Theories of Relationship

Efficient Consumer Response

The efficient consumer response (ECR) is testament to an increased willingness for logistical cooperation. In downstream logistics, it is the company’s objective to satisfy the customer, rather than vice versa, by delivering the right product, at the right time, in the right quantity and at the right place.

ECR is defined as follows:

Efficient consumer response (ECR) is a strategy to increase the level of services to consumers through close cooperation among retailers, wholesalers and manufacturers by means of electronic data interchange (EDI).

Efficient consumer response (ECR) is a strategic concept compiled by a consulting firm Kurt Simon Associates at the request of organizations concerning the US processed food distribution industry, aiming to recover the competitive strength for surviving the turbulent time of the industry when discounters emerged in the USA.

By aiming to improve the efficiency of a supply chain as a whole beyond the wall of retailers, wholesalers and manufacturers, they can consequently gain larger profits than each of them pursuing their own business goals.

ECR echoes the idea whereby it is in the interests of the members of a channel to cooperate in order to improve its efficacy, evaluated on the basis of criteria such as the improvement of the service rate or the lowering of the number of breakdowns (PAC 97, p. 67).

While the implementation of this general model of partnership saves costs all along the chain, which runs from the food distributor to the industrial supplier (VAN 98). Companies who compose the supply cahin can reduce the opportunity loss, inventory level and entire costs, as well as increase monetary profitability by sharing the purpose of customer satisfaction.

Des Garets (DES 00) points out that the primary goal of ECR is the application of the following five basic principles:

- To provide the consumers with an added value in terms of products, quality, range, availability and rate of service, whilst reducing the cost of operating the supply chain;

- To adopt a logic of cooperation rather than one of transactional confrontation;

- To facilitate (the marketing, logistical and production choices) by way of rapid and reliable information exchange through the EDI (Electronic Data Interchange);

- To guarantee the availability of the right product at the right time;

- To distribute (by a measurement of overall efficacy) the benefits obtained by the partners” (p. 113).

Hence, ultimately, we find significant implicit convergences between the expectations of distribution logistics and overall logistics. Coordination by one and by the other underlies a process of interactions between those involved in the operations chain from downstream (the demand to be served) to upstream (supply), i.e. the manufacturing company, its suppliers and its logistics providers, but also its distributors who, by creating common distribution platforms and combined road networks, play an important role in the making of large-scale savings.

The IMP school first emerged in the late 1970s when a number of European researchers began investigating B2B relationships with the simple goal of describing them accurately. Some of the major contributors to the IMP school are:

- Malcolm Cunningham,

- David Ford,

- Lars-Erik Gadde,

- Hakan Hakansson,

- Ivan Snehota,

- Peter Naude and

- Peter Turnbull.

The IMP school argues that B2B transactions occur within the context of broader, long-term relationships, which are, in turn, situated within a broader network of relationships.

Any single B2B relationship between supplier and customer is composed of activity links, actor bonds and resources ties.

IMP researchers were among the first to challenge the view that transaction costs determined which supplier would be chosen by a customer. IMP researchers identified the importance of the impact of relationship history on supplier selection.

The characteristics of B2B relationships, from an IMP perspective, are as follows:

- Buyers and sellers are both active participants in transactions, pursuing solutions to their own problems rather than simply reacting to the other party’s influence.

- Relationships between buyers and sellers are frequently long term, are close in nature and involve a complex pattern of interaction between and within each company.

- Buyer-seller links often become institutionalized into a set of roles that each party expects the other to perform, and expectations that adaptations will be made on an ongoing basis.

- Interactions occur within the context of the relationship’s history and the broader set of relationships each firm has with other firms – the firm’s network of relationships.

- Firms choose which firms they interact with and how. The relationships that firms participate in can be many and diverse, carried out for different purposes, with different partners and have different levels of importance. These relationships are conducted within a context of a much broader network of relationships.

- Relationships are composed of actor bonds, activity links and resources ties, as now described.

Actor bonds are defined as follows:

Actor bonds are interpersonal contacts between actors in partner firms that result in trust, commitment and adaptation between actors.

Actor bonds are a product of interpersonal communication and the subsequent development of trustOpens in new window. Adaptation of relationships over time is heavily influenced by social bondingOpens in new window.

Activity links can be defined as follows:

Activity links are the commercial, technical, financial, administrative and other connections that are formed between companies in interaction.

