Libido

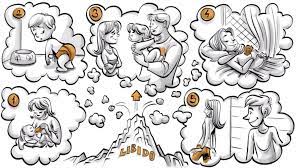

Graphics courtesy of Sprout SchoolsOpens in new window

Graphics courtesy of Sprout SchoolsOpens in new window

|

Sigmund Freud coined the term libido in the early 1900s. Libido means sensual desire or the drive for physical pleasure seeking. According to Freud, it is one of three primary motivational forces in people, along with the drive for self-preservation and a destructive drive.

Freud (1905/1953, 1916/1961, 1963/1997) famously and elaborately described the way that libido is linked to human psychological development. According to his theory of psychosexual developmentOpens in new window, children derive sensual pleasure from particular objects and activities during each of the stages of their psychological development.

The stages are named oral, anal, phallic, latency, and genital; each of these labels identifies the main area of the body around which pleasure is centered during that particular stage.

Latency refers to the idea that libido is repressed during this stage, and therefore pleasure is not centered around any part of the body at all.

For instance, in the first stage of development, the oral stage, the infant/young child’s pleasure is centered around oral activities: sucking, placing objects in the mouth, and so on.

A primary source of enjoyment is the mother’s breast. The child not only obtains pleasure from the object (in this case, the breast) but also develops a psychological attachment to the object from which it receives pleasure. These same principles of pleasure and attachment apply to the remaining stages (except latency).

The final stage, genital, is psychological maturity. According to Freud, if development has progressed adequately, the individual’s libido will be directed toward an opposite-sexed partner during this final stage. Like the other stages, pleasure and attraction are linked with attachment to the object (opposite-sexed partner); pleasure and love are linked. Put another way, according to Freud, sex and love are intimately associated with one another.

Freud (1963/1997) emphasized the role that sensual desire plays in mental illness, particularly neurosis, a large class of mental illnesses that are generally less severe than psychosis but that can involve significant suffering, for instance, depression and the wide variety of anxiety disorders.

In Freud’s theory, development has a goal, which is that the individual reach the genital stage, where the individual becomes capable of experiencing love toward, intimacy with, and desire for sexual activity with a hetero-sexual partner.

Freud went so far as to say that the most normal development in the genital stage is behavioral heterosexual monogamy (which does not mean that people do not have sexual desire outside of the monogamous bond but means that people, if they are psychologically strong, will tend to choose to behave within the bond).

According to Freud, this is the normal and ideal development because it ensures survival of the species. People will mate with someone with whom they can reproduce, an opposite-sexed partner. Furthermore, pair bonding is beneficial for one’s offspring and helps to keep societies stable.

Although the genital stage is the goal, most people do not arrive at the goal unscathed. Since libido involves both pleasure seeking and love/attachement, the potential exists for both frustration of pleasure and psychological hurt, for example, through feeling rejected by a loved object.

In the oral stage, for instance, the child may experience some extreme in breast feeding—overindulgence or deprivation—or the child may have had experiences with the mother that led to mistrust. Under these circumstances, the child will, to some extent, become “stuck” at that stage, leaving less energy (libido) for the child to direct toward the upcoming stages.

Freud said that libido is a fixed or limited amount of energy. If libido is directed in one direction (e.g., toward oral interests), there is less libido remaining for another direction (e.g., toward a heterosexual partner).

Being stuck at a stage is called a fixation. Fixations are sources of mental illness symptoms. For example, during the oral stage, an individual is passive and dependent. If the caretaker overindulges the child in regard to breast-feeding and other situations, the child may become fixated here, resulting in a number of possible outcomes such as passivity and dependency in adulthood, an eating disorder, oral behaviors such as smoking, and so forth.

Like so many of Freud’s theories, aspects of the libido theory have receided support and other aspects have not. For instance, many psychologists agree that pleasure seeking is a powerful motive for people (e.g., Skinner, 1938). However, whether pleasure seeking exists in exactly the way Freud most often presented it (almost exclusively sensual) is questionable. Additionally, the idea of whether pleasure-seeking energy is fixed is debatable. Scholars who were initially followers of Freud and who later broke off and developed independent theories, such as Carl Jung and Alfred Adler, revised the libido concept, viewing it as a general creative life force.

- Freud, S. (1953). The ego and the id. In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 19). London: Hogarth Press.

- Freud, S. (1997). Sexuality and the psychology of love. New York: Touchstone.

- Freud, S. (1953). Three essays on the theory of sexuality. In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 7, pp. 123 – 213). London: Hogarth Press.

- Freud, S. (1961, 1963). Introductory lectures on psychoanalysis. In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vols. 15 & 16). London: Hogarth Press.

- Freud, S. (1997). Sexuality and the psychology of love. New York: Touchstone.

- Skinner, B.F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. New York: Macmillan.