Mongolian Spot

Definition and Clinical Features

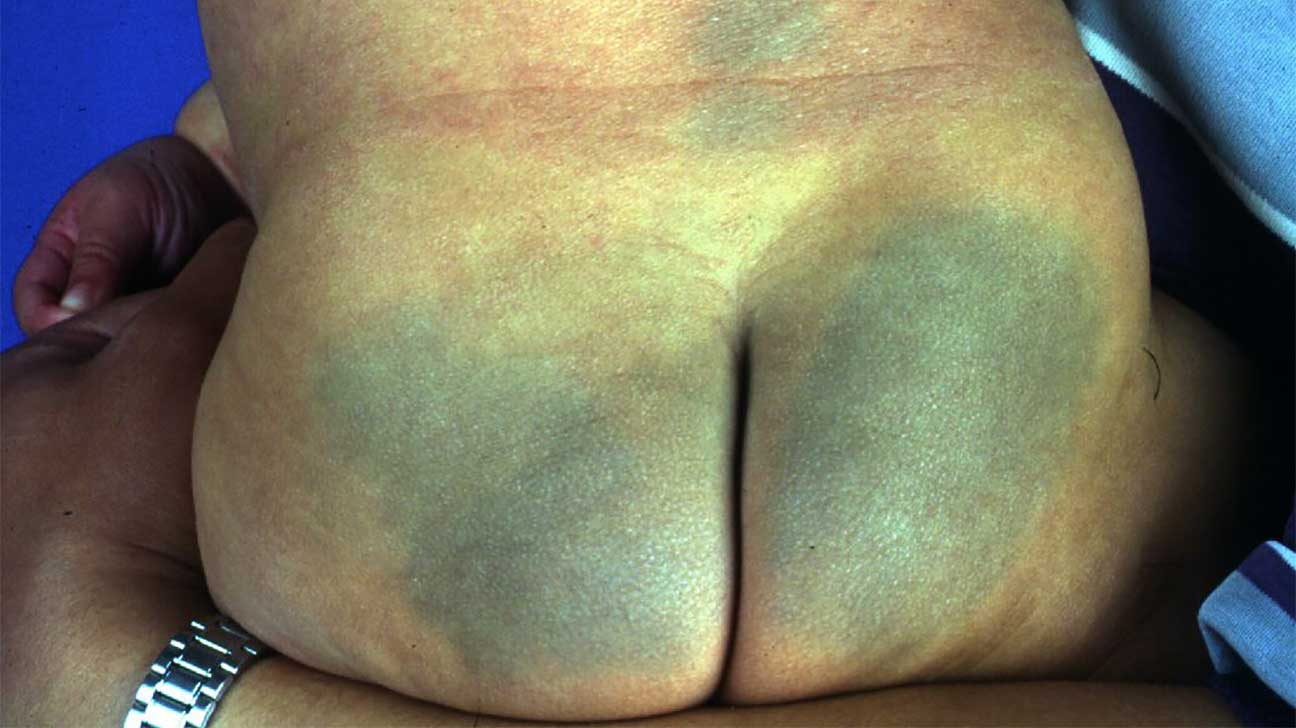

Photo courtesy of healthline Parenthood Opens in new window

Photo courtesy of healthline Parenthood Opens in new windowMongolian spots are flat, blue-gray or blue-green, often poorly circumscribed, large macular lesions generally located over the lumbosacral areas, buttocks, and over the shoulders.

Present at birth, Mongolian spots are seen occasionally on the lower anterior trunk and extremities of healthy infants; only rarely are they seen on the face.

The lesions may be single or multiple and vary in diameter from a few millimeters to 8 centimeters; they typically disappear spontaneously in early childhood or during adolescence. It is rarely seen in adults, but in some cases may persist for life.

Incidence and Prevalence

The occurrence of Mongolian spots has predilection for certain ethnic groups. Asian, southern European, American black, and Native American infants are particularly prone to Mongolian spots.