Activities might centre on buying and selling, technical cooperation or inter-firm projects of many kinds. Activities such as inter-partner knowledge exchange, the creation of inter-partner IT systems, the creation of integrated manufacturing systems such as Just-In-Time (JIT)Opens in new window and Efficient Consumer Response (ECR)Opens in new window, the development of jointly implemented total quality management (TQM) processesOpens in new window, are investments that demonstrate commitment.

IMP researchers have focused on two major streams of activity-related research: the structure and cost-effectiveness of activity links, and the behavioral characteristics that enable relationships to survive. The reduction of transaction costs is an important consideration when customers form links with suppliers. Dyer argues that search costs, contracting costs, monitoring costs and enforcement costs (the four major types of transaction cost) can all be reduced through closer B2B relationships.

Resources are defined as follows:

Resources are the human, financial, legal, physical, managerial, intellectual and other strengths or weaknesses of an organization.

Resources ties are formed when these resources are deployed in the performance of the activities that link supplier and customer. Resources that are deployed in one B2B relationship may strengthen and deepen that relationship. However, there may be an opportunity cost. Once resources (for example, people or money) are committed to one relationship they might not be available to another relationship.

The Nordic School

The Nordic school emphasizes the role of service in supplier-customer relationships. The main proponents of the Nordic school are Christian Grönroos and Evert Gummersson.

The Nordic school emerged from research into services marketing that began in the late 1970s particularly in Scandinavia. The key idea advocated by the Nordic school is that service is a significant component of transactions between suppliers and their customers. Their work became influential in the development of the field of relationship marketing, which presents a challenge to the transactional view of marketing that has been dominant for so long. The Nordic school’s approach has application in both B2B and B2C environments.

Grönroos has defined relationship marketing as follows:

Relationship marketing is the process of identifying and establishing, maintaining, enhancing, and, when necessary, terminating relationships with customers and other stakeholders, at a profit, so that the objectives of all parties involved are met, where this is done by a mutual giving and fulfillment of promise.

Gummesson goes further, redefining marketing as follows:

Marketing can be defined as ‘interactions, relationships, and networks’.

The Nordic school identifies three major characteristics of commercial relationships — interaction, dialogue and value — known collectively as the ‘Triplet of Relationship Marketing’, and described further below.

- Interaction. Like the IMP school, the Nordic school suggests that inter-firm exchanges occur in a broader context of ongoing interactions. This is a significant departure from traditional notions of marketing where inter-firm exchanges are conceptualized as discrete, unrelated events, almost as if there is no history. From the Nordic school’s perspective, interactions are service-dominant. As customers and suppliers interact, each performs services for the other. Customers supply information; suppliers supply solutions.

- Dialogue. Suppliers and customers are in dialogue with each other. Indeed, communication between partners is essential to the functioning of the relationship. Traditional marketing thinking has imagined communication to be one-way, from company to customer, but the Nordic school emphasizes the fact that communication is bilateral.

- Value. The concepts of ‘value’, ‘value creation’ and ‘value creation systems’ have become more important to managers over the past 20 years. The Nordic school stresses the mutual nature of value. To generate value from customers, companies need to generate customer-perceived value; that is, create and deliver something that is perceived to be of value to customers. Value creation therefore requires contributions from both buyer and seller. From the Nordic school’s perspective, service performance is a key contributor to customer-perceived value.

The Nordic school is closely aligned with Service-Dominant Logic (SDL). SDL’s main proponents are Robert Lusch and Stephen Vargo. SDL claims that all firms, even manufacturing firms. We can all appreciate that a patient visiting a doctor receives a service – medical advice. How can this also be true of manufacturing? SDL argues that although a manufacturer may build printers, the manufacturer is providing a service to users when they use the printer to convert images on a computer screen into text on a page. The printer has no value until it is used. SDL takes a relational view of customer value. Neo-classical economists generally suggest that value is created (or at least measured) at the point of exchange; this is known as value-in-exchange. SDL, however, proposes that value is created when customers use the goods or services; this is known as value-in-use. It is customers who co-create value when they use or interact with products or services; firms do not create value in their factories and ship it to market. This conceptualization of value is inherently grounded in productive supplier-customer relationships wherein the supplier (and its supply chain) helps the customer to extract this value-in-use by marketing goods and services that helps the customer experience more and better value than the goods and services of competitors. The worldview of SDL involves reframing goods as services; they are merely the vessels through which service is delivered to customers, the embodiment of the know-how of the firm’s network of relationships (supply chain) in a format amenable to exchange. In such a worldview, every firm competes as part of a network, against other value networks, and relationships become critical.

