Consumer Behavior

Photo courtesy of Getty ImagesOpens in new window

Photo courtesy of Getty ImagesOpens in new window

Anyone might define consumer behavior as the study of how a person buys products. However, consumer behavior really involves quite a bit more, as this more complete definition elucidates: |

Consumer behavior reflects the totality of consumers’ decisions with respect to the acquisition, consumption, and disposition of goods, services, activities, experiences, people, and ideas by (human) decision-making units (over time).

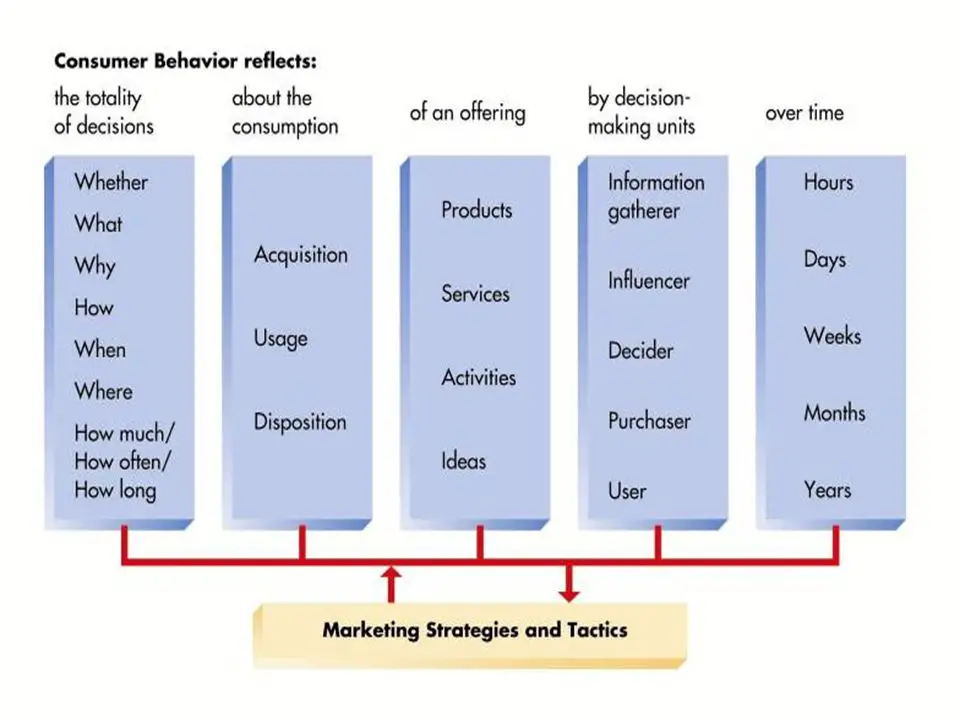

This definition has some very important elements, summarized in Figure X-1. The following sections present a closer look at each element.

Figure X-1. Source: The Internet

Figure X-1. Source: The Internet

|

Consumer Behavior Involves Goods, Services, Activities, Experiences, People, and Ideas

Consumer behavior means more than just the way that a person buys tangible products such as bath soap and automobiles. It also includes consumers’ use of services, activities, experiences, and ideas such as going to the dentist, attending a concert, taking a trip, and donating to UNICEF.

In addition, consumers make decisions about people, such as voting for politicians, reading books by certain authors, seeing movies or TV shows starring certain actors, and attending concerts featuring favorite bands.

Another example of consumer behavior involves choices about the consumption of time, a scarce resource. Will you check to see what’s happening on Facebook, search for a YouTube video, watch a sports event live, or record a program and watch it later, for instance?

How we use time reflects who we are, what our lifestyle are like, and how we are both the same and different from others. Because consumer behavior includes the consumption of so many things, we use the simple term offering to encompass these entities.

Offering is defined as a product, service, activity, experience, or idea offered by a marketing firm to consumers.

Consumer Behavior Involves More Than Buying

How consumers buy is extremely important to marketers. However, marketers are also intensely interested in consumer behavior related to using and disposing of an offering:

Acquiring

Buying represents one type of acquisition behavior.

Acquisition is the process by which a consumer comes to own an offering and includes other ways of obtaining goods and services, such as renting, leasing, trading, and sharing.

Acquisition also involves decisions about time as well as money. For example, when consumers experience a loss (i.e., make a purchase that does not work out well), they will perceive the time period until the next purchase as being shorter (because they want to remove negative feeling).

Consumers sometimes find themselves interrupted during a consumption experience; studies show interruption actually makes a pleasant experience seem more enjoyable when resumed.

Deadlines can also affect acquisition behavior: Consumers tend to procrastinate in redeeming coupons and gift cards with far-future deadlines, but move more quickly when deadlines are closer. Why? Because they do not want to regret having missed out and they expect to have more time to enjoy and indulge themselves with the acquisition in the future.

