Channels of Distribution

The Strategies of Channels of Distribution

Graphics courtesy of Corporate Finance Institute (CFI)Opens in new window

Graphics courtesy of Corporate Finance Institute (CFI)Opens in new window

Because consumer goods are readily available, we tend to forget that they have to go through a complex process before reaching the shop. Consider, for example, a simple can of Coca-Cola. It follows a channel before it eventually reaches you — the final consumer. This channel is termed a channel of distribution. |

What is a Channel of Distribution?

A channel of distribution is the route taken by a commodity (physical products) or service (intangible or even virtual products) from the point of manufacture through to final consumption.

There are many routes which a product can take to the customer. For example, the Coca-Cola drink mentioned earlier consists of raw materials (like cane sugar, caramel, and a syrup made from many other ingredients ) that must be sourced.

The syrup is then sent to the bottling plant, where it is added to purified water and then bottled or canned. From the bottling plant the goods are either transported to a warehouse for temporary storage, or they are sent straight to the wholesaler or retailer.

You, the customer, then purchase the bottle from the retailer. The goods have followed a channel of distribution before reaching you. They have moved through a supply chain, that is, certain items needed to be sourced before the final product was prepared.

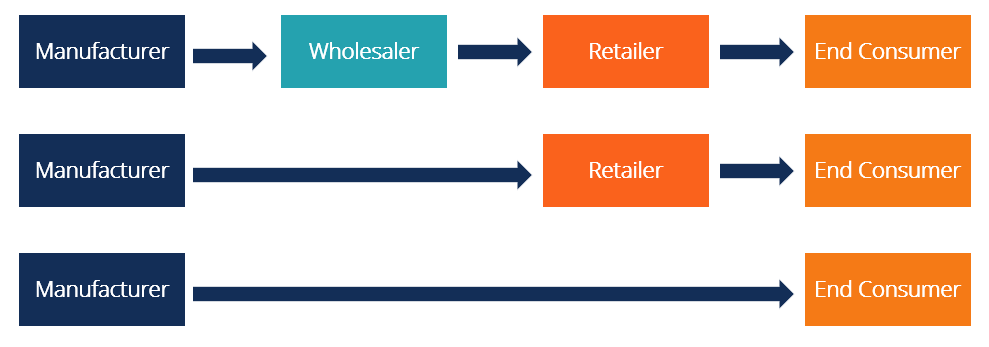

Some of the routes a product can take include the following:

|

Every product or service follows a channel of distribution. Channels can either be direct or indirect.

Direct Channel

A direct channel would be one which takes goods or services directly to the customer.

For example, the vegetables from your farm are bought by a passing traveler. The wooden curio produced in your hut is sold to the passing tourist.

Indirect Channel

An indirect channel is one which conveys goods to the customer via middlemen (intermediaries).

For example, a motor vehicle goes from the manufacturer to the dealership, and from the dealership to the customer. Or the can of Koo Peaches goes from the farm to the manufacturer to a wholesaler (trade center), from the wholesaler to the retailer (Pick ‘n Pay), and from the retailer to the customer (consumer).

Normally, the longer the channel, the more expensive the item becomes. For example, a simple men’s tie might be bought by an importer for around R10 from an Italian company like Fabios of Milan. It is then sold for R30 to the wholesaler, for R40 to the retailer, and then for R80 to the final customer. The complexity of the distribution required will affect whether one chooses to go to the customer directly or indirectly.

The Role of the Manufacturer in a Channel of Distribution

Channels of distribution develop when many exchanges take place between producers and final consumers. Manufacturing is the first major activity in a channel of distribution when a commodity (like Coca-Cola) is manufactured. But before it is manufactured, certain key items need to be sourced. This is the responsibility of the purchasing or procurement department.

Manufacturing depends on distribution for selling the item produced, transportingOpens in new window the item to the customer, warehousingOpens in new window the item once it is produced, and handling the product physically (you need the right forklift to load the produced motor vehicle).

What is wanted is the optimum performance of all these activities at the lowest possible cost (this is one of the primary goals of a logistician: to keep performance costs as low as possible).