Statistically, more than 90% of African-American and Asians have Mongolian spots, whereas fewer than 10% of whites have them.

Infants of Hispanic and Mediterranean heritage are more likely to have the spots than are infants of northern European ancestry. The Mayan Indians uniquely take great pride in it as an indicator of pure Mayan inheritance.

In a study of Nigerian children, 369 neonates and 484 children aged 1 month to 14 years were evaluated for the presence of Mongolian spot.

The spots were present in over 381 children with an overall incidence of 44.7% (74.8% of neonates and 13.6% of pre-school children). There was no gender predilection.

Traces of Mongolian spots disappeared with advanced age and none were found in children over 6 years old. However, in some instances MS can persist for life.

Pathogenesis

Mongolian spot is a congenital, developmental condition exclusively involving the skin. It results from entrapment of melanocytes in the dermis during their migration from the neural crest into the epidermis.

Mongolian spots represent collections of spindle-shaped melanocytes located deep in the dermis, probably as the result of arrest during their embryonal migration from the neural crest to the epidermis.

The slate blue to blue-gray or blue-green color depends on the Tyndall effect (a phenomenon in which light passing through a turbid medium, such as the skin, is scattered as it strikes particles of melanin).

Long-wavelength light rays (red, orange, and yellow) tend to be less scattered and therefore continue to pass downward into the lower levels of the skin; colors of shorter wavelengths (blue, indigo, and violet) are scattered to the side and backward to the skin surface, thus creating the blue-green or slate gray discoloration.

Clinical Evaluation

Although Mongolian spots are typically benign blue-gray discolorations, extensive Mongolian spots can indicate possible inborn errors of metabolism.

There was a report of three infants with extensive Mongolian spot of whom two had GM1 gangliosidosis type 1 Opens in new window, and a third had an associated Hurler’s syndrome Opens in new window. It is therefore important to diagnose extensive Mongolian spots so that early treatment may be administered.

In another observational report from Northern Italy, 630 healthy neonates were examined to study birthmarks and transient cutaneous lesions in newborns of different ethnic groups.

Hyperpigmentation in the genital area and Mongolian spot were positively associated with geographical area of origin and were more common in non-European neonates.

There was a positive correlation between melanocytic congenital nevi Opens in new window in Asian newborns as well as a salmon patch Opens in new window on the nape of women who were greater than 35 years of age.

Diagnosis

Mongolian spots may easily be recognized by their characteristic blue-green or blue-black coloration, their common lumbosacral distribution, and their presence at birth.

Unlike bruises, Mongolian spots do not change in appearance over several days. Because Mongolian spots are benign, there are no complications associated with these lesions.

Therapeutic

Since MS are benign lesions which may rapidly disappear, therapy is not necessary. They most commonly fade within the first 4–5 years of life, but they persist into adulthood in approximately 5% of patients. However, large and numerous Mongolian spots may be seen in lysosomal storage disorders, among them GM1 gangliosidosis type 1, Hunter syndrome, and Hurler syndrome. In these children, the Mongolian spots often fade, but not until at least the 2nd decade of life. Large and extensive Mongolian spots can be seen with phakomatosis pigmentovascularis and phakomatosis pigmentopigmentalis, on association with vascular malformations and other pigmented lesions, respectively.

- Gupta D, Thappa DM. Mongolian spots – a prospective study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013; 30:683-8.

- Cordova A. The Mongolian spot: a study of ethnic differences and a literature review. Clin Pediatr (Philia). 1981;20:714-9.

- Chaithirayanon S, Chunharas A. A survey of birthmarks and cutaneous skin lesions in newborns. J Med Assoc Thai. 2013;96 Suppl 1:S49-53.

- Osburn K, Schosser RH, Everett MA. Congenital pigmented and vascular lesions in newborn infants. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987;16:788-792.

- Dungy CI. Mongolian spots, day care centers, and child abuse. Pediatrics 1982;69:672.