Memory

One may ask “Why do we forget lots of things, many of them things we didn’t want to forget? And what makes some things memorable, and others forgettable?”

This literature explores one of the core topics in cognitive psychology—human memory. Like the air we breathe, memory is quite important. Without it we would not recognize anyone or anything as familiar. We would not be able to talk, read, or write, because we would remember nothing about language. We would be like newborn babies.

We use memory for numerous purposes—to keep track of conversations, to remember telephone numbers while we dial them, to write essays in examinations, to make sense of what we read, and to recognize people’s faces.

There are many different kinds of memory, which suggests that we have a number of memory systems. This literature explores in detail the sub-divisions of human memory and begins with the curious question.

What is Memory?

Memory is the process of retaining information after the original thing is no longer present. Memory is the capacity to retain information over time, in other words. There are close links between learning and memory. Something that is learned is lodged in memory, and we can only remember things learned in the past.

Memory is the glue that holds our thoughts, impressions, and experiences. Without it, past and future meaning and self-awareness would be lost as well. Hans J. Markowitsch, 2000, p.257

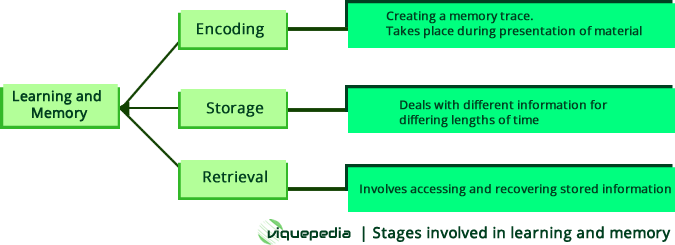

Memory and learning can most clearly be demonstrated by good performance on a memory test, such as giving someone a list of words for a specified period of time, removing the list, and later asking them to recall the list. When learning and memorizing the words in the list, there are three stages:

- Encoding

When humans are given the list they encode the words. They lodge the words in memory. Encoding means to put something into a code, in this case the code used to store it in memory—some kind of chemical memory trace. For example, if you hear the word Chair, you might encode it in terms of your favorite chair that you normally sit in at home. Your encoding of the word Chair involves converting or changing the word you hear into a meaningful form, in other words.

- Storage

As a result of encoding, the information is stored within the memory system. Some information remains stored in memory for decades or even an entire lifetime.

- Retrieval

Retrieval is the process of recovering stored information from the memory system. This is known as recall or remembering.

In a narrow sense, memory is the mental processes involved in encoding, storage, and retrieval of information. Encoding depends on which sense provides the input; storage is the information being held in memory; retrieval involves accessing the stored information.

Testing memory

| Psychologists use various methods to test recall or learning: |

|---|

|

Free recall —Give participants some words to learn and then ask them to recall the words in any order.

Cued recall —After presenting the material to be learned, provide cues to help recall. For example, saying that some of the items are minerals. Recognition —Giving a list of words which includes some of those in the initial presentation. Participants are asked to identify those in the original list. Paired-associate learning —Participants are given word pairs to learn and then tested by presenting one of the words and asking them to recall the other word. Nonsense syllables —Participants are asked to memorize meaningless sets of letters. These maybe trigrams (three letters). |

| Source: Michael W. Eysenck, Michael W. Eysenck.) |

Psychologists who are interested in learning focus on encoding and storage, whereas those interested in memory concentrate on retrieval. However, all these processes depend on each other. They work hand-in-hand, in other words.

Categories of Memory

Memories have been broken down into different unique categories or types, differing in their time-course, capacity, and the type of information processed. Distinctions between the various categories of memory arose from neuropsychological studies, often investigating brain lesions and amnesia Opens in new window (Squire, 1986).

There is distinction between declarative (or explicit) memory and non-declarative or implicit memory, which differ largely on the level of conscious awareness devoted to processing. Declarative memories Opens in new window are those for which we have conscious awareness, while non-declarative memories Opens in new window are acquired below such awareness (Schacter, 1987).

Further, declarative memories come in two types:

- episodic and

- semantic.

Episodic memories are those memories that concern specific life events or episodes, and contain temporal and spatial information, such as the memory of the details surrounding your first kiss.

Alternatively, semantic memories concern facts and general knowledge acquired throughout our lives, but lack distinct temporal or spatial information, such as knowing that the capital of France is Paris, but being unable to remember the exact event in which you learned this information (learn more here Opens in new window).

On the other hand, non-declarative memories encompass procedural memories Opens in new window, which include memories for performing skills that often cannot be verbally expressed, such as knowing how to ride a bike (learn more here Opens in new window).

A further distinction is that between neutral and emotional memories. Emotional memories Opens in new window are those that have an emotionally salient component, whether positive or negative (Hamann, 2001; Kensinger, 2009; learn more here Opens in new window).

There is a large body of research indicating that emotional saliency enhances memories (Lang, Dhillon, and Dong, 1995; Ochsner, 2000), and there has recently been increased attention paid to this fact within the sleep and memory literature, resulting in the conclusion that sleep Opens in new window selectively enhances memory for emotionally salient over neutral episodic information (Hu, Stylos-Allan, and Walker, 2006; Payne et al., 2008; Wagner, Gais, and Born, 2001).

These various types of memory are not only dissociated by the content or level of consciousness associated with them, but they can also be distinguished by the different neural systems that promote them. For instance, declarative memories Opens in new window rely heavily on the medial temporal lobe Opens in new window and the hippocampus Opens in new window (Moscovitch et al., 2005).

Evidence supporting this relationship comes from patients with selective hippocampal damage, such as the famous patient H.M. Opens in new window who could not form newo episodic memories Opens in new window due to the surgical removal of his bilateral hippocampus to control his severe epilepsy (Scoville an Milner, 1957). He could, however, form new procedural memories Opens in new window (Corking, 1968), which are supported by areas of the neocortex and subcortical structures such as the basal ganglia (Moscovitch et al., 2005).

Finally, there is evidence that emotional memories are supported by activation of the amygdala Opens in new window, a subcortical structure adjacent to the hippocampus that is important for processing emotion (Hamann, 2001; McGaugh, 2004). In fact, this close proximity to the hippocampus is believed to be a crucial factor for the effects of the amygdala on emotional memory formation, due to the ease with which these structures can interact (Hamann et al., 2002; Kensinger an Schacter, 2006). There is evidence that each type of memory is uniquely impacted by neural processing during sleep Opens in new window.

See also:

- Gais, S., and Born, J. (2004). Declarative memory consolidation: mechanisms acting during human sleep. Learning and Memory, 11 (6), 679-685. doi: 10.1101/lm.8054.

- Hamann, S. (2001). Cognitive and neural mechanisms of emotional memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 5 (9), 394-400. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01707-1.