The Anglo-Australian School

The Anglo-Australian school takes the view that companies not only form relationships with customers, but also with a wide range of other stakeholders including employees, shareholders, suppliers, buyers and governments. The main proponents of this school are Martin Christopher, Adrian Payne, Helen Pack and David Ballantyne.

Stakeholder relationships vary in intensity, according to the level of relationship investment, commitment and longevity. Unlike the IMP school that takes a descriptive approach, the Anglo-Australian school takes a more prescriptive approach. Its work sets out to help managers improve relationships with stakeholder groups.

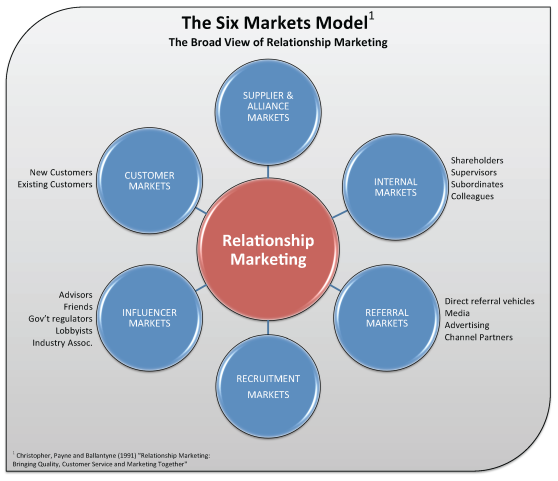

The major conceptual contribution of this school is their Six-Markets Model that has been revised several times (Figure X-1).

Figure X-1. The Six-Markets Model

Figure X-1. The Six-Markets ModelThe school’s researchers have focused on a number of topics: customer retention, customer loyalty, customer satisfaction, customer relationship economics and value creation. One of their major findings is that customer satisfaction and customer retention are drivers of shareholder value. |

The model suggest that firms must satisfy six major stakeholder ‘markets’; internal markets (employees), supplier/alliance markets (including major suppliers, joint venture partners and the like), recruitment markets (labor markets), referral markets (word-of-mouth advocates and cross-referral networks), influence markets (these include governments, regulators, shareholders and the business press) and customer markets (both intermediate and end-ursers).

The North American School

The North American school receives less emphasis as a separate school of relationship management than other schools. Significant contributors to this school are Jeffery Dyer, Sandy Jap, Shelby Hunt, Robert Dwyer, Jan Heide, Robert Morgan and Jagdish Sheth. A major theme flowing through this school’s work is the connection between successful inter-firm relationships and excellent business performance. The school acknowledges that relationships reduce transaction costs, and that trust and commitment are two very important attributes of successful relationships. Indeed, one of the more important theoretical contributions to come from the North American school is Morgan and Hunt’s ‘Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing’. This was the first time that trust was explicitly linked to commitment in the context of customer-supplier relationships. According to the theory, trust is underpinned by shared values, communication, non-opportunistic behavior, low functional conflict and cooperation. Commitment, on the other hand, is associated not only with high relationship termination costs, but also with high relationship benefits.

The North American school tends to view relationships as tools that a well-run company can manipulate for competitive advantage. They also focus on dyadic relationships rather than networks, most commonly buyer-supplier dyads or strategic alliance/joint venture partnerships.

The Asian (guanxi) School

Guanxi (pronounced Gwan-She) is, essentially, a philosophy for conducting business and other interpersonal relationships in the Chinese, and broader Asian, context. Therefore, its effects have a significant impact on how Asian societies and economies work.

Guanxi has been known to Western business people since at least 1978. This was the time when the Chinese market began to open up to the West. The foundations of guanxi are Buddhist and Confucian teachings regarding the conduct of interpersonal interactions.

Guanxi refers to the informal social bonds and reciprocal obligations between various actors that result from some common social context, for example families, friendships and clan memberships.

These are special types of relationship that impose reciprocal obligations to obtain resources through a continual cooperation and exchange of favors.

Guanxi has become a necessary aspect of Chinese and, indeed, Asian business due to the lack of codified, enforceable contracts such as those found in Western markets. Guanxi determines who can conduct business with whom and under what circumstances. Business is conducted within networks, and rules based on status are invoked. Network members can only extend invitations to others to become part of their network if the invite is a peer or a subordinate.

And to make it even more complex, one can imagine many customers dealing with many suppliers in a collaborative network of relationships. However, we will be begin by focusing upon the single dyad: a customer and a supplier.

Change within Relationships

Relationships change over time. Parties become closer or more distant; interactions become more or less frequent. Because they evolve, they can vary considerably, both in the number and variety of episodes, and the interactions that take place within those episodes.

Dwyer has identified five phases through which customer-supplier relationships can evolve.

