Negative Emotions

Graphics courtesy of Little LeagueOpens in new window

Graphics courtesy of Little LeagueOpens in new window

Although experiencing negative emotions may be unpleasant, the immediate negative reactions that we have to situations are often functional. For example, when we experience fearOpens in new window at the sound of a rattle at our feet, we jump back to avoid the rattle-snake. When we bring food to our mouths and smell a foul odor, we feel disgustOpens in new window, put down the fork, and push the plate away. According to the leading theories about emotion, the function of negative emotions is to enhance our survival. |

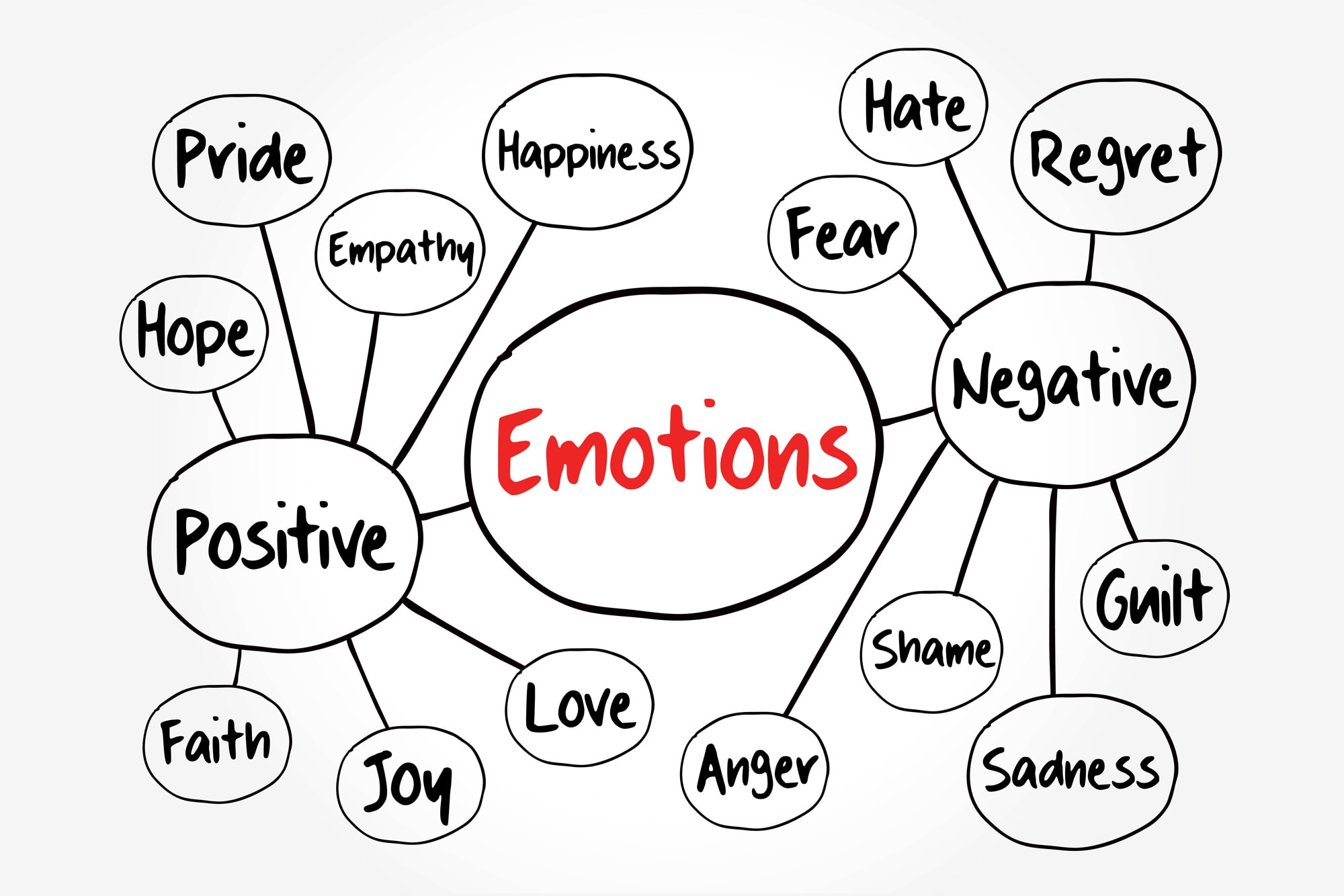

The negative emotions and affective states are many and diverse. Examples include fearOpens in new window, angerOpens in new window, disgustOpens in new window, sadnessOpens in new window, jealousyOpens in new window, envyOpens in new window, shameOpens in new window, guiltOpens in new window, contemptOpens in new window, anxietyOpens in new window, hate, depressionOpens in new window, and hopelessnessOpens in new window, to name a few.

When perusing this list, it may have occurred to the reader that it is difficult to think of some of these emotional states as functional. For instance, what is the use of feeling hopelessness, or even sadness? Is hate functional? Frijda (1994) addressed this issue in his chapter “Emotions Are Functional, Most of the Time.”

Frijda compares the functionality of emotions to the functionality of language. The function of language is to communicate, but we often produce sentences that do little to communicate whatever we intended to communicate, and we sometimes even produce sentences that get us in trouble. According to Frijda, it is the same with emotions.

In general, emotions serve a function. However, therea are many cases in which our experience, expression, or reactions to our emotions can serve us ill rather than serve us well. In fact, in the history of the study of emotion, researchers have focused more on the ways in which negative emotions are dysfunctional than on the ways in which negative emotions are functional.

However, some scholars have devoted their work lives to a more general understanding of negative emotions, and basic knowledge has progressed rapidly. Many emotion theories view negative emotions as ech being associated with a specific action tendency (e.g, Frijda, 1986; Tooby & Cosmides, 1990).

For example, angerOpens in new window is linked with an urge to attack and fear with an urge to escape. The action tendency does not mean that the organism must engage in the particular behavior in any particular way, but a general urge exists. Some cognitive (thinking) aspects are associated with these action tendencies.

