Social Network Analysis

Photo courtesy of ToolsheroOpens in new window

Photo courtesy of ToolsheroOpens in new windowSocial network analysis (SNA) is the process of investigating social structures through the use of network and graph theories. This process uses nodes (individual actors, people, or things) and the ties or edges (interactions) that connect them (Otte & Rousseau, 2002). |

Social network analysis is a valuable technique enabled by IT which can help managers learn about informal relationships and network structures within an organization. With SNA they can know has influence and who doesn’t, who people turn to for answers, who has the knowledge and technical capability to be innovative, and who has leadership potential.

SNA was developed by scientists as a social theory to diagram relationships among people that differ from the formal hierarchy.

A large petroleum organization conducted an SNA and found a striking difference between the formal structure defined by hierarchical reporting relationships and the way in which information actually flowed through the organization.

| IN PRACTICE | Exploration and Production Division |

|---|

| The deep-sea drilling industry is highly competitive and highly capital-intensive. Executives knew they could reap huge cost savings if every platform could drill as quickly and cost-efficiently as the company’s best. The question was whether people were effectively sharing knowledge and best practices. A first step in a social network analysis was to map the interactions for the top 20 executives in the Exploration and Production Division (E&PD). The results were surprising. The SNA revealed that in the informal information flow there was a complete separation with no communication between the Production Department and the Drilling Department, and only a single manager who linked the Production Department with the Exploration Department in the information flow. In other words, the actual information flow was not sufficient to meet the need for coordination. The mapping also found that the senior vice president was relatively peripheral to the flow of information. interviews with managers and further investigation provided insight into how the E&PD could more effectively manage the flow of information and knowledge-sharing. |

As the above IN PRACTICE example shows, the structure as defined by the informal information flow may be very different from the formal organization structure as defined by the hierarchy.

Roles in Social Networks

Social networks include people who turn to one another for help, advice, information, and support, whether or not they are in the same work group.

It is within these networks that much of an organization’s work gets done.

There is a secret structure at every organization that spells success or failure. You can’t see it in the org chart or in the flow of money on the spreadsheet. But within this [informal] structure, the assistant in the third cubicle from the elevator may be more crucial than the suit in the fancy corner office,” says corporate anthropologist Karen Stephenson.

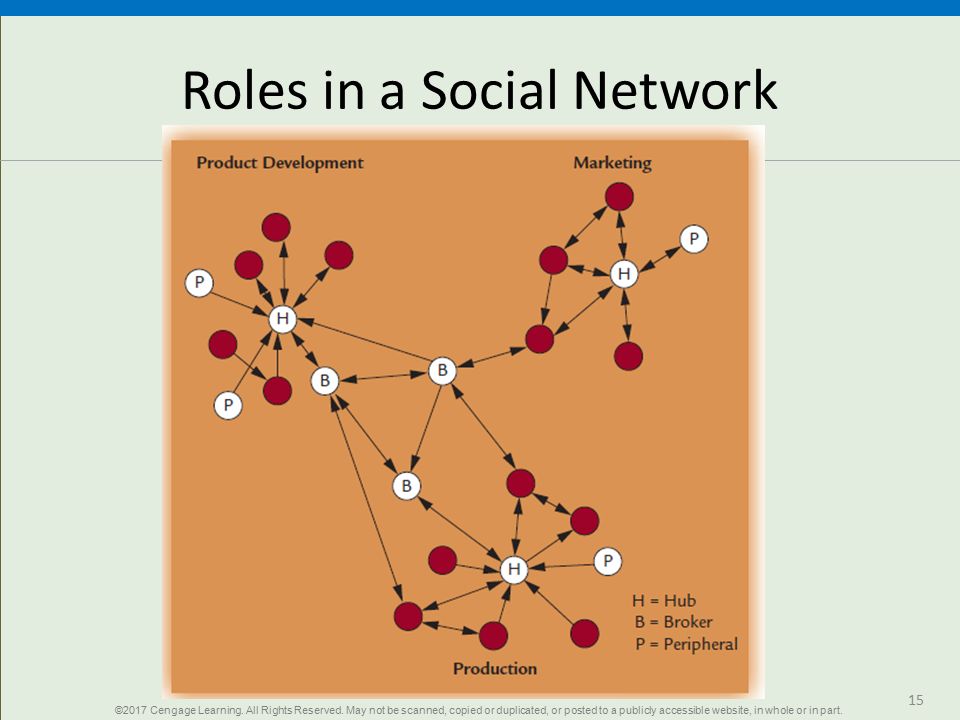

People play different roles in social networks. Three roles, or patterns of relationships, seen over and over in organizations are:

- the hub,

- the broker, and

- the peripheral player.