Manufacturing must select the best channel structure for the movement of the product to the final customer (should we go to the customer directly or indirectly?), choose the best possible intermediaries and establish policies to govern the distribution, and develop an information control system to ensure that all channel objectives are met in terms of the volumes to be sold and the place of sale.

The Role of the Wholesaler in a Channel of Distribution

Once goods have been manufactured, they are transported to the wholesaler (in a traditional channel of distribution, although this is not necessarily the case). The wholesaler’s key goals are to establish solid relationships with manufacturers and retailers in terms of Just-in-Time manufacturingOpens in new window and movement of goods.

Progressive wholesalers bind the producer to the customer by providing certain value-added services (like fetching the goods produced), utilizing their customer base, breaking down bulk for the retailer, assembling or packaging goods for the retailer (for example, packets of nuts and screws for bicycle sellers) and other forms of value-added services.

In the new economy, wholesalers must offer a value-added function in order to survive. If they do not, they will become extinct like the dinosaur.

The Role of the Retailer in a Channel of Distribution

In a traditional supply chainOpens in new window, once goods have reached the wholesaler, they are purchased by the retailer (although many modern retailers often skip the wholesaler and receive the manufactured goods straight from the manufacturer). The smooth functioning of a retail business is critically dependent on the physical flow of goods from the manufacturer to the retailer. The location of a retail outlet is also critical for survival. A poor location will mean poor sales.

Distribution Decisions

All distribution decisions depend on the answers to one of these three questions:

- Where do we want our goods to be sold? (Place decisions.)

- How are we going to get them there? (Transport decisions.)

- Why do we want to use certain intermediaries (Marketing decisions.)

Certain key factors will influence our distribution decisions. These factors include:

- The nature of our target market.

Where do the customers live — are they urban or rural customers? If they are rural customers and they are buying our two-liter fruit juice, the handle on the packaging will be of critical importance.

- The nature of our product.

Is it big or small, expensive or inexpensive? For example, we might sell our fancy Lamborghini sports cars only through retailers like Investment Cars, an exclusive display house.

- Manufacturer’s concerns.

Certain manufacturers decide who they will use to distribute their product (and not vice versa). In South Africa, Bauer pans sell only through Game, Dions and approved Verimark dealerships.

- The nature of the competition.

Certain products may be sold at chosen outlets (like the Hyperama) to compete directly with other products.

- The intensity of the required distribution.

For example, if one wants the product to be sold everywhere, one is using an intensive distribution strategy. If one carefully selects a few chosen distributors (as Bauer did when they selected only Verimark, Game, Dions and other reputable retailers to sell their product), then one is using a selective distribution strategy.

If goods are sold only through exclusive retail outlets (for example, Rolex watches are available from only about five exclusive shops in Cape Town), then an exclusive distribution strategy is being used.

Why do Channels of Distribution Develop?

Channels of distribution develop for the following reasons.

- To increase the efficiency of movement of goods

Channels of distribution develop because they can increase efficiency as goods move from manufacturer to final consumer. This increased efficiency creates time, place and possession utility for the customer. But what does this mean? In lay-man’s terms, this means that customers will be able to buy their Coca-Cola at a time and place that suits them, and maybe even in a quantity that suits them (a two-ltr Coke, for example).

- Easier marketing

Channels of distribution make it easier to market and sell products. Customers know where to find products and services. They provide clarity in the mind of the customer as to where to go for certain products (If I need a Bic pen, I will go to the CNA).

- Reducing the complexity for the customer

Channels of distribution also reduce the complexity of buying for the customer. Where do you buy a Swatch watch? “Go to Truworths.” Customers want to be informed, in a simple a manner as possible, where to buy certain goods. Wise distributors know this and try to make things as simple as possible for the customer.

- Economies of scale

Channels of distribution enable one to sell more of a product. As goods are distributed and extended through the channel, the volume of sales increases. More Coca-Cola is sold by more retailers in more places. This is also economically advantageous to the manufacturer (Coca-Cola), since the retailer who buys the goods (in this case, many crates of Coke tins) must pay for the items and absorb some of the risks (the goods might be stolen from his store, or damaged on the way to the store or in the store).