- Awareness.

- Exploration.

- Expansion.

- Commitment.

- Dissolution.

- Awareness

Awareness is when each party comes to the attention of the other as a possible exchange partner.

- Exploration

Exploration is the period of investigation and testing during which the parties explore each other’s capabilities and performance. Some trial purchasing takes place. If the trial is unsuccessful the relationship can be terminated with few costs.

This exploration phase is thought to comprise five sub-processes: attraction; communication and bargaining; development and exercise of power; development of norms; and the development of expectations.

- Expansion

Expansion is the phase in which there is increasing interdependence. More transactions take place and trust begins to develop.

- Commitment

The commitment phase is characterized by increased adaptation on both sides and mutually understood roles and goals. Automated purchasing processes are a sure sign of commitment.

- Dissolution

Not all relationships will reach the commitment phase. Many are terminated before that stage. There may be a breach of trust that forces a partner to reconsider the relationship.

Relationship terminationOpens in new window can be bilateral or unilateral.

|

Customers exit relationships for many reasons, such as repeated service failures or changed product requirements.

Suppliers may choose to exit relationships because of the relationship’s failure to contribute to sales volume or profit goals. One option to resolve this problem and continue the relationship may be to reduce the supplier’s cost-to-serve the customer.

This discussion of relationship developmentOpens in new window highlights two attributes of highly developed relationships: trust and commitment. These have been the subjects of a considerable amount of research.

Core Elements of Relationship

Trust

Trust is focused. That is, although there may be a generalized sense of confidence and security, these feelings are directed. One party may trust the other party’s:

|

The development of trust is an investment in relationship-building which has a long-term payoff. Trust emerges as parties share experiences, and interpret and assess each other’s motives. As they learn more about each other, risk and doubt are reduced. For these reasons, trust has been described as the glue that holds a relationship together across time and different episodes.

When mutual trust exists between partners, both are motivated to make investments in the relationship. These investments, which serve as exit barriers, may be either tangible (e.g. property) or intangible (e.g. knowledge). Such investments may or may not be retrievable when the relationship dissolve.

If trust is absent, conflict and uncertainty rise, whilst cooperation falls. Lack of trust clearly provides a shaky foundation for a successful customer-supplier relationship.

Commitment

Commitment is an essential ingredient for successful, long-term relationships. Morgan and Hunt define relationship commitment as follows:

Commitment is shown by “an exchange partner believing that an ongoing relationship with another is so important as to warrant maximum effort to maintain it ; that is, the committed party believes the relationship is worth working on to ensure that it endures indefinitely”.

Commitment arises from trust, shared values and the belief that partners will be difficult to replace. Commitment motivates partners to cooperate in order to preserve relationship investments.

Commitment means partners forgo short-term alternatives in favor of more stable, long-term benefits associated with current partners. Where customers have choice, they make commitments only to trustworthy partners, because commitment entails vulnerability, leaving them open to opportunism.

For example, a corporate customer that commits future purchasing of raw materials to a particular supplier may experience the downside of opportunistic behavior if that supplier raises prices.

Evidence of commitment is found in the investments that one party makes in the other. One party makes investments in the promising relationship and if the other responds, the relationship evolves and the partners become increasingly committed to doing business with each other.

Investments can include time, money and the sidelining of current or alternative relationships. A partner’s commitment to a relationship is directly represented in the size of the investment in the relationship, since these represent termination costs.

Highly committed relationships have very high termination costs since some of these relationship investments may be irretrievable, for example, investments in capital equipment made for a joint venture. In addition there may be significant costs incurred in switching to an alternative supplier, such as search costs, learning costs and psychic (stress, worry) costs.

See Also:

- Singh, J. and Sirdeshmukh, D. (2000). Agency and trust mechanisms in consumer satisfaction and loyalty judgments. Journal of Marketing Science, 28(1), 255 – 71.

- Morgan, R.M. and Hunt, S.D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20 – 38.

- Wilson, D.T. and Mummalaneni, V. (1986). Bonding and commitment in supplier relationships: a preliminary conceptualization. Industrial Marketing and Purchasing, 1(3), 44 – 58.

- Ang, L. and Buttle, F.A. (2002). ROI on CRM: a customer journey approach. Proceedings of the Inaugural Asia-Pacific IMP conference, Bali, December.

- Ferron, J. (2000). The customer-centric organization in the automobile industry – focus for the 21st century. In S. Brown (ed.) Customer relationship management: a strategic imperative in the world of e-business. Toronto: John Wiley, pp. 189 – 211.