Experimental Methods

.webp) File photo. The Developmental Stages of a Child (Online Psychology Degree Guide, 2021)

File photo. The Developmental Stages of a Child (Online Psychology Degree Guide, 2021)The majority of investigations of child behaviour and development are experimental in nature. Behaviour does not occur, and development does not take place, without a cause. |

The aim of the experimenter is to specify, in as precise a manner as possible, the causal relationship between maturation, experience and learning, and behaviour. The essential aspect of experimental techniques is control.

A situation is constructed which enables the experimenter to exert control over the causal variables that influence the behaviour of interest. One of these factors, which is called the independent variable, is varied in a systematic fashion, and objective measurements are made of any changes in the child’s behaviour.

The behaviour that is measured is called the dependent variable since (if all goes well!), changes in this behaviour are dependent upon, that is, caused by, changes in the independent variable. The following is a good example consisting in the application of the experimental method to a developmental phenomenon.

|

Why do infants grasp pictures of objects?

Judy DeLoache and her colleagues have described one of the errors that children make with objects. This is where children seem to confuse objects with pictures and may try to pick up pictures as if they were the objects they depict.

To illustrate the experimental method we will describe this effect (DeLoache et al., 1998). The famous Belgian experimental psychologist Albert Michotte (1881 – 1965) discussed the meaning of objects and the way in which a picture of an object represents the real object.

Note that adults do not confuse objects with pictures except under special viewing conditions — perhaps looking with one eye, or being given binocular stereoscopic images (these are where slightly different images are presented to the two eyes so that they give the illusion of solidity and three-dimensionality). If someone were to ask us to pick up a pictured object we’d think them very strange! However, children often think differently.

DeLoache et al. (1998) tested 9-months-old infants and their independent variable was the extent to which the objects depicted in pictures looked like the real thing. They had four versions of pictorial representations, which were, in order of realism:

- a highly realistic coloured photograph of real objects (such as a toy car);

- a black-and-white photograph;

- a coloured line drawing of the object; and

- a black-and-white line drawing.

Figure X-1 An example of a 3D toy car (top left) and three 2D representations of the car.

Figure X-1 An example of a 3D toy car (top left) and three 2D representations of the car.Source: Dr. Sophia Pierroutsakos, reproduced with permission. |

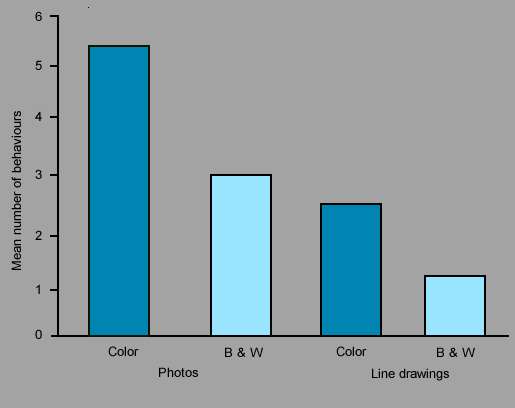

All of the depicted objects measured approximately 3 cm x 3 cm, a size that matches the size of the infants’ grasp. An illustration of these is given in Figure X-1. Their dependent variable was the amount of manual investigation of the depicted objects, which included attempts at grasping them. The results are shown in Figure X-2 and clearly show that the closer the depicted object is to the real object, the greater the amount of manual exploration. Sometimes the pictured object is just too enticing!

Figure X-2 Grasping and reaching behaviours were clearly related to how realistic the pictures were; the more pictures looked like the real object, the more exploration they evoked.

Figure X-2 Grasping and reaching behaviours were clearly related to how realistic the pictures were; the more pictures looked like the real object, the more exploration they evoked. |

Deloache et al. had other experimental conditions. Their 1998 paper describes two experimental findings: a cross-cultural comparison — 9-month-old infants from two extremely different societies (the United States and the West African republic of the Ivory Coast) produced the same reaching and grasping behaviour; a cross-sectional study, where different infants were tested at three different ages (9, 15 and 19 months) — the younger infants reached and grasped, by 15 months this behaviour was rare, and by 19 months of age they merely pointed at the pictures.

Note that in this instance the independent variable is the age of the infants. In a further experimental condition 9-months-olds were presented with the realistic picture and the real object — in this condition none of the infants reached for the picture! Presumably, under these conditions the real object was clearly seen to be more realistic and graspable than the picture.

Deloache et al. interpret their intriguing results as indicating that the younger, 9-month-olds, do not understand the ways in which depicted objects are both similar to and different from real objects: when the real object is not present they treat the pictures as if they were real objects because in many wasy they look like real objects.

As they gain experience the infants develop a more sophisticated understanding of the relationship between the pictures and the objects they depict, and learn that pictures are representations of objects.

Structured observation is an observational study in which the independent variable is systematically controlled and varied, and the investigator then observes the child’s behaviour. Similar to an experiment but the degree of control is less precise than in a laboratory setting.

Deloache et al. are able to tell a convincing developmental story of the nature and development of infants’ understinading of pictures and objects.

In these experiments the independent variables — such as the realism of the pictorial representations and the age of the infants — were systematically varied, and the experimenters then carefully observed the babies’ reaching responses.

Sometimes this sort of experiment is called a structured observation, and there are those who would distinguish between this sort of experiment and those involving more formal or precise measures of the dependent variable. There is clearly an element of observation in many, perhaps most, experimental studies of children’s development.