Borderline Personality Disorder

Clinical Presentation

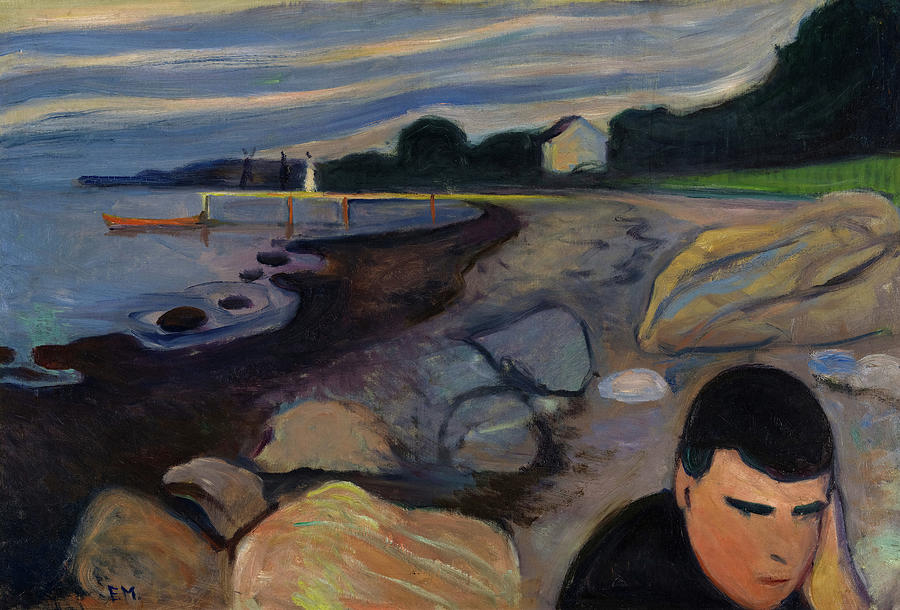

Art Work by Fine Art America® Opens in new window

Art Work by Fine Art America® Opens in new window

Individuals with borderline personalities present with a complex clinical picture, including diverse combinations of angerOpens in new window, anxietyOpens in new window, intense and labile affect, and brief disturbances of consciousness such as depersonalizationOpens in new window and dissociationOpens in new window. |

In addition, their symptomatic presentation includes lonelinessOpens in new window, a sense of emptiness, boredomOpens in new window, volatile interpersonal relations, identity confusion, and impulsive behavior that can include self-injury or self-mutilation. Stress can even precipitate a transient psychosis. Some conceptualize this disorder as a level of personality organization rather than as a specific personality disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

The borderline personality is characterized by the following behavior and interpersonal styles, cognitive style, and emotional style.

Behaviorally, borderlines are characterized by physically self-damaging acts such as suicide gestures, self-mutilation, or the provocation of fights.

Their social and occupational accomplishments are often less than their intelligence and ability warrant. Of all the personality disorders, they are more likely to have irregularities of circadian rhythms, especially of the sleep-wake cycle. Thus, chronic insominia is a common complaint.

Interpersonally, borderlines are characterized by their paradoxical instability. That is, they fluctuate quickly between idealizing and clinging to another individual, to devaluing and opposing that individual. They are exquisitely rejection-sensitive, and experience abandonment depression following the slightest of stressors.

Millon (2011) considered separation anxietyOpens in new window as a primary motivator of this personality disorder. Interpersonal relationships develop rather quickly and intensely, yet borderlines’ social adaptivenesss is rather superficial.

They are extraordinarily intolerant of being alone, and they go to great lengths to seek out the company of others, whether in indiscrimininate sexual affairs, late-night phone calls to relatives and recent acquaintances, or after-hours visits to hospital emergency rooms, with a host of vague medical and/or psychiatric complaints.

Their cognitive style is described as inflexible and impulsive (Millon, 2011).

Inflexibility of their style is characterized by rigid abstractions that easily lead to grandiose, idealized perceptions of others, not as real people, but as personifications of “all good” or “all bad” individuals.

They reason by analogy from past experiences and thus have difficulty reasoning logically and learning from past mistakes. Because they have an external locus of control, borderlines usually blame others when things go wrong.

By accepting responsibility for their own incompetence, borderlines believe they would feel even more powerless to change circumstances. Accordingly, their emotionsOpens in new window fluctuate between hopeOpens in new window and despairOpens in new window, because they believe that external circumstances are well beyond their control (Shulman, 1982).

Their cognitive style is also marked by impulsivity, and just as they vacillate between idealizationOpens in new window and devaluation of others, their thoughts shift from one extreme to another:

“I like people; no, I don’t like them”; “Having goals is good; no, it’s not”; “I need to get my life together; no, I can’t, it’s hopeless.”

