Why-drivers in Reverse Logistics

Forces Driving Companies to Engage in Reverse Logistics

Graphics courtesy of Yusen LogisticsOpens in new window

Graphics courtesy of Yusen LogisticsOpens in new window

In the literature of reverse logisticsOpens in new window, many authors have pointed out driving factors like economics, environmental laws, and the environmental consciousness of consumers. Generally, one can say that companies do get involved with Reverse Logistics either

|

Accordingly, we categorize the driving forces under three main headings:

- Economics (direct and indirect);

- Legislation; and

- Corporate citizenship

- Economies

A reverse logistics program can bring direct gains to companies from dwindling the use of raw materials, from adding value with recovery, or from reducing disposal costs.

Independents have also gone into the area because of the financial opportunities offered in the dispersed market of superfluous or discarded goods and materials.

Metal scrap brokers have made fortunes by collecting metal scrap and offering it to steel works, which could reduce their production costs by mingling metal scrap with virgin materials in their process.

In the electronic industry, many products arrive at the end of useful life in a short period, but still with its components having intrinsic economic value. ReCellularOpens in new window is a US firm that has shown that it has known how to take economic advantage from this from the beginning of the nineties by trading in refurbished cell phones (Guide & Van Wassenhove, 2003).

Even with no clear or immediate expected profit, an organization can get (more) involved with Reverse Logistics because of marketing, competition, and/or strategic issues, from which are expected indirect gains. For instance, companies may get involved with recovery as a strategic step to get prepared for future legislation or even to prevent legislation.

In face of competition, a company may engage in recovery to prevent other companies from getting their technology, or to prevent them from entering the market. As Dijkhuizen (1997) reported, one of the motives of IBM’s getting involved in (parts) recovery was to avoid brokers doing it.

Recovery can also be part of an image build-up operation. For instance, CanonOpens in new window has linked the copier recycling and cartridge recycling programs to the ‘kyo-sei’ philosophy (cooperative growth), proclaiming that Canon is for “living and working together for the common good”.

Recovery can also be used to improve customer or supplier relations. One example is a tire producer who also offers customers rethreading options in order to reduce the customer’s costs. In sum, the economic driver embraces, among others, the following direct and indirect gains.

Direct gains:

|

- Legislation

Legislation refers here to any jurisdiction indicating that a company should recover its products or accept them back.

In many countries home shoppers are legally entitled to return the ordered merchandise (e.g. in the UK, consult the Office for Fair TradingOpens in new window). Furthermore, and especially in Europe, there has been an increase of environmental legislation, such as recycling quotas, packaging regulation, and manufacturing take-back responsibility.

The automobile industry and industries of electrical and electronic equipment are under special legal pressure. Sometimes companies participate ‘voluntarily’ in covenants, either to deal with or prepare for legislation.

- Corporate Citizenship

Corporate citizenshipOpens in new window concerns a set of values or principles that in this case impel a company or an organization to become responsibly engaged with reverse logisticsOpens in new window. For instance, the concern of Paul Farrow, the founder of Walden Paddlers, Inc., with “the velocity at which consumer products travel through the market to the landfill” pushed him to an innovative project of a 100-percent-recyclable kayak (Farrow and Johnson, 2000).

Nowadays indeed many firms, like ShellOpens in new window, have extensive programs on responsible corporate citizenship where both social and environmental issues become the priorities.

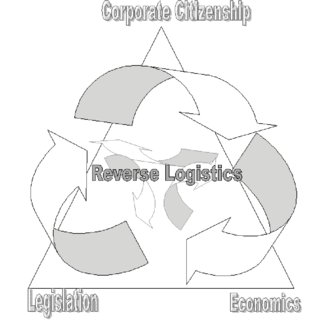

Figure X-1. Driving triangle for reverse logistics | Credit: ResearchGateOpens in new window

Figure X-1. Driving triangle for reverse logistics | Credit: ResearchGateOpens in new window

|

Figure X-1 depicts driving triangle for Reverse Logistics. One should notice that these are not mutually exclusive motivations and, in reality, it is sometimes hard to set the boundary.

In many countries, customers have the right to return products purchased via a distant seller as mail-order companies or e-tailers. Thus, these companies are legally obliged to give the customer the opportunity to send back merchandise. At the same time, this opportunity is also perceived as a way to attract customers, bringing potential benefits to the company.

The Series:

- What Is Reverse Logistics?Opens in new window

- Forces Driving Companies to Engage in Reverse Logistics (Why-drivers)Opens in new window

- Reasons for Products Being Returned in the Supply Chain(Why-reasons)Opens in new window

- Reverse Logistics Processes: How are Returns Processed?Opens in new window

- Types & Characteristics of Returned Products: What Is Being Returned? Opens in new window

- Who Are Executing Reverse Logistics Activities? Opens in new window

- Barry, J., Girard, G., Perras, C. (1993): Logistics shifts into reverse. In: Journal of European Business 5, Sept./Oct. 1993, pp. 34 – 38.

- Ayres, R. U., Ferrer, G., Leynseele, T. van (1997): Eco-efficiency, asset recovery and remanufacturing. In: European Management Journal 15, pp. 557 – 574.

- Carter, C.R., Ellram, L. M. (1998): Reverse logistics: A review of the literature and framework for future investigation. In: Journal of business logistics 19, No. 1, pp. 85 – 102.

- Elkington, J., Knight, P., Hailes, J. (1991): The green business guide. Victor Gollancz, London.

- Fleischmann, M. (2001): Quantitative models for reverse logistics. Springer, Berlin et al.

- Harrington, L. (1994): The art of reverse logistics. In: Inbound logistics 14, pp. 29 – 36.