions.

The replacement cognitions in turn, produce positive affective and behavioral changes. Other similarities of the models include the use of behavioral techniques, the time-limited nature of the interventions, and the educative component of treatment.

It is useful to consider the application of CBT in steps. At each step, a great number of specific techniques are available. Only a few are reviewed here due to space limitations.

- Assessment

As in many clinical work assessment processes, cognitive-behavioral assessments may result in a case formulation that includes psychiatric diagnosis; definition of the client’s problem in terms of duration, frequency, intensity, and situational circumstances; description of client’s strengths; and treatment plan.

Cognitive analysis of a client’s problem, however, is unique to cognitive-behavioral assessments. Assessment and case formulation includes many of the above-mentioned items, plus a prioritized problem list and working hypothesis that provide a cognitive analysis of the problems (Ledley, Marx, & Heimberg, 2005).

Problems are described very briefly and are accompanied by the client’s related thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. The working hypothesis, unique to each client, proposes specific thoughts and underlying beliefs that have been precipitated by the client’s current experiences. Formulations may also include an examination of the origin of the maladaptive cognitions and information processing style in the client’s early life. The working hypothesis is then directly related to treatment planning.

The following model, based on and adapted from Beck (1995), shows the relationship of John’s problematic thoughts, feelings, and behaviors to his situation at work.

Beck's cognitive triad | Source: Sage Opens in new window

Beck's cognitive triad | Source: Sage Opens in new window

|

|

- Teaching the Client the ABC Model

Concurrent with assessment, one of the first tasks of the cognitive-behavioral therapist is to educate the client about the relationship of thoughts, emotions, and behaviors.

Leahy (2003) suggests contrasting the client’s usual way of describing the relationship of thoughts, emotions, and behaviors with the alternative ABC model.

For most people, the usual way to think about it is that an activating event (A) causes an emotional or behavioral consequences (C). For example, John states that because he received criticism on his report (A), he is feeling anxious (C).

The ABC model proposes that in actuality, a thought or image representing a belief or attitude (B) intervenes between A and C.

Using the same example, following the criticism (A), John may think that he will lose his job (B), resulting in anxiety (C). client’s need to become very familiar with the model through presentation of and practice with personal illustrations.

- Teaching the Client to Identify Cognitions

Once the client understands the ABC model, the therapist helps him or her learn to identify thoughts and beliefs.

Clients may find that many types of cognitions are relevant for analysis, including those related to expectations, self-efficacyOpens in new window, self-conceptOpens in new window, attention, selective memory, attribution, evaluations, self-instruction, hidden directives, and explanatory style (McMullin, 2000).

A great variety of useful techniques for the purpose of identifying cognitions are described by McMullin (2000); DeRubeis, Tang, and Beck (2002); and Leahy (2003). The daily thought record is a written method involving a form made up of columns within which clients record activating events (column A), corresponding emotional reactions (column C), and immediate thoughts related to the event (column B).

In the case example, John would be taught to identify and record on the form an anxiety-provoking situation from the previous week, such as hearing from his boss that a report needed correction.

Next, he would be asked to identify his feelings when the situation occurred. Then he would be prompted to remember what went through his mind at the moment his boss spoke with him. In this instance, he would record his thought, “I can’t handle this” in between the situation and the anxious feelings.

Another method, the downward arrow technique, is a verbal way to discover the underlining meaning of conscious thoughts through the use of question such as, “What would it mean to you if the [thought] were true?”

Through the use of the downward arrow technique, the client may discover a core belief. John might provide an answer such as, “It would mean I’m incapable.” People are generally unaware of their core beliefs that are, nonetheless, very fundamental to the way they feel and behave.

- Teaching the Client to Examine and Replace the Maladaptive Cognitions

After identifying thoughts and beliefs, the client is ready to begin examining evidence for and against the cognitions. In addition, the client is encouraged to replace maladaptive cognitions with more realistic or positive ones.

Replacement requires frequent repetition and rehearsal of the new cognitions. Again, McMullin (2000), DeRubeis et al. (2001), and Leahy (2003) provide a wealth of information about specific techniques, a few of which are briefly described here.

Many of the techniques are verbal, relying on shifts in language to modify cognitions. In one technique, the client is taught to identify maladaptive thoughts as one of a list of cognitive distortions.

Cognitive distortions represent maladaptive thinking styles that commonly occur during highly aroused affective states, making logical thinking difficult. Identification of the use of a distortion allows for the possibility of substituting more rational thinking.

Though stopping, a behavioral means to draw attention to the need for substitution, might involve snapping an elastic band. Another technique involves the use of a variety of questions that provide opportunities to evaluate the truth, logic, or function of beliefs (Beck, 1995; Leahy, 2003). Such questions include:

|

Imagery and visualization are also used to promote cognitive change. For example, clients may be encouraged to visualize coping effectively in difficult situations or visualize an idealized future to provide insight into current goals.

McMullin (2000) suggests that imagery techniques are particularly useful to encourage perceptual shifts, whereas language techniques help facilitate change in more specific thoughts and beliefs. A combination of the two types of techniques is often useful.

- Other Techniques

Cognitive-behavioral therapists use a wide variety of behavioral techniques, according to the needs of the client. These include relaxation training, assertion training, problem solving, activity scheduling, and desensitization (Beck, 1995; MacLaren & Freeman, 2007).

Relaxation training probably would be useful for John.

|

In addition, cognitive-behavioral therapists often assign homework to their clients for the purpose of extending learning beyond the therapy session. Homework assignments vary according to the idiosyncratic needs of the client and generally are designed collaboratively. One common assignment is the use of a form such as the daily thought record.

- Beck, J. S. (1995). Cognitive therapy. New York: Guilford. DeRubeis, R. J., Tang, T. Z., & Beck, A. T. (2001). Cognitive therapy. In K. S. Dobson (Ed.), Handbook of cognitive-behavioral therapies, 2nd ed. (pp. 349 – 392). New York: Guilford.

- Ellis, A. (1996). Better, deeper, and more enduring brief therapy: The rational emotive behavior therapy approach. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

- Leahy, R. L. (2003). Cognitive therapy techniques: A practitioner’s guide. New York: Guilford.

- Ledley, D. R., Marx, B.P., & Heimberg, R. G. (2005). Making cognitive-behavioral therapy work. New York: Guilford.

- MacLaren, C., & Freeman, A. (2007). Cognitive behavior therapy model and techniques. In T. Ronen & A. Freeman (Eds.), Cognitive behavior therapy in clinical social work practice (pp. 25 – 44). New York: Springer.

- McMullin, R. E. (2000). The new handbook of cognitive therapy techniques. New York: Norton.

- Reinecke, M. A. & Freeman, A. (2003). Cognitive therapy. In A. S. Gurman & S. B. Messer (Eds.), Essential psychotherapies (pp. 224 – 271). New York: Guilford.

- Ronen, T., & Freeman, A. (Eds.), (2007). Cognitive behavior therapy in clinical social work practice. New York: Springer.