Limbic System

The limbic system is a group of brain areas including the hypothalamus, anterior thalamus, cingulated gyrus, hippocampus, amygdale, septal nuclei, orbitofrontal cortex, and portions of the basal ganglia. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, American physician and neuroscientist Paul MacLean (1949, 1952) proposed that these structures constitute the emotional brain.

The relationship between emotion and several of the limbic system structures (specifically, the hypothalamus, anterior thalamus, cingulated gyrus, and hippocampus) was first proposed by American neuroanatomist Dr. James Papez in his theoretical paper in 1937. These four brain structures were called the Papez circuit because they form a circuitous chain.

In developing his theory, Papez built on information from at least three sources. First, research by Cannon (1915/1929) and Bard (1929), in which they systematically damaged or removed parts of the brain in animals, demonstrated that the hypothalamus is necessary for an animal to produce an integrated emotional expression (e.g., a cat’s behavior when threatened of crouching down, hissing, with ears back, claws ready). Without the hypothalamus, the animal may produce some but not all behaviours characteristic of a particular emotional expression.

Second, anatomist C. Judson Herrick (1933) had proposed a theory that distinguished between two parts of the cortex: the lateral (newer, from an evolutionary point of view) and medial (older).

According to Herrick, the lateral cortex was responsible for sensation, motor function, and higher-order thinking in humans, while the medial cortex was involved with more primitive functions. Third, Papez had learned about research on damage to the the medial cortex resulting in emotional dysfunction.

Credit: UT HealthOpens in new window

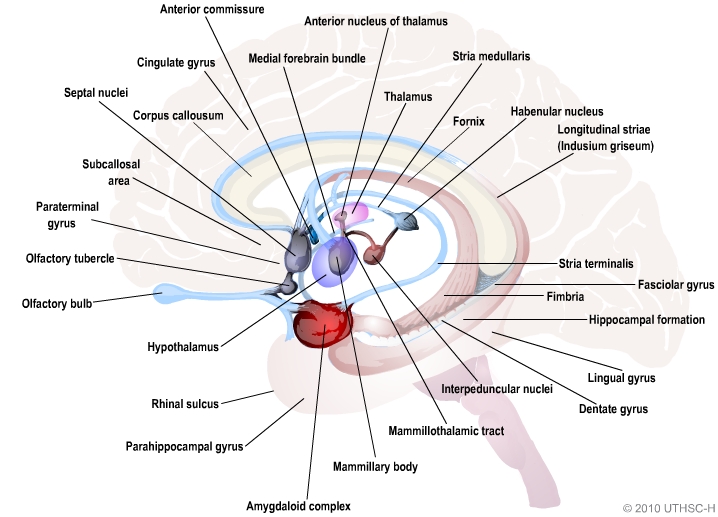

Credit: UT HealthOpens in new windowThe limbic system of the human brain. The limbic system is the set of brain structures that forms the inner border of the cortex and is believed to support a variety of functions including emotion, behavior, long-term memory, and olfaction. (ABC-CLIO) |

Papez theorized that the neural circuit for behavioral expression of emotion was primarily governed by the hypothalamus, while the actual experience (subjective feeling) of emotion was produced through the interactions among different structures in the Papez circuit.

These other structures were part of the medial cortex, which presumably was a part of the cortex common across mammal species and which was relatively “primitive,” as Herrick had said. These structures would not have language processing as a focus and were candidates for emotional experience, which can occur viscerally, without verbal labels or higher-order thinking.

Over 10 years later, MacLean integrated Papez’s theory and other work, proposing the limbic system, the “emotional brain”. As previously described, the limbic system includes the brain structures of the Papez circuit plus additional structures. MacLean discussed the importance of the hypothalamus in behavioral expression of emotion and the cerebral cortex in the experience of emotion.

Starting with the hypothalamus as the center, and as a part of the brain with demonstrated involvement in emotion, he reasoned that other parts of the brain that are involved with emotion must be connected (by nerve fibers) to the hypothalamus. Most of the newer (more recently evolved) cortex did not have strong connections to the hypothalamus, but many parts of the medial cortex did.

Based on both the observation of neural connections to the hypothalamus and clinical evidence, MacLean thus added brain structures to Papez’s circuit. Other than the hypothalamus, MacLean suggested the hippocampus was the primry brain structure involved in emotional experience, because of both its location and its anatomy (LeDoux, 1996).

The nerve cells (neurons) of the hippocampus are large and located next to one another in an orderly fashion. MacLean referred to the hippocampal neurons as an “emotional keyboard,” the firing of particular neurons being associated with particular emotions. As hippocampal neurons lack the analyzing capacity of other neurons associated with more advanced anatomy, experience associated with stimulation of hippocampal neurons is relatively crude.

MacLean’s theory was extremely influential and has played a large role in the development of knowledge about human emotion. However, the limbic system theory—at least as MacLean presented it—is largely unsupported. LeDoux (1996) describes a number of shortcomings with this theory.

- First, research indicates that the hippocampus plays a more significant role in memory than it does in emotion.

- Second, if one uses the criterion of nerve connections with the hypothalamus to identify whether a structure is involved with emotion, then most of the brain would qualify as the emotional brain.

- Third, at present, only particular brain structures have been clearly indicated in emotion, in particular, the amygdale, which is involved in fear.

Thus LeDoux says that there really is no limbic system; there are clearly brain structures that are involved in emotion, and we have not yet identified all of them and their roles, but the limbic system concept is outdated.

While the limbic system concept as MacLean originally conceptualized it lacks support, it has led to some illuminating research regarding the brain and emotion. Results from neuroimaging studies (e.g., functional magnetic resonance imaging) continue to shed light on various theories of emotion processing.

In addition to the limbic system concept, other theories have focused on the role of the brain’s right hemisphere in emotion processing and the association between specific brain regions and emotions. For example, the amygdale is strongly associated with fear, the insula with disgust, and anger with the lateral orbitofrontal cortex (Murphy, Nimmo-Smith, & Lawrence, 2003).

- LeDoux, J. (1996). The emotional brain: The mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. New York: Touchstone.

- Bard, P. (1929). The central representation of the sympathetic system, as indicated by certain physiologic observations. Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry, 22, 230 – 246.

- Cannon, W.B. (1929). Bodily changes in pain, hunger, fear, and rage (2nd ed.). New York: D. Appleton.

- Herrick, C.J. (1933). The functions of the olfactory parts of the cerebral cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 19, 7 – 14.

- LeDoux, J. (1996). The emotional brain: The mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. New York: Touchstone.

- MacLean, P.D. (1949). Psychosomatic disease and the “visceral brain”: Recent development bearing on the Papez theory of emotion. Psychosomatic Medicine, 11, 338 – 353.

- MacLean, P.D. (1952). Some psychiatric implications of physiological studies on frontotemporal portion of limbic system (visceral brain). Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 4, 407 – 418.

- Murphy, F. C., Nimmo-Smith, I., & Lawrence, A.D. (2003). Functional neuroanatomy of emotions: A meta-analysis. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 3, 207 – 233.

- Papez, J.W. (1937). A proposed mechanism of emotion. Archieves of Neurology and Psychiatry, 38, 725 – 743.