Using

After consumers acquire an offering, they use it, which is why usage is at the very core of consumer behavior.

Usage, by definition, is the process by which a consumer uses an offering.

Whether and why we use certain products can symbolize something about who we are, what we value, and what we believe.

The products we use on Christmas (e.g., making desserts from scratch or buying them in a bakery) may symbolize the event’s significance and how we feel about our guests. The music we enjoy (Lady Gaga or Paul McCartney) and the jewelry we wear (earring or engagement rings) can also symbolize who we are and how we feel.

Moreover, marketers must be sensitive to when consumers are likely to use a product, whether they find it effective, whether they control their consumption of it, and how they react after using it — do they spread positive or negative word-of-mouthOpens in new window reviews about a new film, for instance?

Disposing

Disposition, how consumers get rid of an offering they have previously acquired, can have important implications for marketers.

Consumers can give away their used possessions, sell them on eBay, or lend them to others. “Vintage” clothing stores now sell older clothes (disposed of by the original owners) that buyers find stylish.

Eco-minded consumers often seek out biodegradable products made from recycled materials or choose goods that do not pollute when disposed of. Municipalities are also interested in how to motivate earth-friendly disposition. Marketers see profit opportunities in addressing disposition concerns.

Terra-Cycle, for example, markets tote bags, pencil cases, and other products made from used packaging and recycled materials. In North and South America, Europe, and the Baltic, it partners with firms such as PepsiCo to collect mountains of discarded packaging and turn them into usable products for sale.

Consumer Behavior Is a Dynamic Process

The sequence of acquisition, consumption, and disposition can occur over time in a dynamic order—hours, days, weeks, months, or years, as shown in Figure X-1.

Disposition consists when consumers dispose of old products they acquired in a number of ways, oftentimes through recycling or vintage shops.

To illustrate, assume that a family has acquired and is using a new car. Usage provides the family with information—whether the car drives well and is reliable—that affects when, whether, how, and why members will dispose of the car by selling, trading, or junking it. Because the family always needs transportation, disposition is likely to affect when, whether, how, and why its members acquire another car in the future.

Entire markets are designed around linking one consumer’s disposition decision to other consumer’s acquisition decisions. When consumers buy used cars, they are buying cars that others have disposed of. From eBay’s online auctions to Goodwill Industries’ secondhand clothing stores, from consignment shops to used books sold online, many businesses exist to link one consumer’s disposition behavior with another’s acquisition behavior.

Broad changes in consumer behavior occur over time, as well. Fifty years ago, consumers had far fewer brand choices and were exposed to fewer marketing messages. In contrast, today’s consumers are more connected, easily able to research offerings online, access communications and promotions in multiple media, and check what others think of brands with a quick search or social media post.

Consumers can also collaborate with marketers or with each other to create new products. For example, thousands of consumers participate when Mountain Dew requests ideas for new soft-drink flavors, product logos, and new ads. Then, consumers become cocreators of products.

Consumer Behavior Can Involve Many People

Consumer behaviors does not necessarily reflect the action of a single individual.

A group of friends, a few coworkers, or an entire family may plan a birthday party or decide where to have lunch, exchanging ideas in person, on the phone, via social media, or by e-mail or text message.

Moreover, the individuals engaging in consumer behavior can take on one or more roles. In the case of a car purchase, for example, one or more family members might take on the role of information gatherer by researching different models.

Others might assume the role of influencer and try to affect the outcome of a decision. One or more members may take on the role of purchaser by actually paying for the car, and some or all may be users. Finally, several family members may be involved in the disposal of the car.

Consumer Behavior Involves Many Decisions

Consumers behavior involves understanding whether, why, when, where, how, how much, how often, and for how long consumers will buy, or dispose of an offering (refer back to Figure X-1).

Whether to Acquire/Use/Dispose of an Offering

Consumers must decide whether to acquire, use, or dispose of an offering. They may need to decide whether to spend or save their money when they earn extra cash.

How much they decide to spend may be influenced by their perception of how much they recall spending in the past. They may need to decide whether to order a pizza, clean out a closet, or download a movie. Some consumers collect items, for example, a situation that has created a huge market for buying, selling, transporting, storing, and insuring collectible items.

Decisions about whether to acquire, use, or dispose of an offering are often related to personal goals, safety concerns, or a desire to reduce economic, social, or psychological risk.

What Offering to Acquire/Use/Dispose of

Consumers make decisions every day about what to buy; in fact, each U.S. household spends an average of $138 per day on goods and services.

In some cases, we make choices among product or service categories such as buying food versus downloading new music. In other cases, we choose between brands such as whether to buy a Kindle or a NOOK e-book reader. Our choices multiply daily as marketers introduce new products, sizes, and packages.