According to research findings, negative emotions are linked with a focusing (narrowing) of attention, in contrast with positive emotionsOpens in new window, which are associated with an expanding of attention.

This focusing is functional; the individual can attend specifically to the threat or other relevant stimulus and block out other stimuli, thus being maximally prepared to take the action necessary for survival.

Frederickson (2001) has developed a theory of positive emotion that has proven helpful for understanding positive emotions and that additionally serves to shed light on the function of negative emotions.

Her broaden-and-build theoryOpens in new window proposes that positive emotions function to broaden our perceptions and cognitions, leading to an openness and flexibility in thinking.

The benefit of positive emotionsOpens in new window comes in the long run (the build part of her theory) because while broadening, the individual also builds physical, intellectural, and social resources that can help him in the future. For instance, while feeling joy and playing (say, a game of softball), the individual may build muscular strength and coordination.

Additionally, he may exhibit glee and have a good laugh with others, building social relationships. By contrast, negative emotions are most helpful in the short term; in general, negative emotions have little in the way of building effects. Those negative emotions that are functional arise as a reaction to an immediate stimulus, are linked with a tendency to produce a fairly specific action, and typically dissipate at the conclusion of the event.

See also:

- Fredrickson, B.L., & Cohn, M.A. (2008). Positive emotions. In M. Lewis, J.M. Haviland-Jones, & L.F. Barrett (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (3rd ed., pp. 777 – 796). New York: Guilford.

- Basso, M.R., Schefft, B.K., Ris, M.D., & Dember, W.N. (1996). Mood and global-local visual processing. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 2, 249 – 255.

- Fredrickson, B.L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56, 218 – 226.

- Frijda, N.H. (1986). The emotions. Cambridge, England: Cambridge Univeristy Press.

- Frijda, N.H. (1994). Emotions are functional, most of the time. In P. Ekman & R. Davidson (Eds.), The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions (pp. 112 – 122). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (1990). The past explains the present: Emotional adaptations and the structure of ancestral environments. Ethology and Sociobiology, 11, 375 – 424.