- Hubs

Hubs are people who are at the center of an information network. These are people who are sought out for their knowledge and information.

Hubs tend to have more influence than other employees. They may have technical expertise and organizational memory, as well as a set of relationships that helps them get information that other people need.

Hubs are the “go to” people in an organization. If they don’t know the answer, they know where to find it.

A long-time salesperson might be a hub because he or she has developed connections with other salespeople as well as with clients, managers, and people in other departments, and has years of knowledge about how the organization works.

- Peripheral Players

Peripheral players have the fewest number of connections and operate on the boundaries of a network. They are marginal players, but they can still be important because they may have niche expertise or valuable outside contacts. These might not be needed on a daily basis but could be useful during a crisis or for specialized projects.

- Brokers

Of particular importance are the brokers, the people who have a knack for connecting people across boundaries and subgroups.

Brokers link specialized pools of knowledge and integrate the larger network within the organization.

For example, a well-known investment bank won the business of a major account from a rival bank thanks to David Hawkins, a manager who played a broker role.

The client had been with the rival bank for years. However, Hawkins had connections to different product and service groups within his bank that the executive at the rival bank didn’t have within his firm.

Hawkins served as a link across his bank’s groups and introduced the client to them, which enabled his bank to create a more targeted and customized financial solution that met the client’s unique needs.

Figure X1 illustrates the three roles in a hypothetical organization, showing how the broker connects different parts of the larger network.

Figure X1 Roles in a Social Network

Figure X1 Roles in a Social Network

|

Understanding these informal networks offers a competitive advantage to a company. By knowing who is facilitating high performance in others, who is collaborating, and who has personal connections, managers have a tool through which to help the company improve, innovate, expand, and grow.

SNA experts work with companies to find their hidden networks by asking employees simple questions like the following:

- ”To whom do you go for a quick decision?”

- ”Whom do you hang out with socially?”

- ”To whom do you turn for advice?”

- “Whom do you go to with a good idea?”

- “To whom do you go for career advice?”

SNA can be administered in the form of an electronic survey or by tracking e-mail messages among employees. Here are some examples of information that a sophisticated network tracking system might provide:

- Who is working with whom in the company’s social network?

- Who are the informal leaders, and who has leadership potential?

- How does knowledge and information flow through an organization?

- Who is being overutilized, and who is being underutilized?

- Who are the experts in a company before they retire so their knowledge can be stored or transferred?

Social network analysis can uncover hidden workplace relationships. It offers clear delineation of relationships through data, facts, and statistics instead of relying on rumor and innuendo. These data can be used to change the organization.

For example, after reviewing the results of the SNA, the packaged food company MarsOpens in new window found that people in the snack food division in New Jersey weren’t talking enough with peers in the Los Angeles food division, creating duplication of work and missing opportunities for collaboration and information sharing.

Now MarsOpens in new window builds in ways for colleagues on both coasts to keep in touch with each other, and their performance reviews are based in part on their informal networking activities.

Sometimes a stronger intervention is needed to change networking patterns. A global consulting organization discovered that two subgroups had formed based on technical and nontechnical skills.

Clients needed a combination of “soft” strategy and organizational design smarts combined with “harder” technical knowledge. The split between the two groups came about because individuals gravitated toward each other based on common work-related and professional interests, attending the same conferences, and time spent working together.

With guidance from management, each subgroup learned what the other group offered to clients. The groups were brought together to discuss the situation, which ultimately led to changes in how the groups operated. These changes promoted knowledge sharing and collaboration.

The final result of collaborative groups gave the consulting company a distinct advantage that resulted in more sales and happier clients. Systematic manager interventions based on SNA can help a company build a healthy pattern of informal relationships that replace ad hoc dysfunctional relationships.

Also in this series include:

- Richard L. Daft and Norman B. Macintosh, “The Nature and Use of Formal Control Systems for Management Control and Strategy Implementation,” Journal of Management 10 (1984), 43 – 66