This inflexibility and impulsivityOpens in new window complicate the process of identity formation. Their uncertainty about self-image, gender identity, goals, values, and career choice reflects this impulsive and flexible stance.

Gerald Adler (1985) suggested that borderlines have an underdeveloped evocative memory. As a result, they have difficulty recalling images and feeling states that could structure and soothe them in times of turmoil. Their inflexibility and impulsivity are further noted in their tendency toward splitting.

Splitting is the inability to synthesize contradictory qualities, such that the individual views others as all good or all bad, and utilizes “projective identification,” that is, attributing his or her own negative or dangerous feelings to others.

Their cognitive style is further exacerbated by an inability to tolerate frustration.

Finally, micropsychotic episodes can be noted when these individuals are under a great deal of stress. These are ill-defined, strange thought processes, especially noted in response to unstructured rather than structured situations, and may take the form of derealizationOpens in new window, depersonalizationOpens in new window, intense rage reactions, unusual reactions to drugs, and intense brief paranoid episodes.

Because of difficulty in focusing attention, and subsequent loss of relevant data, borderlines also have a diminished capacity to process information.

The emotional style of individuals with this disorder is characterized by marked mood shifts from a normal or euthymic mood to a dysphoric mood.

In addition, inappropriate and intense anger and rage may easily be triggered. On the other extreme are feelings of emptiness, a deep “void,” or boredomOpens in new window.

DSM-5 Characterization

Individuals with this personality disorder are characterized by an unremitting pattern of unstable relationships, emotional reactions, identity, and impulsivity.

They engage in frantic efforts to avoid abandonment, whether it is real or imagined. Their interpersonal relationships are intense, unstable, and alternate between the extremes of idealization and devaluation.

They have chronic identity issues and an unstable sense of self. Their impulsivity can result in self-damaging actions such as reckless driving or drug use, binge-eating, or high-risk sex.

These individuals engage in recurrent suicidal threats, gestures, acting out, or self-mutilating behavior. They can exhibit markedly reactive moods, chronic feelings of emptiness, emotional outbursts, and difficulty controlling their anger. They may also experience brief stress-related, paranoid thinking, or severe episodes of dissociation (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

| Case Example: Mr. B. |

|---|

| Mr. B. is a 29-year-old unemployed male who was referred to the hospital emergency room by his therapist at a community mental health center after two days of sustained suicidal gestures. He appeared to function adequately until his senior year in high school, when he became preoccupied with transcendental mediation. He had considerable difficulty concentrating during his first semester of college and seemed to focus most of his energies on finding a spiritual guru. At times, massive anxiety and feelings of emptiness swept over him, which he found would suddenly vanish if he lightly cut his wrist enough to draw blood. He had been in treatment with his current therapist for 18 months and become increasingly hostile and demanding as a patient, whereas earlier he had been quite captivated with his therapist’s empathy and intuitive sense. Lately, his life seemed to center on these twice-weekly therapy sessions. Mr. B.’s most recent suicidal gesture followed the therapist’s disclosure that he was relocating to a new job in another state. |

Biopsychosocial – Adlerian Conceptualization

The following biopsychosocial formulation may be helpful in understanding how the borderline personality pattern is likely to have developed. Biologically, borderlines can be understood in terms of the three main subtypes:

- borderline-dependent,

- borderline-histrionic, and

- borderline-passive-aggressiveOpens in new window.

The temperamental style of the borderline-dependent type is that of the passive-infantile pattern (Millon, 2011).

Millon hypothesized that low autonomic-nervous-system reactivity plus an overprotective parenting style facilitates restrictive interpersonal skills and a clinging relational style. On the other hand, the histrionic subtype was more likely to have a hyper-responsive infantile pattern. Thus, because of high autonomic-nervous-system reactivity and increased parental stimulation and expectations for performance, the borderline-histrionic pattern was likely to result.

Finally, the temperamental style of the passive-aggressive borderline was likely to have been the “difficult child” type noted by Thomas and Chess (1977). This pattern, plus parental inconsistency, marks the affective irritability of the borderline-passive-aggressive personality.

Psychologically, borderlines tend to view themselves, others, the world, and life’s purpose in terms of the following themes. They view themselves by some variant of the theme:

“I don’t know who I am or where I’m going.”

In short, their identity problems involve gender, career, loyalties, and values, while their self-esteem fluctuates with each thought or feeling about their self-identity.

Borderlines tend to view their world with some variant of the theme:

“People are great; no, they are not”; “Having goals is good; no, it’s not”; or, “If life doesn’t go my way, I can’t tolerate it.”