Why Acquire/Use/Dispose of an Offering

Consumption can occur for a number of reasons. Among the most important reasons, as you see later, are the ways in which an offering meets someone’s needs, values, or goals.

Some consumers acquire tattoos as a form of self-expression, to fit into a group, or to express their feelings about someone or something. In New York City, the Social Tattoo Project provides free tattoos of Twitter hashtags to highlight social causes (#poverty for example). Taking the self-expression of tattoos into the automotive arena, Ford has offered dozens of vinyl wrap “tattoos” for buyers to use in personalizing their Ford Focus cars.

Sometimes our reason for using an offering are filled with conflict, which leads to some difficult consumption decisions. Teenagers may smoke, even though they know it is harmful, because they think smoking will help them gain acceptance. Some consumers may be unable to stop acquiring, using, or disposing of products. They may be physically addicted to products such as cigarettes, or they may have a compulsion to eat, gamble, or buy.

Why an Offering Is Not Acquired/Used/Disposed Of

Marketers also try to understand why consumers do not acquire, use, or dispose of an offering. For example, consumers may delay buying a tablet computer because they believe that the product will soon be outdated or that some firms will leave this market, leaving them without after-sale support or service.

At times, consumers who want to acquire or consume an offering are unable to do so because what they want is unavailable. Ethics and social responsibility can also play a role. Some consumers may want to avoid products made in factories with questionable labor practices or avoid movies downloaded, copied, and shared without permission.

How to Acquire/Use/Dispose of an Offering

Marketers gain a lot of insight by understanding how consumers acquire, consume, and dispose of an offering.

Ways of Acquiring and Offering

How do consumers decide whether to acquire an offering in a store or mall, online, or at an auction? How do they decide whether to pay with cash, a check, a debit card, a credit card, an electronic system such as PayPal, or a “mobile wallet” payment app on their smartphones?

These examples relate to consumers’ buying decisions, but Table 1 shows that consumers can acquire an offering in other ways. Sharing is a form of acquisition, such as sharing possessions within a family or sharing videos via YouTube.

| Table 1 › › Eight Ways to Acquire an Offering | |

|---|---|

| Acquisition method | Description |

| Buying | Buying is a common acquisition method used for many offerings. |

| Trading | Consumers might receive a good or service as part of a trade. |

| Renting or leasing | Instead of buying consumers rent or lease cars, furniture, holiday homes and more. |

| Bartering | Consumers (and businesses) can exchange goods or services without having money change hands. |

| Gifting | Each society has many gift-giving occasions as well as informal or formal rules dictating how gifts are to be given, what is an appropriate gift and how to respond to a gift. |

| Finding | Consumers sometimes find goods that others have lost (hats left on a train) or thrown away. |

| Stealing | Because various offerings can be acquired through theft, marketers have developed products to deter this acquisition method, such as alarms to deter car theft. |

| Sharing | Another method of acquisition is by sharing or borrowing. Some types of sharing are illegal and border on theft, as when consumer copy and share movies. |

Ways of Using an Offering

In addition to understanding how consumers acquire an offering, marketers want to know how consumers use an offering. For obvious reasons, marketers want to ensure that their offering is used correctly. Improper usage of offerings like cough medicine or alcohol can create health and safety problems.

Because consumers may ignore label warnings and directions on potentially dangerous products, marketers who want to make warnings more effective have to understand how consumers process label information.

Ways of Disposing of an Offering

Sometimes nothing but the packaging remains of an offering (such as food) after it has been consumed. This leaves only a decision about whether to recycle or not and how. Consumers who want to dispose of a tangible product have several options:

- Find a new use for it: Using an old toothbrush to clean rust from tools or making shorts out of an old pair of jean shows how consumers can continue using an item instead of disposing of it.

- Get rid of temporarily. Renting or lending an item is one way of getting rid of it temporarily.

- Get rid of it permanently: Throwing away an item, sending it to a recycling centre, trading it, giving it away or selling it are all ways to get rid of it permanently. However, some consumers refuse to throw away things that they regard as special, even if the items no longer serve a functional purpose.

When to Acquire/Use/Dispose of an Offering

The timing of consumer behavior can depend on many factors, including our perceptions of and attitudes toward time itself. Consumers may think in terms of whether it is “time for me” or “time for others” and whether acquiring or using an offering is planned or spontaneous.

In cold weather, our tendency to rent movies, call for a tow truck, or shop for clothes is greatly enhanced. At the same time, we are less likely to eat ice cream, shop for a car, or look for a new home during cold weather. Time of day influences many consumption decisions, which is why Panera Bread is starting to add drive-throughs to accommodate breakfast customers in a hurry.

Our need for a variety can affect when we acquire, use, or dispose of an offering. We may decide not to eat a sandwich for lunch today if we have already had it every other day this week.

