Customer Behavior

Understanding the Consumer Buying Behavior

Graphics courtesy of Ahmed OsmanOpens in new window

Graphics courtesy of Ahmed OsmanOpens in new window

|

A significant part of a customer’s satisfaction with a product or service is determined before its consumption. It is before, and sometimes during, purchase that the customer forms expectations about the forthcoming benefits of the product or service, and thereafter its performance will always be judged against those expectations.

Anyone involved in measuring customer satisfactionOpens in new window must therefore have a detailed understanding of the ways in which customers make and evaluate their purchase decisions. These decision-making processesOpens in new window will differ between consumer and organizational markets and according to the complexity of the decision.

For customer satisfaction measurement to succeed, accurate information must also be acquired regarding the different people involved in a purchased decision. This so-called decision-making unit (DMU)Opens in new window can be quite large for some products and services in organizational markets and it is essential that the views of all DMU members are accommodated in a customer survey.

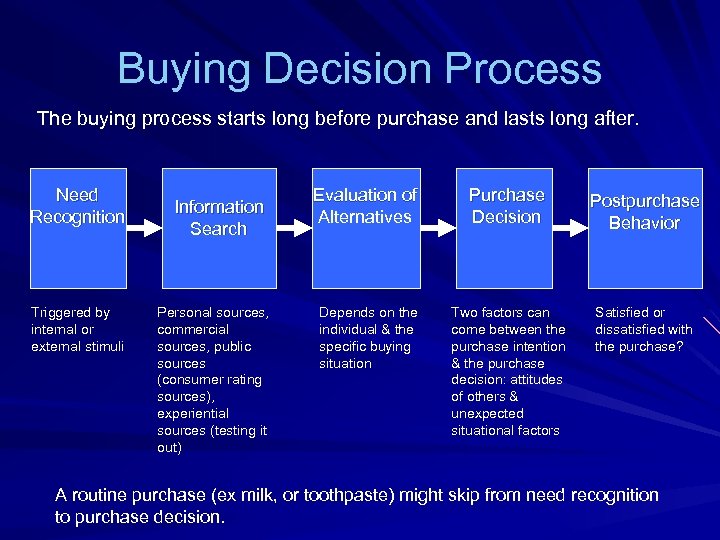

The steps an individual takes in making a buying decision may appear simple enough, but considerable activity (both mental and physical) may contribute to the process (see Figure X-1).

Figure X-1: The buying decision process of an individual

Figure X-1: The buying decision process of an individual

|

Felt (Recognized) Need

In our everyday life we constantly experience all kinds of needs: for warmth and food (biogenic needs), for the more sophisticated needs associated with job satisfaction and social status (psychogenic needs), and so on.

Before the purchase decision-making process can begin the consumer must first become aware of the existence of a need. This is sometimes called problem recognition. Once the consumer has perceived this felt need, he or she will be motivated towards its satisfaction.

A need can be aroused through internal or external stimuli – hunger pangs may originate purely internally if a long time has elapsed since eating, or they may be triggered by external stimuli such as walking past a baker’s shop.

A supplier of goods will aim to stimulate needs through means such as advertising: in the late 1970s people did not know that they needed video recorders until advertising pointed out their existence and benefits.

Once a person is aware of a need it becomes a drive, so called because he or she feels driven or urged to satisfy it. Companies and organizations must therefore understand what it is that drives a consumer to choose their particular product or service rather than that of their competitors.

Car purchase may, for example, satisfy a need for transportation, a need for status, or a need for excitement. Organizations use promotional and selling techniques to position their product or service in the market in such a way that it will appeal to potential customers.

Information Search

Once aware of a need or problem, an individual will set about solving it. Sometimes a problem is solved immediately: hunger is felt and a biscuit may be eaten. Sometimes the problem is more complex and the individual has to seek out information to help him or her solve it.

The first source of information most people turn to is memoryOpens in new window. If you need a new exhaust for your car, your first thought will almost certainly be towards the solution of this problem the last time it arose.

- Who fitted the new exhaust?

- Was it all right?

- Was the service efficient?

- Was it reasonably priced?

If your memory is favorable, that may be the end of it. You may skip the evaluation stage and make the decision to return to the same supplier as last time.

There is a major implication in this for customer satisfaction measurement. An individual’s memory is often not a particularly reliable guide to what actually happened and subjective perceptions of events are usually not overburdened with the need to conform to reality.

We often remember those things we choose to remember. In particular, we tend to remember bad, as opposed to good, experiences more vividly and for longer. But the individual customer will be quite happy with all this: his or her perception of events is reality and has to become reality for any supplier trying to sell goods or services to that individual.

Often, however, the information search will be more lengthy. You may not be entirely satisfied that the information stored in your memory is enough to enable you to make the best decision regarding your car exhaust. If this is the case, you will turn to external sources of information: you might ask for prices from two or three different suppliers.

But what if you have never had to replace an exhaust before? One answer is to consult external sources of information.

Let’s consider three such sources. You might use personal sources of information: a friend, the next door neighbor, or a relative who has experience of this kind of purchase and could give you good advice.