- Channel specialists help channel members

Not everyone can do everything in a channel, so certain specialists can help the channel members. For example, a cold-storage company might specialize in warehousingOpens in new window and transportingOpens in new window frozen items like meats and dairy products. They help other channel members because of their specialization.

- Co-ordination and sorting function of channels

Channels sort and co-ordinate items for prospective customers. If you have ever been to a branch of Walmart or Spar, you know that you will find all the breakfast cereals in one area of the shop (for example, in aisle number 7). These shops co-ordinate and organize all items, and group them according to certain product categories.

- Assist the customer in the search process

Customers can now find the commodity produced, since it is available in a variety of locations (channels assist in the place utility). This allows the customers to shop, find the products and satisfy their needs. Channels assist the customer when searching for goods. I know, for example, that if I want a Bic pen I can go to any branch of the CAN in South Africa, and they will be available there.

- Intermediaries reduce many costs

Intermediaries can often reduce costs (as strange as this might sound). These include the following: selling costs (they have shops with buildings and staff); transportation costs; inventory carrying costs; order processing costs (they receive orders from customers); and customer service costs (they help customers with information about your product).

One intermediary, say a retail store like Walmart in the USA or Spar in Europe or Africa, can significantly increase the product’s market contact with the customer since many thousands of people travel through the store and buy the product.

- The CRAM Principle

- Contractual efficiency also assists channel members, since they are contractually bound to distribute goods effectively. Drawing up a contract means that channel members take their responsibility seriously (for example, the transportation company knows that it must deliver goods to the Walmart retail outlets on time).

- The routinization of transactions. Channels reduce costs by subjecting every transaction to routine. For example, one knows that one can go to a BP One-Stop service station and buy petrol at any time of the night or day.

- Retailers often offer a wide assortment of goods. For example, in the soap category they could stock Palmolive, Lux, Dove, and a wide assortment of other leading brands.

- Minimizing uncertainty is the next principle. It is always beneficial to minimize the uncertainty of the transaction for the customer. For example, customers know with certainty that they can always buy petrol at the BP One-Stop 24 hours a day. The newspaper salesman who stands on the same corner selling The Star at the same time every morning also provides the customer with certainty.

- J.C. Johnson, D.F. Wood, D.L. Wardlow, P.R. Murphy, Contemporary Logistics, seventh ed., Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 1999, pp. 1 – 21.

- A. Rushton, P. Crouche, P. Baker, The Handbook of Logistics and Distribution Management, third ed., Kogan Page, London, 2006.

- S.C. Ailawadi, R. Singh, Logistics Management, Prentice Hall of India, New Delhi, 2005.

- R.H. Ballou, Business Logistics/Supply Chain Management: Planning, Organizing, and Controlling the Supply Chain, fifth ed., Pearson-Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2004.

- J.R. Stock, D.M. Lambert, Strategic Logistics Management, fourth ed., Irwin McGraw-Hill, New York, 2001.

- G. Ghiani, G. Laporte, R. Musmanno, Introduction to Logistics Systems Planning and Control, John Wiley & Sons, NJ, 2004, pp. 6 – 20.

- M. Hugos, Essentials of Supply Chain Management, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken NJ, 2003, pp. 1 – 15.

- H.T. Lewis, J.W. Culliton, J.D. Steel, The Role of Air Freight in Physical Distribution, Division of Research, Graduate School of Business Administration, Harvard University, Boston, MA, 1956, p. 82.

- D. Riopel, A. Langevin, J.F. Campbell, The network of logistics decisions, in: A. Langevin, D. Riopel (Eds.), Logistics Systems: Design and Optimization, Springer, New York, 2005, pp. 12–17.

- M. Browne, J. Allen, Logistics of food transport, in: R. Heap, M. Kierstan, G. Ford (Eds.) Food Transportation, Blackie Academic & Professional, London, 1998, pp. 22–25.

- J. Drury, Towards More Efficient Order Picking, IMM Monograph No. 1, The Institute of Materials Management, Cranfield, 1988.