As such, they are likely to conclude:

“Therefore keep all options open. Don’t commit to anything. Reverse roles and vacillate thinking and feelings when under attack.”

The most common defense mechanismsOpens in new window utilized by Borderline Personality Disordered individuals are regression, splitting, and projective identification.

Socially, predictable patterns of parenting and environmental factors can be noted for the Borderline Personality Disorder. Parenting style differs depending on the subtype. For example, in the dependent subtype, overprotectiveness characterizes parenting, whereas in the histrionic subtype, a demanding parenting style is more evident, while an inconsistent parenting style is more noted in the passive-aggressive subtype.

But because the borderline personality is a syndromal elaboration and deterioration of the less severe Dependent, Histrionic, or Passive-Aggressive Personality Disorders (Millon, 2011), the family of origin in the borderline subtypes of these disorders is likely to be much more dysfunctional, increasing the likelihood that the child will have learned various self-defeating coping strategies. The parental injunction is likely to have been, “If you grow up and leave me, bad things will happen to me (parent).”

This borderline pattern is confirmed, reinforced, and perpetuated by the following individual and systems factors: Diffuse identity, impulsive vacillation, and self-defeating coping strategies lead to aggressive acting out, which leads to more chaos, which leads to the experience of depersonalization, increased dysphoria, and/or self-mutilation to achieve some relief. This leads to further reconfirmation of their beliefs about self and the world, as well as reinforcement of the behavioral and interpersonal patterns.

Treatment Considerations

The Borderline Personality Disorder is becoming one of the most common Axis II presentations seen in both public sector and in private practice. It can be among the most difficult and frustrating conditions to treat. Clinical experience suggests that it is important to assess the individual for overall level of functioning and for subtype.

The higher-functioning borderline-dependent personality has a higher probability for collaborating in psychotherapeutic treatment than the lower-functioning borderline-passive-aggressive personality.

Higher-functioning borderlines possibly may be engaged in insight-oriented psychotherapy without undue regression and acting out. Masterson (1976) suggested that rather than using traditional interpretation methods with borderlines, the therapist should utilize confrontational statements in which borderlines are asked to look at their behavior and its consequences.

With lower-functioning patients, treatment goals may be much more limited. Here, the focus of treatment would be on increasing day-to-day stable functioning. Treatment strategies and methods are varied for the treatment of borderline subtypes.

Strategies range from long-term psychotherapy, lasting two or more years, to rather short-term formats in which sessions are scheduled biweekly or even monthly, except when crises arise. Task-oriented group therapy has been shown to be a useful adjunct, as well as a primary treatment in and of itself (Linehan, 1987).

The rationale for group therapy with the borderline is that the intense interpersonal relationship that forms between the therapist and the patient, and serves as the trigger for so much acting out, is effectively reduced in a group format. Whether seen individually or in a group format, the therapist does well to clearly articulate treatment limits and objectives.

For the lower-functioning borderlines and the histrionic and passive-aggressive subtypes, a particularly useful procedure is to employ a written treatment contract. Antidepressants are often used with borderline patients and are particularly aimed at target symptoms such as insomnia, depression, or anxiety disorders. Low-dose neuroleptics are often utilized as well.

AntidepressantOpens in new window, mood-stabilizing, antianxiety, and antipsychotic drugs are also sometimes used to treat people with BDP, although medication treatment is controversial given the high rate of suicide attempts among those suffering from BPD. Over the past two to three decades, treatments for BPD have improved, and many sufferers can live productive lives.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author.

- James, L.M., & Taylor, J. (2008). Associations between symptoms of borderline personality disorder, externalizing disorders, and suicide-related behaviors. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 30, 1 – 9.

- Lieb, K., Zanarinin, M.C., Schmahl, C., Linehan, M.M., & Bohus, M. (2004). Borderline personality disorder. Lancet, 364, 453 – 461.

- Linehan, M.M., Cochran, B.N., & Kehrer, C.A. (2001). Dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder. In D. H. Barlow (Ed.), Clinical handbook of psychological disorders (3rd ed., pp. 470 – 522). New York: Guilford.

- Norra, C., Mrazek, M., Tuchtenhagen, F., Gobbele, R., Buchner, H., SaB, H., et al. (2003). Enhanced intensity dependence as a marker of low serotenergic neurotransmission in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 37, 23 – 33.

- Sansone, R.A., Songer, D.A., & Miller, K. A. (2005). Childhood abuse, mental healthcare utilization, self-harm behavior, and multiple psychiatric diagnosis among inpatients with and without a borderline diagnosis. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 46, 117 – 120.

- Soloff, P. H., Fabio, A., Kelly, T.M., Malone, K. M., & Mann, J. J. (2005). High-lethality status in patients with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 19, 386 – 399.