Transitions such as graduation, birth, retirement, and death also affect when we acquire, use, and dispose of offerings. For instance, we buy wedding rings when we get married. When we consume can be affected by traditions influenced by our families, our culture, and the area in which we live.

Decisions about when to acquire or use an offering are also affected by knowing when others might or might not be buying or using it. Thus, we might choose to go to the gym when we know that others will not be doing so.

In addition, we may wait to buy until we know something will be on sale; even if we have to line up to buy something popular, we are likely to continue waiting if we see many people joining the line behind us. Also, waiting to consume a pleasurable product such as candy increases our enjoyment of its consumption, even though we may be frustrated by having to wait.

Another decision is when to acquire a new, improved version of a product we already own. This can be a difficult decision when the current model still works well or has sentimental value. However, marketers may be able to affect whether and when consumers buy upgrades by providing economic incentives for replacing older products.

Where to Acquire/Use/Dispose of an Offering

Transitions such as graduation, birth, retirement, and death also affect when we acquire, use, and dispose of offerings. Consumers have more choices of where to acquire, use, and dispose of an offering than they have ever had before, including making purchases in stores, by mail, by phone, and over the Internet.

The Internet has changed where we acquire, use, and dispose of goods. Many consumers buy online via computer or smartphone because they like the convenience or the price or to acquire unique products. And as the success of craigslist shows, the Internet can help people dispose of goods that are then acquired by others.

In addition to acquisition decisions, consumers also make decisions about where to consume various products. For example, the need for privacy motivates consumers to stay home when using products that determine whether they are ovulating or pregnant.

On the other hand, wireless connections allow consumers in public places to make phone calls, post messages to social media sites, play computer games, and download photos or music from anywhere in the world. Consumers can also make charitable donations via text messages.

Finally, consumers make decisions regarding where to dispose of goods.

- Should they toss an old magazine in the trash or the recycling bin?

- Should they store an old photo album in the attic or give it to a relative?

Older consumers, in particular, may worry about what will happen to their special possessions after their death and about how to divide heirlooms without creating family conflict. These consumers hope that members will serve as a legacy for their heirs. A growing number of consumers are recycling unwanted goods through recycling agencies or nonprofit groups or giving them directly to other consumers through websites like The Freecycle Network.

How Much, How Often, and How Long to Acquire/Use/Dispose of an Offering

Consumers must take decisions about how much of a good or service they need; how often they need it; and how much time they will spend in acquisition, usage, and disposition. Usage decisions can vary widely from person to person and from culture to culture. For example, consumers in Switzerland eat twice as much chocolate as consumers in Russia.

Sales of a product can be increased when the consumer:

- uses larger amounts of the product,

- uses the product more frequently, or

- uses it for longer periods of time.

Bonus packages may motivate consumers to buy more of a product, but does this stockpiling lead to higher consumption? In the case of food products, consumers are more likely to increase when consumers sign up for flat-fee pricing covering unlimited consumption of telephone services or other offerings. However, because many consumers who choose flat-fee programs overestimate their likely consumption, they often pay more than if they had chosen per-usage pricing.

Some consumers experience problems because they engage in more acquisition, usage, or disposition than they should. For example, they may have a compulsionOpens in new window to overbuy, overeat, smoke, or gamble too much. Researchers are also investigating what affects consumers’ abilities to control consumption temptations and what happens when self-control falters, an issue for anybody who has tried to diet or make other changes to consumption habits.

Consumer Behavior Involves Emotions and Coping

Consumer researchers have studied the powerful role that emotionsOpens in new window play in consumer behavior. PositiveOpens in new window and negative emotionsOpens in new window as well as specific emotions like hopeOpens in new window, fearOpens in new window, regret, guiltOpens in new window, embarrassmentOpens in new window, and general moods can affect how consumers think, the choices they make, how they feel after making a decision, what they remember, and how much they enjoy an experience.

Emotions like loveOpens in new window sometimes describe how we feel about certain brands or possessions. Consumers often use products to regulate their feelings—as when a scoop of ice cream seems like a good antidote to a bad quiz score. Researchers have also studied how service employees’ emotions can affect consumers’ emotions outside of their awareness. And low-level emotions can be very important in low-effort situations (e.g, the low-level feelings we get from viewing a humorous ad).

Because issues related to consumer behavior can involve stress, consumers often need to cope in some way. Researchers have studied how consumers cope with difficult choices and an overwhelming array of goods from which to choose, how consumers use goods and services to cope with stressful events like having cancer; and how they cope with losing possessions due to divorce, natural disasters, moving to residential-care facility, and other incidents. They have even studied the coping behavior of certain market segments, such as low-literacy consumers, who often find it challenging to understands the marketplace without being able to read.