You might consult Yellow PagesOpens in new window or Thomsons DirectoryOpens in new window. For some products, buyers’ guides are a good source of information, as is a consumer magazine such as Which?Opens in new window These sources will provide a good comparison of alternative products.

Lastly, you might rely on commercial sources of information, which in this case would consist mainly of exhaust centers advertising in the local press. You could telephone several such centers and ask for details of their service, the kind of exhaust they fit, the duration of the guarantee offered, and the price.

A new exhaust is not a major purchase apart from the requirement for urgency which necessarily puts a time limit on the information search stage. Some products, however, represent a big step for buyers to take.

In wanting to make the right decision they may spend a considerable time at the information search stage. They will not be actively seeking information the whole time but they will be in a stage of heightened attention. In other words, they will be alert to any information concerning that felt need whether it arises in advertisements, articles or casual conversation.

Evaluation

By this time a number of alternative ways of meeting a felt need will have become evident. These alternatives must now be evaluated and this involves determining how well each option meets the felt need.

This process may be very objective, with the advantages and disadvantages of each option weighed against other alternatives; some people might even compile a list to help in their evaluation.

However objective the individual intends to be, subjective factors always influence the evaluation process to a greater or lesser extent. Three sets of subjective factors usually have an influence at the evaluation stage: beliefs, attitudes, and intentions.

- Beliefs

Beliefs are deeply entrenched views, often based on the core values of an individual’s country, sub-group (for example, ethnic group), and social class.

Although beliefs are sometimes hard to articulate they nevertheless form the foundation for much decision-making behavior. Beliefs are also, of course, social, political and religious, but for our purposes we will take a commercial example: an individual might believe that ‘branded’ products are of a higher quality than ‘own label’ products.

- Attitudes

An individual’s underlying beliefs help to form attitudes about specific events, places, products, services and such like. These attitudes are liable to change more frequently than beliefs, being strongly influenced by family, social reference groups, lifestyle, age and income.

Again thinking in commercial terms, an individual’s attitude towards particular brands of coffee might be influenced by that individual’s spending power, the type of coffee favored by his or her friends, and by the underlying belief mentioned above, that the quality of branded products is higher than that of own label products.

Therefore, the individual might hold the attitude that, for example, Gold Blend coffeeOpens in new window provides better value for money than do cheaper own label alternatives.

- Intentions

Individuals also have objectives, priorities, and aspirations that they are striving to attain, and these will often be reflected in their purchasing decisions, especially for conspicuous purchases such as cars or clothing. Thus one factor in an individual’s choice of Gold Blend coffee might be wanting visitors to know that he or she uses good coffee.

Familiarity with all three components of the customer’s evaluation process is necessary to understand customer’s satisfaction. The process also illustrates the fact that customer satisfactionOpens in new window is rarely a simple relationship between supplier and customer. An individual’s evaluation of a product or service will almost always be affected by others.

This has implications for exploratory research and for sampling – if you want to understand customer’s perceptions, rather than just identify a few quick measures of satisfaction.

Decision

Having weighed up the alternatives a decision is made. Even this decision may still be little more than an intention to purchase. Unless the buyer is in the shop handling over cash for the item or on the telephone placing an order, the purchase decision is usually a stage which precedes the purchase by some time.

Indeed, where expensive items are being considered, the decision in principle to buy and the choice of one of the alternatives could precede the actual purchase by a lengthy period, perhaps several months.

An additional factor at this stage is the level of risk the customer will associate with his or her purchase. The risk level is higher for expensive items where the buyer’s product knowledge is poor and, consequently, difficulty arises in evaluating alternatives.

Conspicuous purchases, which may affect the buyer’s credibility in the eyes of others, also tend to be associated with a high level of risk. Some individuals of course are more prone to uncertainty than others, but virtually everyone will be uncertain about some purchases.

Outcomes

Of those decision makers who do carry out their intention to purchase, some will be totally satisfied with the product and others less so. Whatever the outcome, the buyer is likely to remember this level of satisfaction and, for all but the most trivial purchases, memoryOpens in new window is likely to be influential in subsequent similar decision-making situations.

Some purchases, particularly important and expensive ones, tend to result in a great deal of subsequent reappraisal by buyers. Leon FestingerOpens in new window coined the phrase cognitive dissonanceOpens in new window to describe these second thoughts.

Doubts can be experienced by consumers when they realize that some of their unchosen alternatives also have desirable attributes; their state of heightened attention is often increased after a purchase. Promotional material will be noticed, other competing products inspected and their owners possibly questioned. It is as though buyers are trying to convince themselves that they were smart enough to have made a good decision.

In this situation it is wise for companies to do all they can to reinforce consumers’ confidence in their choice. Some advertising for inherently high-risk purchases such as cars is aimed at recent purchasers by showing satisfied buyers with their new car.

Supportive communications can also be sent through the post or reassuring telephone calls made. It is in these situations that post-transaction customer satisfaction measurement is most useful.

The possibility of cognitive dissonanceOpens in new window should always be borne in mind by those carrying out the measurement; it is particularly important to ensure swift action to resolve any customer dissatisfaction, however slight. An implication here is that post-transaction customer surveys should not be anonymous.

- Maslow A. A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review. 1943;50(4):370-396.

- Founier S. Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research. 1998;24(3):343-373.